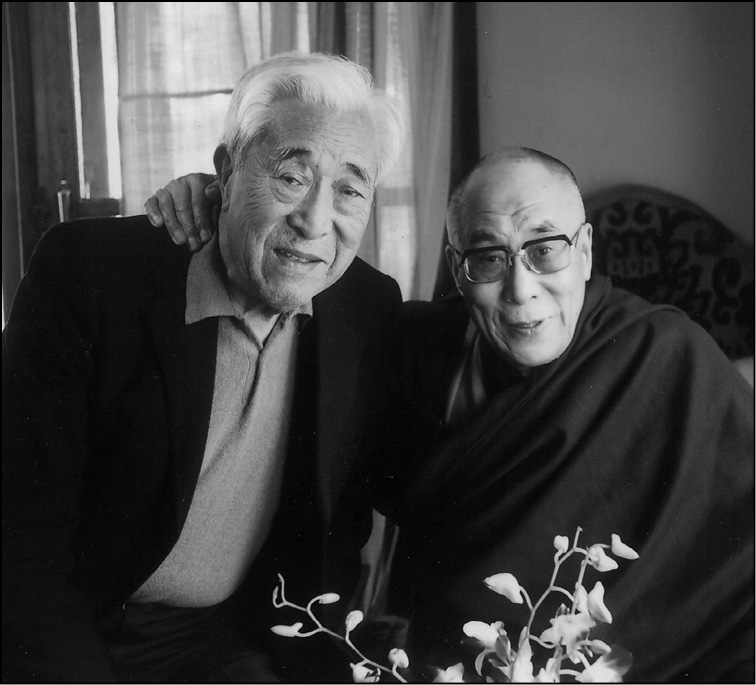

Gyalo Thondup (left) and his brother the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, 2011 in Kalimpong

Copyright 2015 by Gyalo Thondup and Anne F. Thurston.

Photos, unless otherwise noted, used by permission of

Gyalo Thondup and Tanpa Thondup.

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs,

a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107. PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 8104145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special.markets@perseusbooks.com.

Book Design by Cynthia Young

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rgya-lo-don-grub, Lha-sras, 1928

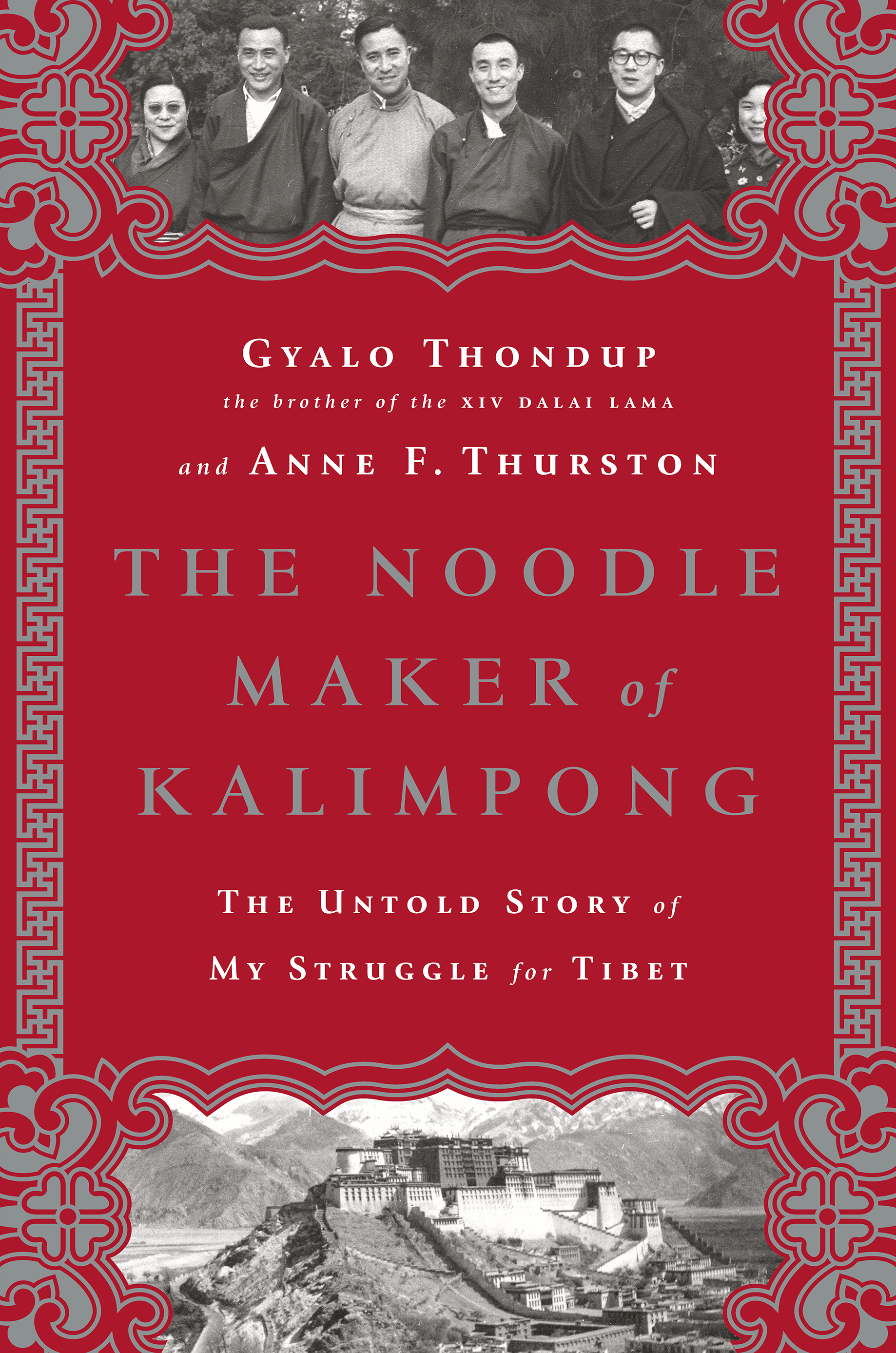

The noodle maker of Kalimpong : the Dalai Lamas brother and his struggle for Tibet / Gyalo Thondup, elder brother of the 14th Dalai Lama and Anne F. Thurston, coauthor of The Private Life of Chairman Mao.First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61039-290-7 (ebook)

1. Rgya-lo-don-grub, Lha-sras, 1928 2. PoliticiansChinaTibetBiography. 3. Bstan-dzin-rgya-mtsho, Dalai Lama XIV, 1935Family. 4. Central Tibetan Administration-in-Exile (India)Officials and employeesBiography. 5. Tibet Autonomous Region (China)Politics and government. 6. Tibet Autonomous Region (China)Biography. 7. TibetansIndiaBiography. 8. Kalimpong (India)Biography. I. Thurston, Anne F. II. Title. III. Title: Dalai Lamas brother and his struggle for Tibet.

DS785.R44 2015

951.505092dc23

[B]

2014046680

FIRST EDITION

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama.

For the people of Tibet,

to those who have fought for our freedom,

and in memory of those who sacrificed their lives for the cause.

Table of Contents

Writing The Noodle Maker of Kalimpong

The Fourteenth Dalai Lama and his brother Gyalo Thondup could scarcely be more different. But the ties that bind them are unbreakable. They are two sides of the same struggle for the survival of Tibet. In the politics of modern Tibet, only the Dalai Lama himself has been more important than Gyalo Thondup.

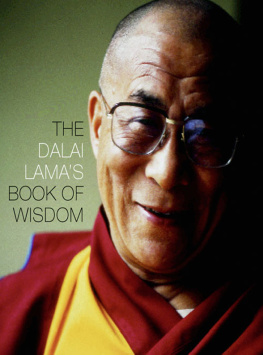

The Dalai Lama is the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhists and of Buddhist believers everywhere. He has won the respect, admiration, and even adulation of a worldwide audience. My message is always the same, writes the Dalai Lama, to cultivate and practice love, tenderness, compassion and tolerance.

Gyalo Thondup sees himself as an obedient, selfless, and loyal servant to the Dalai Lama and Tibet. But his work has been conducted in secret, out of the limelight, in the nitty-gritty of international politics and the violence of a clandestine war of resistance.

Of the five male siblings who lived to adulthood, Gyalo Thondup alone did not become a monk. Instead, from the time the family moved to Lhasa in 1939, just after his brother Lhamo Thondup had been annointed the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, he was groomed to serve his brother on matters of state. Reting Regent, who had been chosen to serve as head of state until the young Dalai Lama reached majority, considered relations with China to be of such immense importance and Tibetans knowledge of their giant neighbor so weak that Gyalo Thondup was sent to study in China. President Chiang Kai-shek was to become his sponsor.

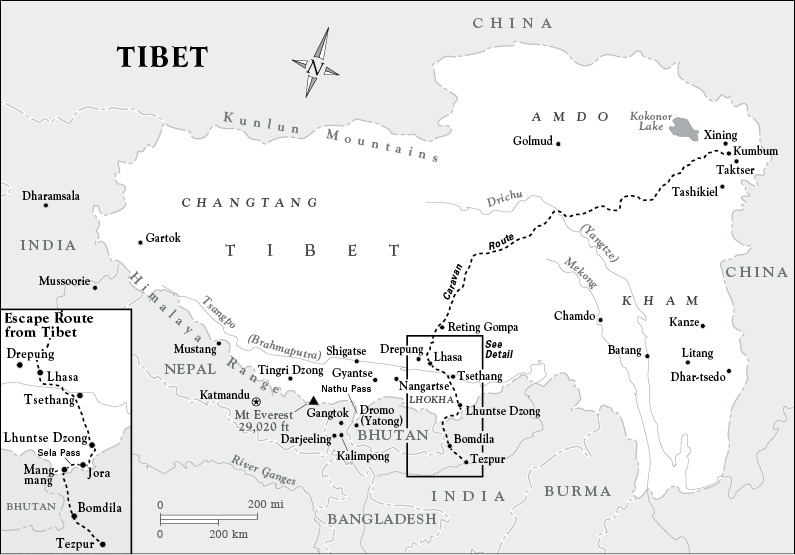

When Chiang Kai-shek and his Nationalist Party lost the long civil war to Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party, Chinas long latent threat to Tibet quickly turned real. The Tibetan government was forced under duress to sign the Seventeen Point Agreement ceding sovereignty to the recently established government of mainland China. As parts of Tibet rose up in resistance against their new rulers, Gyalo Thondup, then in exile in India, became the secret interlocutor between the CIA and the underground freedom movement in Tibet. His efforts helped keep the resistance movement alive. When the Dalai Lama was forced to flee his homeland in March 1959, Gyalo Thondup was at the border just inside India to greet him, having obtained from Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru a grant of political asylum for his brother and everyone who had accompanied him in flight.

With the Dalai Lama safely in India, Gyalo Thondup became a leading figure within the new Tibetan government-in-exile, serving as the major spokesman for Tibet to the Indian government and most of the outside world, including the United States and the United Nations. A rarity among Tibetans, Gyalo Thondup is fluent in Tibetan, Chinese, and English, allowing him to communicate directly with many of the worlds most powerful leaders. In 1979, after the death of Mao Zedong and the ascension to power of Deng Xiaoping, it was to Gyalo Thondup that the new Chinese leader turned to re-establish contact with the Dalai Lama and the Tibetans in exile. For more than two decades, Gyalo Thondup shuttled between India and China trying without success to negotiate an agreement that would allow the Dalai Lama to return to his homeland.

For years, people close to Gyalo Thondup have encouraged him to write his memoirs, and for years he has promised that he would. Representatives of the Chinese Communist government even offered to send him to an island resort with a team of journalists to help put the story together. Gyalo Thondup called upon his friend Elsie Walker instead, hoping she could find someone, an American perhaps, to help him write.

Elsie Walkers friendship with the Dalai Lama traces back for decades, and so, too, does her friendship with several members of his family, including Gyalo Thondup. Elsie had been instrumental in arranging the Dalai Lamas first meeting with an American president, her cousin George H. W. Bush, and later made the introductions that led to the ongoing friendship between His Holiness and the second President Bush. She had worked inside Tibet for years, cooperating with local officials on grassroots development projects. Elsie turned to me in the hope that I might help. She had read The Private Life of Chairman Mao that I wrote with Maos longtime personal physician, Li Zhisui, and knew that I had experience interviewing.

When Elsie Walker broached the possibility of my working with Gyalo Thondup, I was fascinated. But I demurred. I was too busy. I was not a Tibet specialist. I am a student of modern and contemporary China. Elsie saw my China background as a plus. China looms so large in the life of contemporary Tibet that understanding what is happening in Tibet requires an understanding of China, too.

We found another China specialist, a young journalist who had once been a student of mine, to write the memoirs. But when the possibility of retaliation from the Chinese government proved too daunting, he had to pull out of the project. By then, even after 35 years of visiting China, living there for a number of them, being devoted to understanding China and promoting better cooperation between our two countries, and writing several books, the Chinese government had refused my request for a visa. China had been my lifes work and my passion, and suddenly I was no longer allowed to go. But I could not stop writing. Gyalo Thondup gave me a new story to tell.