Contents

We Uyghurs Have No Say

We Uyghurs Have No Say

An Imprisoned Writer Speaks

Ilham Tohti

Translated by Yaxue Cao, Cindy Carter,

and Matthew Robertson

The editors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of China Change

(https://chinachange.org/) in preparing this book.

First published by Verso 2022

Collection Verso Books 2022

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors and translators have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-404-2

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-405-9 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-406-6 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Sabon by Biblichor Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

Today Ilham Tohti sits in a Chinese prison, where he is serving a life sentence for the content of his writings. Seven of his students are imprisoned for participating in his intellectual project. Reading through his essays and interviews now, with hindsight, is both illuminating and heartbreaking. Ilham was right, even prescient. He was right that he would be imprisoned, that, in one way or another, the grim reaper is beckoning. And he was right about the danger that totalitarian ethnonationalists in the Chinese Communist Party posed to indigenous groups under their rule, especially Ilhams own people, the Uyghurs.

It turns out that some of Ilhams most dire warnings were understated. From 2017 to 2019, somewhere around 10 percent of the Uyghurs in China, perhaps 1 million people or more, disappeared into what the Chinese government at first called concentrated transformation education centers and then renamed vocational training centers. The Washington Post and other sober observers call them concentration camps. In them, Uyghurs have been forced to abandon their language and traditions, renounce their religion, and memorize Party ideology. More recently, many have been transferred to formal prisons or forced labor programs.

Uyghurs outside the prisons and camps experience a different kind of confinement. They are tracked through both elaborate electronic surveillance and old-fashioned totalitarian legwork. Mandatory spyware apps, cameras with facial recognition capabilities, GPS trackers on cars, and predictive policing software bring nearly every movement and utterance under the gaze of the state. To catch what little slips through the electronic net, over 1 million Chinese people of the majority Han ethnic group have been sent to become family with Uyghurs, entering rural homes, interviewing their residents, reporting on their habits, and, in many cases, sleeping in their beds. A regional government newspaper, summing up the successes of 2018, boasted of over 10 million overnight becoming family stays. In some cases, Han Chinese visitors literally become family, as young men marry Uyghur women in an environment where saying no is almost impossible.

The disciplinary measures undergird more direct efforts to destroy the Uyghurs as a group. Children are forcibly separated from their parents and educated in Chinese language and culture. By 2019, roughly half of Xinjiangs middle-school-aged children were placed in compulsory residential schools, with the explicit intent to isolate minority children from the cultural influences of their families. At the same time, an unprecedented program of forced birth control and sterilization has brought the Uyghurs population growth to nearly zero, all while the state encourages Han parents to have more children.

Ilham, in his prison cell, is almost entirely cut off from the outside world and may not yet be aware of the full scale of the program that has swept up not only his fellow Uyghurs, but also Kazakhs, Kirghiz, and some Hui. The essays collected here, written before Ilhams 2014 arrest, do not address the very latest injustices but instead analyze the economic, political, and discursive structures that were already squeezing Uyghurs when Ilham began publishing in the 1990s. His work is a reminder that todays internment camps are merely the crescendo of a longer, deeper, and more entrenched dispossession of the Uyghurs.

But Ilhams work is not just relevant to the problems of the Uyghurs, or even of minorities in China more generally. It offers a distinctive perspective on global phenomena of marginalization, a perspective honed outside the boundaries of Western-dominated academic conversations like post-colonial studies and the sociology of race. To give one example, his description of minoritized groups as social blank spacean open field in which social experiments can be conducted at will is at once a fresh response to the Chinese context and immediately recognizable in the global history of colonization and subjugation.

The nuances of Ilhams contributions at both levelsexplaining the development of Chinas current cultural cleansing program and broadening our understanding of marginalization at a global scaleare perhaps best appreciated alongside a basic introduction to their context. This is because, on the one hand, the Uyghurs and other minorities of the Peoples Republic of China (PRC) are unfamiliar to many readers, and, on the other hand, all of Ilhams writing to date has been undertaken in highly constrained circumstances, in which each word choice was a danger to Ilham and his friends and family. Much was left unsaid and many apparently small gestures have enormous import. For these reasons, I offer here some basic introductory remarks about the Uyghurs and their relationship to China, along with notes on Ilham himself and his relationship to the current Chinese government.

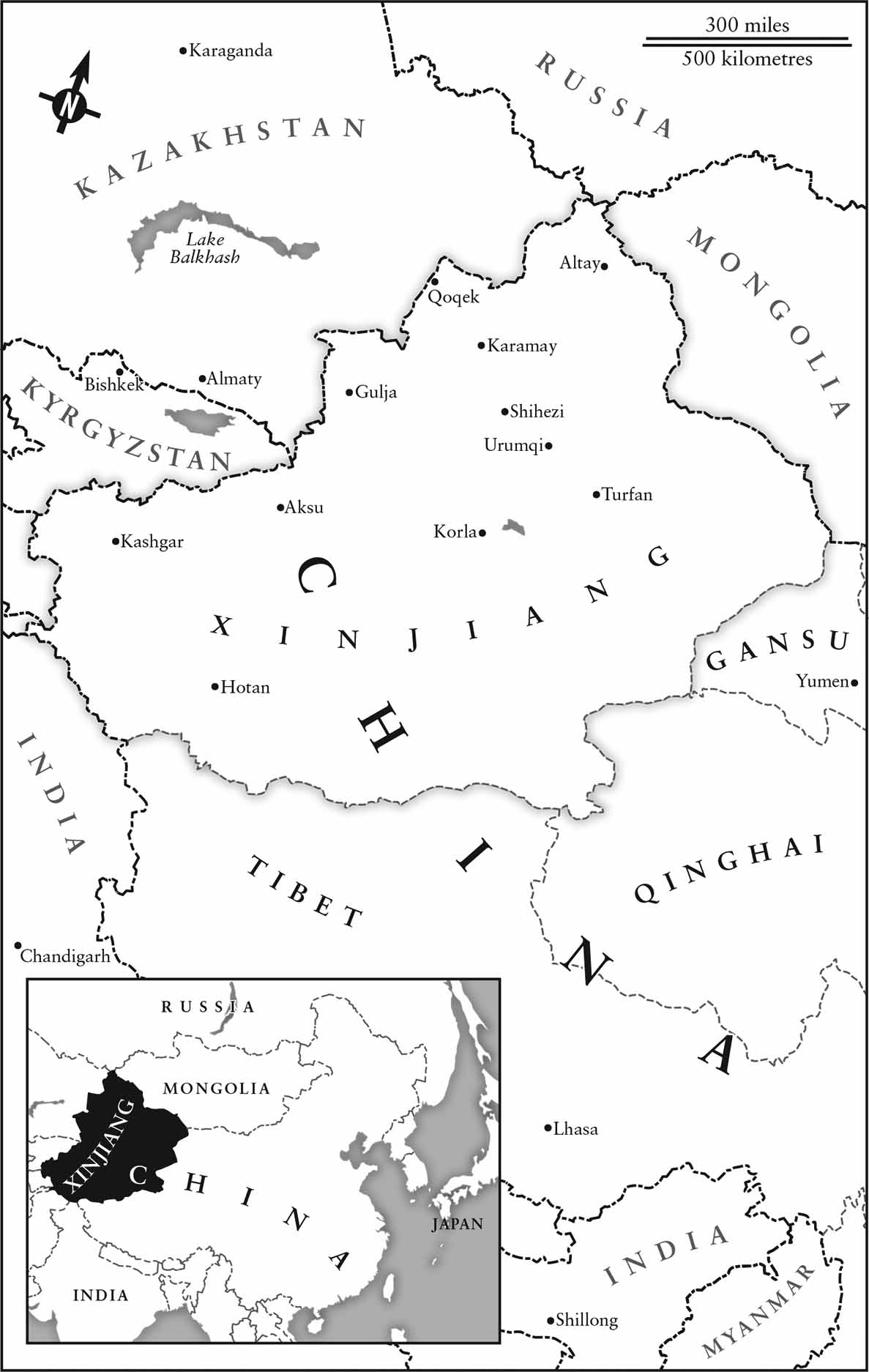

The Uyghurs and China

Ilham is a member of the Uyghur ethnic group, a people whose Turkic language, Central Asian traditions, Islamic heritage, and, in most cases, physical features set them apart from Chinas largest ethnic group, the Han. The Uyghur homeland has been known by various names over the centuriesXiyu, Moghulistan, Altishahr, Kashgaria, Little Bukharia, Eastern Turkestanbut today it falls within the borders of Chinas Xinjiang administrative unit. This name, officially bestowed on the region in the late 1800s, gives a hint of how the Uyghurs came under Chinese rule; it is a Chinese word for new territory.

When Chinas last imperial dynasty, the Qing, fell to revolutionaries in 1912, intellectuals and politicians trying to build a new Chinese order faced a conundrum. One important source of support for the revolution had been the ethnonationalist idea that the Qing rulers, who were Manchus rather than Chinese, were outsidersbarbarian conquerors prone to mis-rule. But the Manchus had not only conquered Chinese-inhabited lands. They had also conquered Tibet, Mongolia, and the part of Turkestan they renamed Xinjiang. What should the Chinese leaders who took control of the Qing state do with this imperial inheritance?

The question was particularly fraught because many Chinese thinkers saw themselves as opponents of imperialism: Manchu, Japanese, and European. Some argued that their new Republic of China should release the other conquered regions. They lost the argument to Sun Yat-sen and others, who redefined China to encompass everything the Manchu Qing emperors had controlled, and the Chinese as anyone within these borders.