BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Party

Richard McGregor

ASIAS RECKONING

The Struggle for Global Dominance

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in the United States of America by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC 2017

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2017

Copyright Richard McGregor, 2017

Photograph credits

Insert : Getty Images / AFP / Kimimasa Mayama

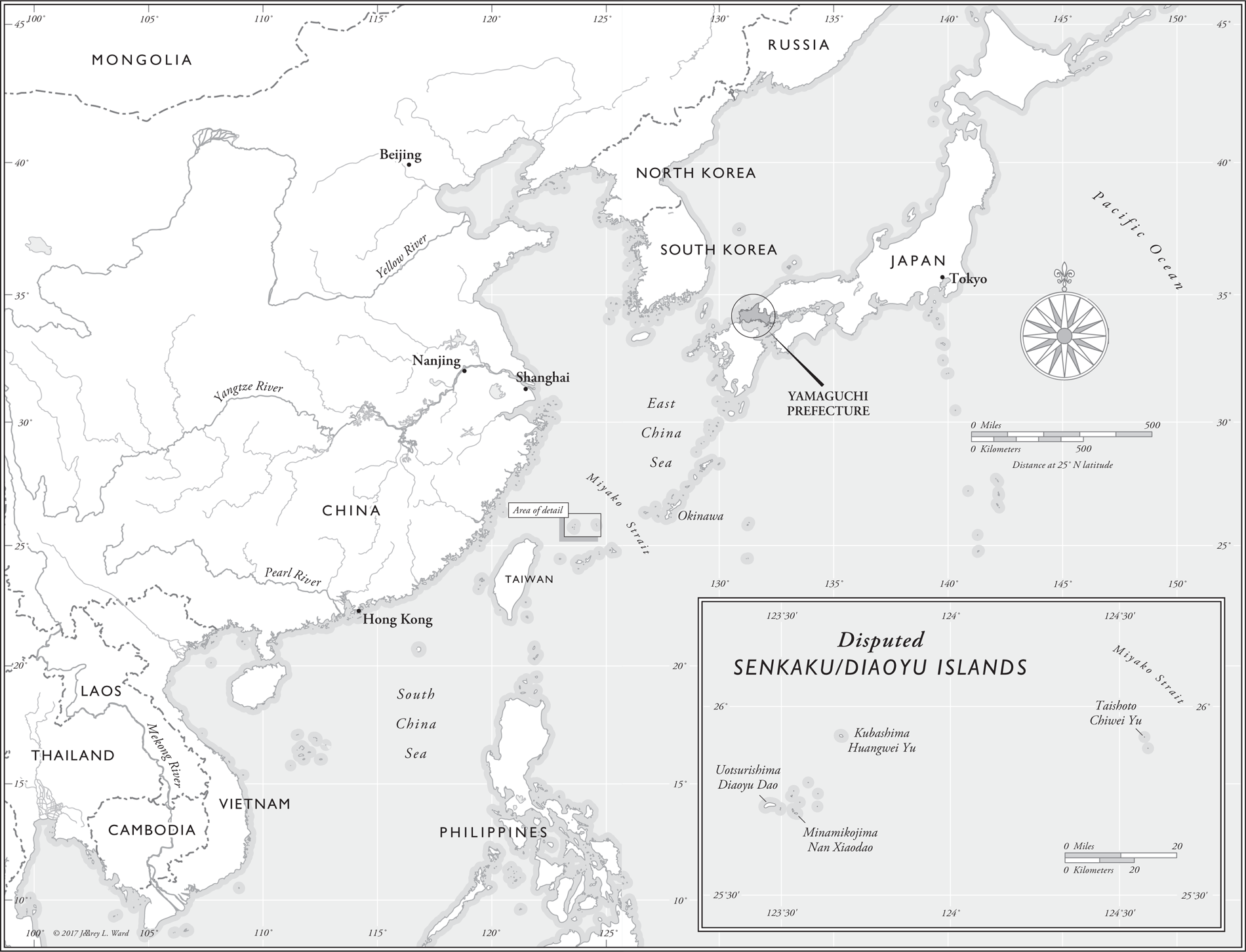

Map illustration by Jeffrey L. Ward

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover design: Jim Stoddart

ISBN: 978-0-241-25015-0

To Kath, Angus, and Cate

Preface

There is no shortage of scenarios in which Americas postwar world comes under challenge and starts to crack. It could take the form of a draining showdown with Islamist radicals in the Middle East, a conflict with Russia that engulfs Europe, or a one-on-one superpower naval battle with China. Soon after his election, Donald Trump finished his first conversation as president-elect with Barack Obama at the White House fretting about the threat from a nuclear-armed North Korea.

In daily headlines, the jousting between China and Japan cant compete with the medieval violence of ISIS or the outsize antics of Vladimir Putin or threats from tyrants like Kim Jong Un. The rivalry between the two countries has festered, by some measures, for centuries, giving it a quality that lets it slip on and off the radar. After all, China and Japan, according to the conventional wisdom, are at their core practical nations with pragmatic leaders.

The two countries, along with Taiwan, South Korea, and Southeast Asia, sit at the heart of the global economy. The iPhones, personal computers, and flat-screen televisions in electronic shops around the world; most of the mass-produced furniture and large amounts of the cheap clothing that fill shopping centers in the United States, Europe, and the United Kingdom; a vast array of industrial goods that consumers are scarcely aware of, from wires and valves to machine parts and the likeall of them, one way or another, are sourced through the supply chains anchored by Asias two giants. With so much at stake, how could they possibly come to blows?

China and Japans thriving commercial ties, one of the largest two-way trade relationships in the world, though, have failed to forge a closer political bond. In recent years, the relationship has taken on new and dangerous dimensions for both countries, and for the United States as well, an ally of Japans that it has signed a treaty to defend. Far from exorcising memories of the brutal war between them that began in the early 1930s and lasted more than a decade, Japan and China are caught in a downward spiral of distrust and ill will. There has been the occasional thawing of tension and the odd uptick in diplomacy in the seventy years since the end of the war. Men and women of goodwill in both countries have dedicated their careers to improving relations. Most of these efforts, however, have come to naught.

Asias version of the War of the Roses is being fought on multiple battlefields: on the high seas over disputed islands; in capitals around the world as each tries to convince partners and allies of the others infamy; and in the media, in the relentless, self-righteous, and scorching exchanges over the true account and legacy of the Pacific War. The clash between Japan and China on this issue echoes a conversation between two Allied prisoners of war in Richard Flanagans garlanded novel set on the Burma Railway in 1943, The Narrow Road to the Deep North. Memory is the true justice, sir, a soldier says to his superior officer, explaining why he wants to hold on to souvenirs of their time in a Japanese internment camp. Or the creator of new horrors, the officer replies.

In Europe, an acknowledgment of World War IIs calamities helped bring the Continents nations together in the aftermath of the conflict. In east Asia, by contrast, the war and its history have never been settled, politically, diplomatically, or emotionally. There has been little of the introspection and statesmanship that helped Europe to heal its wounds. Even the most basic of disagreements over history still percolate through day-to-day media coverage in Asia more than seventy years later, in baffling, insidious ways. Open a Japanese newspaper in 2017, and you might read of a heated debate about whether Japan invaded China, something that is only an issue because conservative Japanese still insist that their country was fighting a war of self-defense in the 1930s and 1940s. Peruse the state-controlled press in China, and you will see the Communist Party drawing legitimacy from its heroic defeat of Japan, though in truth, Chiang Kai-sheks Nationalists carried the burden of fighting the invaders, while the Communists mostly preserved their strength in hinterland hideouts. Scant recognition is given to the United States, who fought the Japanese for years before ending the conflict with two atomic bombs.

in which a trio of antagonists all simultaneously point guns at one another, creating a circle of dangerous, cascading threats.

In the east Asian version of this scenario, the United States has its arsenal trained on China. China, in turn, menaces Japan and the United States. In ways that are rarely noticed, Japan completes the triangle with its hold over the United States. If Tokyo were to lose faith in Washington and downgrade its alliance or trigger a conflict with Beijing, the effect would be the same: to upend the postwar system. In this trilateral game of chicken, only one of the parties needs to fire its weapons for all three to be thrown into war. Put another way, if China is the key to Asia, then Japan is the key to China, and the United States the key to Japan.

I left Tokyo for Hong Kong and China in 1995 after a five-year posting as a newspaper correspondent, soon after Japans then prime minister issued a heartfelt apology for the war. At the time, I remember feeling relieved that the issue seemed to have finally been put to rest. The history wars, though, far from ending, were just getting started. Over the ensuing two decades, under pressure from the Chinese Communist Party and abetted by Japanese revisionists, the same old issues have remained stuck on the front lines of regional politics.

Like east Asia more generally, the story of Japan and China is one of stunning economic success and dangerous political failure. China in particular has a whiff of the Balkans, where many young people have a way of vividly remembering wars they never actually experienced. A sense of revenge, of unfinished business, lingers in the system.

It may not require a war, of course, to deliver the last rites for Pax Americana. Washington could simply turn its back on the world under an isolationist president, a president, in other words, who simply did what Donald Trump promised to do on the campaign trail. America could also slip into unruly decline, with a weaker economy resulting in bits of empire, no longer financially sustainable, dropping off here and there.