BETWEEN WOMEN

BETWEEN WOMEN

Friendship, Desire,

and Marriage in

Victorian England

Sharon Marcus

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2007 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Marcus, Sharon, 1966

Between women : friendship, desire, and marriage in Victorian England / Sharon Marcus.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-12820-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-691-12820-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-12835-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-691-12835-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. WomenEnglandHistory. 2. WomenSocial networksEngland. 3. LesbiansEnglandHistory. 4. Female friendshipEngland. 5. Women in Literature. I. Title.

HQ1599.E5M37 2007

306.848094209034dc22 2006020026

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon

Printed on acid-free paper.

pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

I NTRODUCTION

The Female Relations of Victorian England

P ART O NE

Elastic Ideals: Female Friendship

C HAPTER O NE

Friendship and the Play of the System

C HAPTER T WO

Just Reading: Female Friendship and the Marriage Plot

P ART T WO

Mobile Objects: Female Desire

C HAPTER T HREE

Dressing Up and Dressing Down the Feminine Plaything

C HAPTER F OUR

The Female Accessory in Great Expectations

P ART T HREE

Plastic Institutions: Female Marriage

C HAPTER F IVE

The Genealogy of Marriage

C HAPTER S IX

Contracting Female Marriage in Can You Forgive Her?

C ONCLUSION

Woolf, Wilde, and Girl Dates

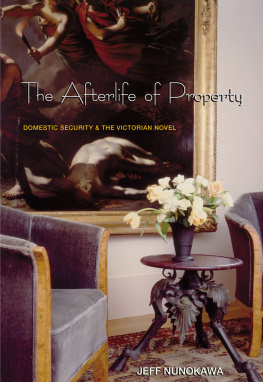

Illustrations

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Acknowledgments

F IRST AND FOREMOST I THANK the institutions who generously provided me with the time and support needed to research and write this book: the University of California, Berkeley; Columbia University; the American Council of Learned Societies, through the Frederick Burkhardt Residential Fellowship Program for Recently Tenured Scholars, and the School of Social Science at the Institute for Advanced Study.

I am deeply grateful to a series of brilliant research assistants whom I wont call tireless, since their sheer number suggests I wore them out all too quickly: Simon Stern, Karen Tongson, Susan Zieger, Matthew Lewsadder, Esther Pun, Jami Bartlett, Jill Salmon, Michele Hardesty, Kristi Brecht, Alexis Korman, Christine Leja, Avi Alpert, and Sydney Cochran.

It has been a pleasure to discover over and over again how others often understand what we are trying to say better than we do ourselves. This book would not exist without the help of colleagues who talked with me about my work and invited me to talk about it with others, especially Vanessa Schwartz, Richard Stein, Michael Wood, Deborah Nord, Claudia Johnson, Joan Scott, Judith Butler, Florence Dore, Elizabeth Weed, Ellen Rooney, Didier Eribon, Franoise Gaspard, Deborah Cohen, Masha Belenky, Margaret Cohen, Nancy Ruttenburg, Leah Price, Elaine Hadley, Andrew Miller, Ivan Kreilkamp, Deborah Cohen, Michael Lucey, Karen Tongson, Kate Flint, Martha Howell, Judith Walkowitz, Anne Higonnet, Carolyn Dinshaw, Anne Humpherys, Gerhard Joseph, Heather Fielding, Ruth Leys, Lila Abu-Lughod, Marianne Hirsch, Seth Koven, Jean Howard, and Susan Pedersen. Diana Fuss, Carolyn Dever, and Bonnie Anderson read the manuscript in its entirety and made superb suggestions for revision.

A particularly generous set of friends and colleagues offered help and comments at crucial junctures and on short notice: Ellis Avery, Dori Hale, Richard Halpern, Jeff Knapp, Hermione Lee, John Plotz, Christopher Nealon, Neil Goldberg, Cindy Hanson, Jennifer Callahan, Michael Lucey, Matt Pincus, and Alex Robertson Textor. Others have offered other forms of love and wisdom, especially Beth Biegler, Rena Fogel, Atsumi Hara, Ed Stein, Steve Lin, Anita Parately, and Sid Maskit.

Chapters 3 and 5 include significantly revised material from previously published essays. For permission to reprint material from Reflections on Victorian Fashion Plates, which appeared in differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 14.3 (2003), 427, I thank Duke University Press. For permission to use material from The Queerness of Victorian Marriage Reform, which appeared in Carol R. Berkin, Judith L. Pinch, and Carol Appel, eds., Exploring Womens Studies: Looking Forward, Looking Back (2006), 87106, I thank Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ. I also express appreciation to the University Seminars at Columbia University for their help in publication. Material in this book was presented to the University Seminar on British History.

It has been a delight to work with Hanne Winarsky, my incisive and enthusiastic editor at Princeton University Press, and with the expert staff there. A very special thanks as well to Kathy McMillan and Dimitri Karetnikov, who did a meticulous job of preparing the images, and to my wonderful copyeditor, Jennifer Liese.

The greatest pleasure of this project has been sharing it with Ellis Avery: tireless cheerleader, eagle-eyed editor, fabulous girlfriend, supportive partner, all-around sweetheart, and my merry accomplice in crimes against nature.

BETWEEN WOMEN

INTRODUCTION

The Female Relations of Victorian England

I N 1844 A TEN-YEAR-OLD GIRL named Emily Pepys, the daughter of the bishop of Worcester, made the following entry in the journal she had begun to keep that year: I had the oddest dream last night that I ever dreamt; even the remembrance of it is very extraordinary. There was a very nice pretty young lady, who I (a girl) was going to be married to! (the very idea!) I loved her and even now love her very much. It was quite a settled thing and we were going to be married very soon. All of a sudden I thought of Teddy [a boy she liked] and asked Mama several times if I might be let off and after a little time I woke. I remember it all perfectly. A very foggy morning. Emily Pepys found the mere idea of a girl marrying a lady extraordinary (the very idea!). We may find it even more surprising that she had the dream at all, then recorded it in a journal that was not private but meant to be read by family and friends. As we read her entry more closely, it may also seem puzzling that Emilys attitude toward her dream is more bemused than revolted, not least because her prospective bride is a very nice pretty young lady, and marrying her has the pleasant aura of security suggested by the almost Austenian phrase, It was quite a settled thing. Even Emilys desire to be let off so that she can return to Teddy must be ratified by a woman, Mama.

A proper Victorian girl dreaming about marrying a pretty lady challenges our vision of the Victorians, but this book argues that Emilys dream was in fact typical of a world that made relationships between women central to femininity, marriage, and family life. We are now all too familiar with the Victorian beliefs that women and men were essentially opposite sexes, and that marriage to a man was the chief end of a womans existence.