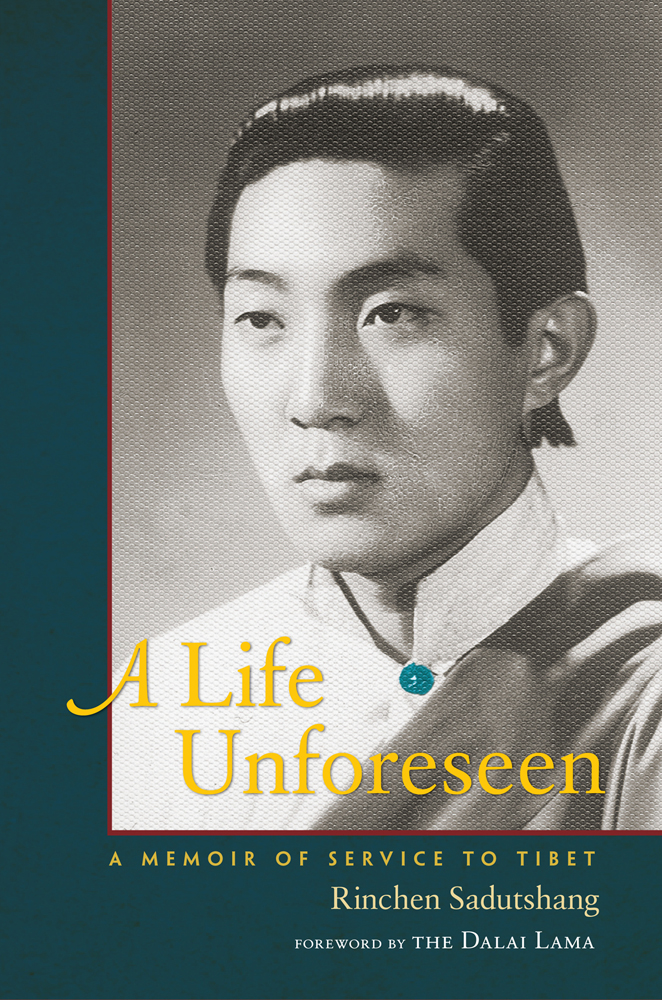

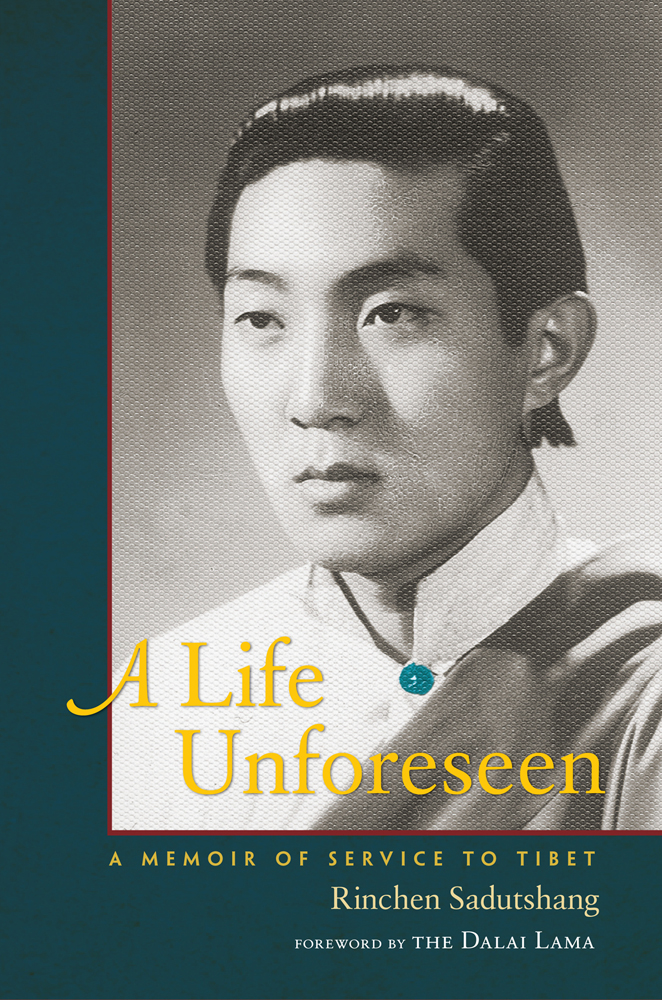

A LIFE UNFORESEEN

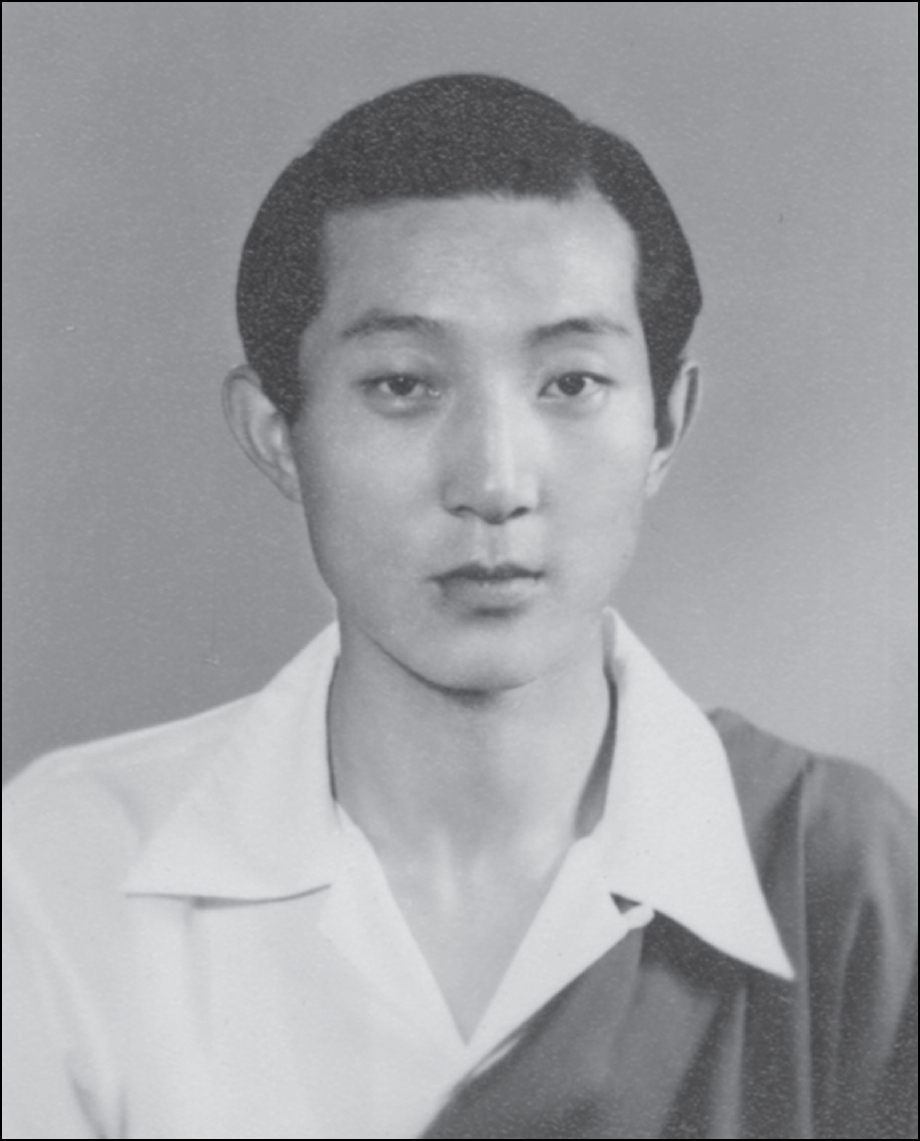

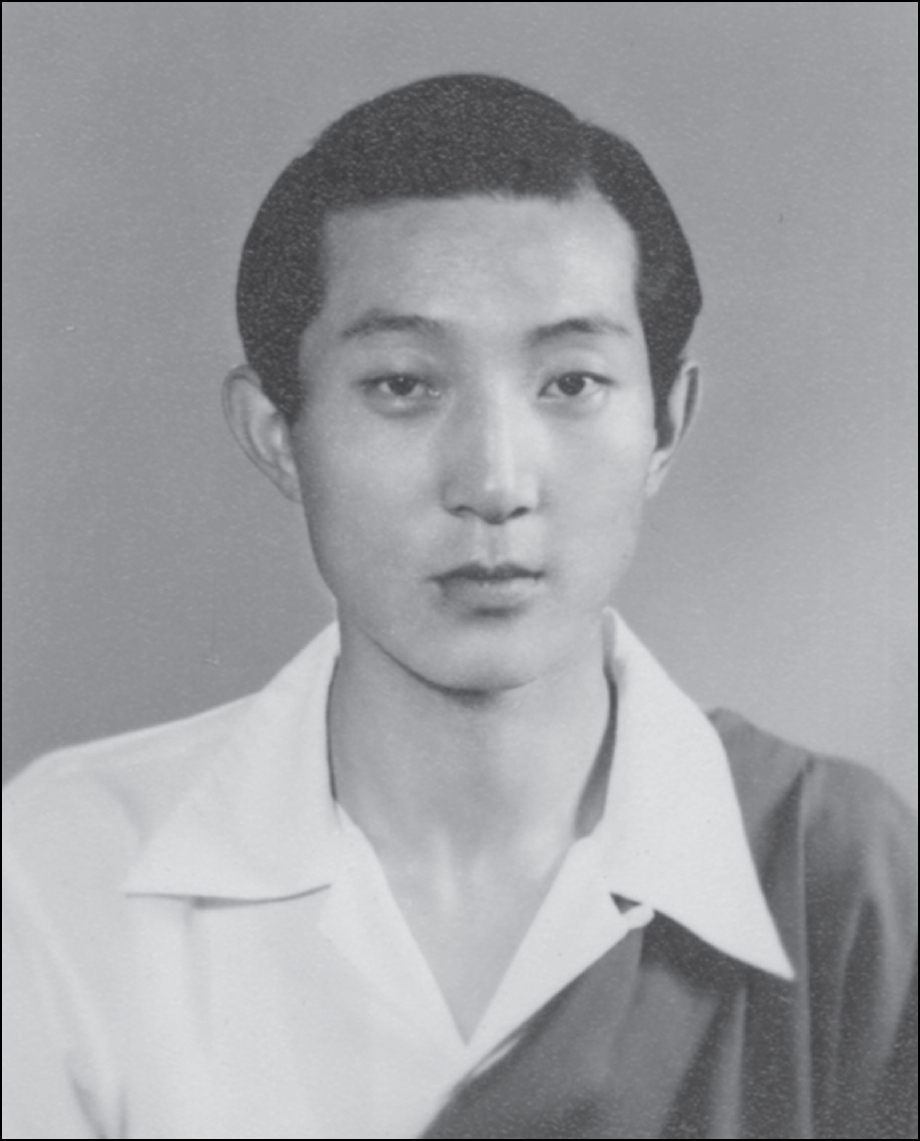

The author as he appeared on his travel certificate, 1959.

A government official in pre-Communist Tibet recounts the pivotal events that changed his homeland and the fate of his people forever.

I am pleased Rinchen Sadutshang has seen fit to record events as he saw them. Perhaps because he began his career at such a young age, his memories are particularly clear and closely observed. I commend this book, confident that it sheds light on critical events in recent Tibetan history.

His Holiness The Dalai Lama, from his foreword

R INCHEN SADUTSHANG was born in 1928 near the Tibet-China border and served in the Dalai Lamas government both before and after the 1959 Communist takeover. A refugee alongside tens of thousands of his countrymen, but one of very few who spoke English, he played a crucial role in bringing the plight of the Tibetan people to the worlds attention.

In this memoir Sadutshang recounts his long, fascinating career in service to the Tibetan cause, including a firsthand account of the Dalai Lamas historic meeting with Chairman Mao. From meeting British viceroys and Chinese generals to successfully pleading Tibets case before the United Nations, he offers a firsthand perspective on extraordinary historical events. Sadutshang passed away in July of 2015.

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

R inchen Sadutshang is one of the few Tibetans of his generation to have had the opportunity to learn English and receive a modern education during the late 1930s and 1940s, a time when Tibetans urgently needed to understand the workings of the world beyond their borders.

Enrolled in Tibetan government service in 1948, he worked with dedication and was present on several occasions that proved crucial to Tibets eventual destiny. He accompanied the Tibetan delegation to Beijing in 1951, when the Seventeen-Point Agreement was signed. Later, he was a member of the Tibetan delegations to the United Nations in 1959 and 1961. In between, he was a member of the party that accompanied me when I visited China in 1954 and India in 1956. All of these events he describes here with characteristic candor and acute observation.

In exile, he worked assiduously for the Tibetan cause, serving the Central Tibetan Administration in various capacities, becoming a Kalon minister and ultimately our representative in New Delhi.

I have frequently encouraged Tibetans who have lived through the last sixty years or so and have taken part in this most difficult period of Tibetan history to write their memoirs so that Tibetans who have been born since 1959 and other interested people should have access to their recollections. I am pleased Rinchen Sadutshang has seen fit to record events as he saw them. Perhaps because he began his career at such a young age, his memories are particularly clear and closely observed. I commend this book, confident that it sheds light on critical events in recent Tibetan history.

Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

PREFACE

In happier circumstances my father, Rinchen Sadutshang, would have written this preface himself. Unfortunately, he passed away on June 14, 2015, at the age of eighty-seven, before the final publication of his book. Since I had been assisting him with the process, the responsibility has fallen to me, his daughter.

My father bore firsthand witness to the defining moments of Tibets modern history. As a government official, he saw up close the entire course of events that led to the takeover of Tibet by the Chinese Communist government from the failed attempts of the Tibetan government to elicit the help of foreign powers to deter the Chinese incursion, to its desperate attempts later to safeguard Tibets sovereignty during negotiations with the same aggressor when confronted with the threat of complete occupation, thinly veiled as liberation by the Chinese. This, as well as the Dalai Lamas exhortations to older Tibetans born in a free Tibet to record accounts of their lives both in Tibet and in exile thereafter for the sake of future generations, moved him to compose this autobiography.

In the typical self-effacing Tibetan way, Rinchen Sadutshang hardly admits to having made any valuable contribution, but his service to the Tibetan government and to the Tibetan people should not be downplayed. One only needs to read this book to see why. In many instances he was the person most suited to fulfill a given assignment, for he had certain advantages over other officials of that period.

At a time when literally only a handful of Tibetans in Tibet spoke English or had a modern education, Rinchen Sadutshang was blessed with both. In Tibet he was able to use this asset to the benefit of his country by being employed at the foreign ministry and by serving as an interpreter for senior officials during talks with foreign governments. Later, when the Dalai Lama sought asylum in India, Rinchen Sadutshangs role became even more vital, for suddenly, virtually the entire government in exile was faced with the enormous problem of inability to communicate with Indian officials compounded by its unfamiliarity with India itself. Hence, he proved indispensable at the Dalai Lamas private secretariat when it first opened in India. He was also invaluable when the government in exile sought to embark on a most important mission in the early 1960s, that of sending a delegation to the United Nations, which it did three times. In much the same way, he was highly suited for his last appointment as representative of the Dalai Lama at His Holinesss bureau in New Delhi, as this required sensitive communication with embassies and foreign organizations. His predecessor, though well versed in Tibetan, did not have a modern education and could not speak English.

Having been raised in a family that earned its living through trade, Rinchen Sadutshang undoubtedly knew a thing or two about business, unlike most other Tibetan officials of the time, who were born aristocrats and lived on the proceeds of their estates. Therefore it was no surprise that the Tibetan government saw him as an obvious choice when it appointed him a trustee of the Dalai Lamas Charitable Trust, for the trust dealt with the management of money derived from the sale of the Tibetan government gold and silver brought over to India from Tibet in the 1950s. Likewise, he was persuaded to work for Gayday Iron and Steel Company, an ongoing business enterprise in which the Tibetan government had investments, though being astute, he could see from the start that this enterprise was ill fated. His years in the company were fraught and stressful because of the constant problems the company faced, which he details here. At the time, bureaucrats in Dharamsala, the seat of the exile government, simply had no idea of the hurdles he faced, since they knew very little about running a company. He acquired a great deal of experience on the job and, being intelligent, quickly became familiar with corporate law, the running of an industry, and the norms of banking.

Next page