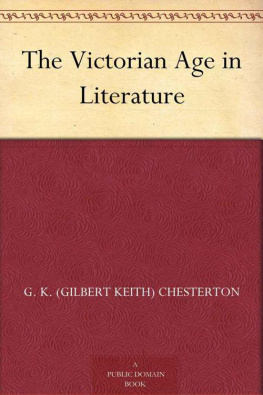

The Afterlife of Property

The Afterlife of

Property

DOMESTIC SECURITY

AND THE VICTORIAN NOVEL

JEFF NUNOKAWA

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

Copyright 1994 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

Nunokawa, Jeff, 1958

The afterlife of property : domestic security and the Victorian novel / Jeff Nunokawa.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-691-03320-X (alk. paper)

1. English fiction19th centuryHistory and criticism. 2. Domestic fiction, EnglishHistory and criticism. 3. Domestic relations in literature. 4. Homosexuality in literature. 5. Property in literature. 6. Marriage in literature. 7. Women in literature. 8. Sex in literature. I. Title. PR878.D65N86 1994 828.8dc20 93-30912 CIP

eISBN: 978-1-400-82463-2

R0

Acknowledgments

I HAVE LOOKED FORWARD for a long time to the moment when I would be able to thank the friends, teachers, colleagues, and acquaintances who have made this book possible. Many must be unaware of the help they suppliedsometimes no more than a perspicacious suggestion, sometimes no less than a way of life. They have provoked my best efforts and consoled me when I found it impossible to sustain them. Among these I thank first those who have read versions of the manuscript and offered advice and encouragement that made it possible for me to complete it: Amanda Anderson, Laura Brown, Bob Brown, Judith Butler, Cynthia Chase, Walter Cohen, Jonathan Culler, Ann Cvetkovich, Larry Danson, Maria DiBattista, Lynn Enterline, Billy Flesch, Judith Frank, John Guillory, Lanny Hammer, Rosemary Kegl, Tom Keenan, Uli Knoepflmacher, Deborah Nord, Adela Pinch, Jim Richardson, Lora Romero, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Mark Seltzer, Elaine Showalter, Margery Sokoloff, Jennifer Wicke, and an anonymous reader at Princeton University Press.

For help harder to name, I thank Alice Augenti, Phil Barish, Peter Brown, Leslie Brisman, Jill Campbell, Christina Crosby, Richard Elovich, Judy Foster, Diana Fuss, Richard Halpern, Beth Harrison, Phil Harper, Albert O. Hirschman, Walter Hughes, Molly Iuerelli, Haunani Lemn, Jack Levinson, Ann Lewis, Dave Lewis, Wellington Love, Loring McAlpin, Martin McElhiney, Wednesday T. Martin, Michael Meister, Carl Millholland, Wendy Millholland, David Miller, Dick Moran, John Murphy, Jill Nunokawa, Joyce Nunokawa, Scott Nunokawa, Walter Nunokawa, Lee Putnam, Laura Quinney, Gabriel Ramirez, Marcia Rosh, Adam Rolston, Andrew Ross, Joan Scott, Jim Siegel, Doreen Simpson, Sasha Torres, Tony Vidler, Sharon Willis, and Daniel Wolfe.

The Afterlife of Property

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

Think how terrible the fascination of money is!... I have money always in my thoughts and my desires; and the whole life I place before myself is money, money, money, and what money can make of life!

(Bella Wilfer, in Our Mutual Friend)

TRANSFORMATIONS OF CAPITAL

T HIS BOOK begins with the fears entertained in and beyond the Victorian novel about the powers of the commodity as they are embodied in four representative works written during the quarter-century Eric Hobsbawm calls the age of capital: For capitalisms discontents, the scandal of an economy characterized by the comprehensive grasp of the commodity form is the well-known story of its further spread, what Hobsbawm calls the major theme (xixii) of the third quarter of the nineteenth century, a theme whose modern and postmodern variations have resonated no less consequentially in the years since.

Such expansion has never been thought to confine itself to conquests at home or abroad of new outposts for trade or new sources of labor; more intimate infiltrations have always been noticed at work alongside capitalisms grander annexations; generations of its critics have traced its marks in the innermost recesses and resources of the cultures whose economy it comprehends; generations of capitalisms critics have witnessed it colonize all sorts of values defined by their difference from what can be bought and sold, transforming, Midas-like, everything it touches into tools or mirrors of its own image.

Ever renovated, this crisis of capital is nothing new: if the middle of the nineteenth century crowns the age that historians of capitalism identify as the period of its classic style and highest hopes,

However else we may have broken from the Victorian frame of mind, its outlines remain visible in our apprehension, traumatized or routine, that the commodity form, like a triumphal army or a thief in the night, has entranced regions of the psyche, precincts of culture and forms of labor whose worth had been measured by their distance from market value. Victorian prophets against the empire of the cash nexus have readied us to regard the deity Bulwer-Lytton declared the mightiest of all,

They reverberate as well through a tradition of cultural criticism inaugurated by Marxs meditations on the ideological aspects of capitalism, a tradition that has distinguished itself exposing the endless adumbrations of the commodity form beyond the commonly recognized borders of the marketplace, measuring its refractions through the prisms of reification all across the social horizon, discerning its comprehension, day and night, of the entire ensemble of social practices.

But our sense of the commoditys invasiveness may owe its largest debt neither to the eloquences of social prophecy, no matter how urgent, nor to the elaborations of social theory, no matter how perspicacious, but rather to the Victorian novel and its narrative heirs; for here, the diffuse, diffusive, subject of commodification comes home. The nineteenth-century novel never ceases remarking the reach of market forces into the parlors, bedrooms, and closets of a domestic realm that thus never ceases to fail in its mission to shelter its inhabitants from the clash of these armies. More often than not, this most influential of domestic monitors observes the saving distance between home and marketplace only in its breach. The novels celebration of domesticity as a sanctuary from the vicissitudes of the cash nexus is everywhere spoiled; everywhere the shades of the countinghouse fall upon the home.

How changed the house is, though! The front is patched over with bills, setting forth the particulars of the furniture in staring capitals. The bankruptcy auctions that erupt like occasional earthquakes upon the domestic landscape of the Victorian novel only begin to tell how the household goes the way of all capital even withinperhaps especially withinthe literary form most interested in promoting the home as the place where the man busy all day getting and spending might finally have some peace. These spectacular household failures serve notice of a ubiquitous insecurity; the buyers who swarm the halls and invade the upper apartments, pinching the bed-curtains, poking into the feathers, make examples of the domestic establishments they dissolve: these bleak houses remind all who see them that the forces of the market know where everybody lives.

The auctioneers housebreaking works to realize the pervasive condition of commodification that manages to hold all homes under constant threat: whenever household goods are put up for sale, we have reason to recall that they always can be. While such terroristic extensions of the markets long arm into the domestic realm are rare, they, like the arrival there of deathand the policeare frequent enough to remind everyone that they are always ready, always ready because the shape of the commodity, like the sentence of mortality and the watch of the law, comprehends all that dwells in the vanity fair described but hardly contained by the Victorian novel: Down comes the hammer like fate, and we move on to the next lot (201).