About the Author

Andrew M. Fischer is associate professor of social policy and development studies at the Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in The Hague, Netherlands (part of Erasmus University Rotterdam since 2009). He is also convener of the MA major in Social Policy for Development at ISS, in which he leads teaching on poverty studies, population, social policy, inclusive development, and development economics. A development economist by training and an interdisciplinary social scientist by conviction, he has been involved in researching or working in development studies or in developing countries for over twenty-five years and on Chinas regional development strategies in the Tibetan areas of Western China for more than twelve years. Beyond his work on Tibet, he deals more generally with inclusive development strategies to combat poverty, inequality, and social exclusion. A major focus of his current research is centred on the imperative and challenges of redistribution in contemporary development. He has published widely on subjects related to Chinas development and on the international development agenda more generally. He earned a PhD in Development Studies from the London School of Economics and an MA in Economics from McGill University in Montreal, Canada.

Acknowledgments

I am always uncomfortable writing an acknowledgment for work on the politically sensitive region of Tibet, particularly on matters that are politically sensitive, because those to whom I am most indebted invariably cannot be mentioned. Doing so would risk complicating their lives, especially since the widespread protests of 2008 and, again, since the recent protests centerd on the wave of self-immolations that started in 2011 and continue at the time of writing. Suffice it to say that if and when they would ever read this text, they would know who they are. I extend my deepest gratitude to them, in particular the numerous Tibetans, Chinese, Chinese Muslims, Mongolians, and Mongours whom I met in the course of my fieldwork, including scholars, development workers, officials, monks and nuns, lamas, teachers, students, farmers, pastoralists, businesspeople, workers, and unemployed. Special mention goes to the numerous refugees, from all regions of Tibet, with whom I had intimate contact during my time living in India and Nepal from 1995 to 2001. They provided me with many initial insights into the state of marginalization faced by Tibetans in the Tibetan regions of China. They also fueled my initial inspiration to return to the world of academic research, after escaping it in youthful disillusion for about ten years.

Among those who can be named, many deserve to be mentioned. These include, in alphabetical order: Andre Alexander, Anders Anderson, Bob Ankerson, Robbie Barnett, Ken Bauer, Beimatso, Andrew Bunbury, Geoff Childs, Sue Costello and her family, Sienna Craig, Thierry Dodin, Philippe Dufourg, David Germano, Mark Giffard-Lindsay, Ethan Goldings, Melvyn Goldstein, Nancy Harris, Arthur Holcombe, Charlotte Hyvernaud, Iida, Erika Jacobson, Tanzen Lhundup, Li Tao, Gelek Lobsang, Ma Cheng Jun, Anna Morcom, Franoise Robin, Ma Rong, Damien Morgan, Padmatso, Fernanda Pirie, Losang Rabgey, Tashi Rabgey, Carol Sandup, Kate Saunders, Kevin Stuart and his team of teachers and students in Xining, Lobsang Tashi, Gray Tuttle, Daniel Winkler, Yang Wenkui and family, Yangzhongtar, Emily Yeh, Yi Lin, and Yi Qing. I would also like to thank Adrian Zenz, whom I discovered at the last minute of finalizing this book when I was asked to review his book by editors at Brill. Finally, Mary Zsamboky is beyond thanking; words do not suffice for the immense inspiration and help that she brought to the waning moments of this book project.

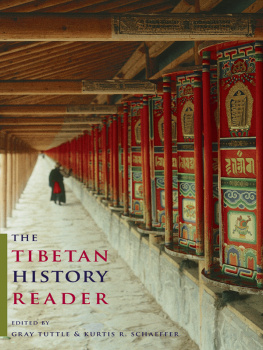

Special thanks go to Gray Tuttle, the editor of this series published by Lexington. He approached me to publish in the series in 2007, before the events of 2008, and he has since been incredibly patient and encouraging with my perpetual delays in finishing the book. I could not imagine a more supportive series editor and I hope that I have done justice to his trust and confidence. Great thanks are also due to the anonymous reviewers of the book, as well as to Emily Yeh for her invaluable input, comments and suggestions, despite living and working in one of the few nations left on earth than does not have any meaningful maternity leave. The editors at Rowman & Littlefield have also shown much patience since first negotiating the book contract with me in 2007, particularly given that the preparation of this book has passed through at least three of them, to the best of my knowledge, each of whom has been very helpful: Patrick Dillon, Justin Race, and Sabah Ghulamali. The most patience was shown by Justin Race and the most work has been done by Sabah Ghulamali, who took over the book just as we were starting to enter into the production phase. Thanks also to Laura Reiter, the production editor of the book, whose helpfulnes and effectiveness have impressed me.

Much of the research of this book was conducted during my PhD studies at the London School of Economics from 2002 to 2007, and several people from this period deserve special thanks. Athar Hussain and Stephen Feuchtwang both served as my supervisors in the first year of my PhD, Athar formally and Stephen informally. James Putzel took over from Tim Allen as my supervisor at the Development Studies Institute at LSE in my second year and was an exemplary guide and has been an incredible source of support and friendship ever since. Tim Dyson, Jo Beall, and John Harriss also provided enthusiastic support throughout the course of my years at LSE. Finally, I would like to thank my two PhD thesis examiners, Peter Townsend and Sarah Cook, whose meticulous examination of my thesis improved it immensely.

I continue to be guided by the inspiration of several of my early academic teachers from McGill University in Montreal, namely, the late Tom Asimakopoulos, Tom Kompas, Tom Naylor, Kari Polanyi-Levitt, Charles Taylor, and James Tully. I also pay my respect and devotion to my spiritual teachers, in particular the trinity of my root gurus: His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Thubten Zopa Rimpoche, and the late Khalkha Jetsun Dhampa Rimpoche, whom I had the great fortune of serving for three years.

Several generous contributions made the early phases of this research possible. These deserve mentioning, even though I have had no financial support since 2006 (besides my own research funds provided by my current institute, the Institute of Social Studies in the Hague, the Netherlands, part of Erasmus University Rotterdam since 2009). These include: The Qubec Government (Fonds qubecois de la recherche sur la socit et la culture), the UK Government (Overseas Research Student Award), the London School of Economics, and the Canadian Section of Amnesty International, all of whom provided general PhD funding. In addition, the Crisis States Research Centre at the LSE and the Central Research Fund of the University of London provided field research funding in 2003 and 2004. More recently, my staff group in my current place of workthe Institute of Social Studiescontributed some of the typesetting costs during the final stage of producing this book.

However, this journey would never have left the ground had it not been for the vital assistance of my mother, Phyllis Fischer, at the start of my degree, when I had been left financially stranded by all other funding sources. Without her support, I would probably be working in an INGO right now rather than pontificating in academia. While I am still not sure whether the latter will end out being more beneficial to society, her faith in me never ceases to amaze me, just as her commitment to social justice has never ceased to awe me. I hope to repay her by living in her example.

Many people have contributed to this book. Whatever merit is contained within is surely in large part the result of their collective wisdom. The opinions expressed are my own, and any erroneous meanderings are due entirely to my own ignorance or arrogance, having not listened enough to those who know better.