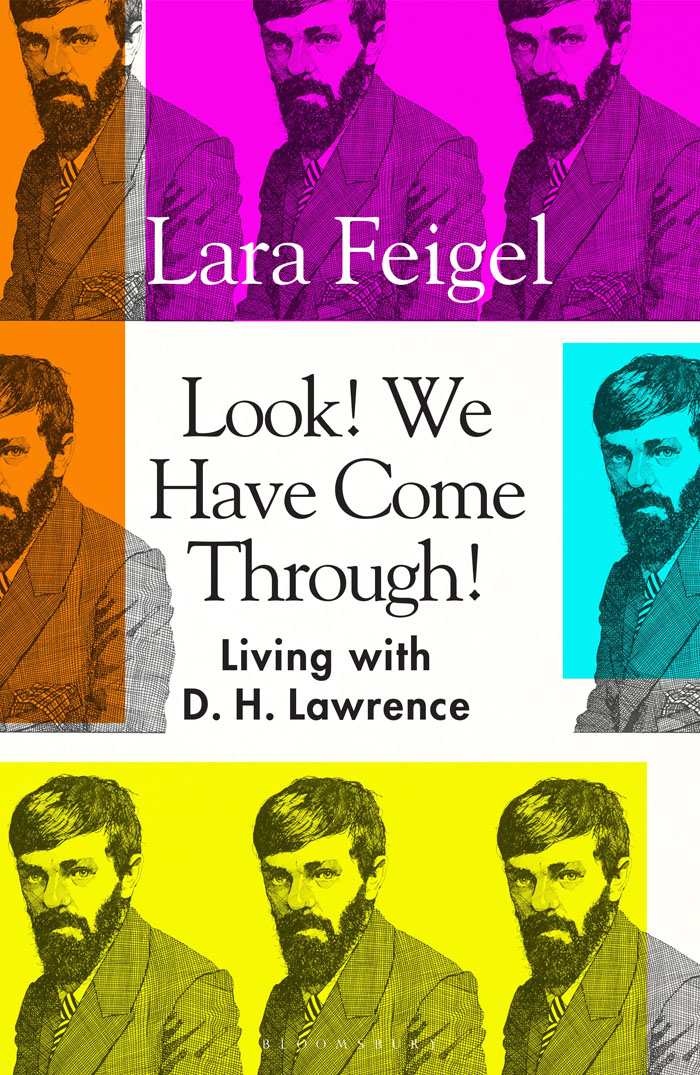

Lara Feigel - Look We Have Come Through: Living With D. H. Lawrence

Here you can read online Lara Feigel - Look We Have Come Through: Living With D. H. Lawrence full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Bloomsbury, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Look We Have Come Through: Living With D. H. Lawrence

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Look We Have Come Through: Living With D. H. Lawrence: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Look We Have Come Through: Living With D. H. Lawrence" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lara Feigel: author's other books

Who wrote Look We Have Come Through: Living With D. H. Lawrence? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Look We Have Come Through: Living With D. H. Lawrence — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Look We Have Come Through: Living With D. H. Lawrence" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Look! We Have Come Through!

For Patrick

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

Literature, Cinema, Politics, 19301945: Reading Between the Frames

The Love-Charm of Bombs: Restless Lives in the Second World War

The Bitter Taste of Victory

Free Woman: Life, Liberation and Doris Lessing

The Group

Contents

Ive got no idea about the names of the birds that wake us here in the mornings. I dont even know how to tell their calls apart. The little chirrups, the squawks, the glissandos that are easier to call song. But thankfully, I have D. H. Lawrence to guide me. It seems when we hear a skylark singing as if sound were running into the future, running so fast and utterly without consideration, straight on into futurity. Is that a skylark I hear? Or did the future they ran into so recklessly turn out to be a future in which they died out?

I am here, waking in a village in West Oxfordshire with two children and the ghost of D. H. Lawrence, because two weeks ago England went into lockdown and there was a scrambled game of musical chairs. We were to be enclosed within our households for several months. But what constituted a household? If we were to be thrown back into the nuclear families we had thought some combination of feminism and modernity had overcome, how were those not in families to arrange themselves? If you didnt already live with your partner, you were encouraged by the government either to move in with them or to say goodbye for months. So in the days that preceded lockdown, I hastily rented out our London flat and rented a cottage in Oxfordshire. We would be among the lucky few to have a garden; we would be near enough to my partner that we could just about describe ourselves as one household. I locked down with him, with my two-year-old daughter and eight-year-old son, and with D. H. Lawrence.

Lawrence is a necessity: I have agreed to write a book on him. This seems to me the moment for a new approach to Lawrence, now that were no longer mired either in the Lawrence worship led by F. R. Leavis in the 1950s or in the repulsion and condemnation led by Kate Millett in the 1970s. But Lawrence is necessary to me in another way, too. I am frightened by this loss of familiar community, this cutting off from conversation, this uncertainty about whether I am still part of the academic community I had an ambivalent relationship with in the first place. I have turned to Lawrence for urgent literary companionship, hoping that he will help me make sense of the new world we have found ourselves in. He promises to be well-suited to this. He was so adept himself at isolated living, so good a writer on extreme forms of proximity, so perpetually an outsider yet so foundational to his culture. And he is turning out to be an ideal guide as I navigate my new closeness to birds and flowers.

It was a decade ago, as I turned thirty, that I first formulated the idea of writing a book on him, and six years ago that I promised a book on Lawrence to my publisher. The catalyst for all this was a job interview. At a time when I was applying for every possible academic job, I accidentally got myself shortlisted for a lectureship in D. H. Lawrence studies at Lawrences nostalgically despised alma mater, the University of Nottingham, though I hadnt read a Lawrence novel for fifteen years. My last attempt at reading him had been when I got halfway through Sons and Lovers in impatient adolescence. No one had suggested I should read him as an undergraduate we were still living in Milletts shadow. So now I had three weeks to go straight from ignorance to expertise. I read Women in Love , and was irritated at first by all the wombs and loins, the flames and consummations I recalled from my last attempt. Then I came to the descriptions of sex. There is Ursula, kissed by Birkin, unsure at first because he seems so far away, and it was like strange moths, very soft and silent, settling on her from the darkness of her soul. And then we see them swooning together, deciding to wander off, somewhere we can be free somewhere where one neednt wear much clothes. Now when he kisses her, her arms closed round him again, her hands spread upon his shoulders, moving slowly there, moving slowly on his back, down his back slowly, with a strange recurrent, rhythmic motion, yet moving slowly down, pressing mysteriously over his loins, over his flanks. The sense of the awfulness of riches that could never be impaired flooded her mind like a swoon. They both write their letters of resignation and prepare to embark on an experiment in mutual freedom.

I swooned alongside her. It wasnt that I was seduced by Birkin I found his more pompous pronouncements as irritating as Ursula does. I was falling for the dialogue between Birkin and Ursula, the feeling that this was what a relationship could be, this delving into the unknown together with talk and touch. I turned out to love Lawrences prose, with its endless circlings moving slowly there, moving slowly on his back, down his back slowly the awkward off-kilteredness and uncertainty that is suddenly resolved, in the sumptuous clarification of that awfulness of riches. And I shared Ursulas restless energy, her feeling that life promised so much but delivered so little, that there must be forms of connection that went beyond the words love, sex that we use. I admired Lawrences writing of women. It seemed to me that few male novelists of his generation really thought about women, about their childhoods and adolescences and marriages, about their lives as daughters and as mothers, with the intensity and sensitivity that Lawrence did in this book, and in The Rainbow , which I read next, even if he sometimes got things wrong. Outrageous as it may seem, it felt to me that those repetitions and circlings were the rhythms of female thought. I liked the way that no one was ever still. No feeling was ever fixed, no view settled, before they were on to the next mood. I liked the way that relationships for him constitute constant gyrations of connection and alienation: it felt true to my lived experience.

This was the moment of conversion that so many readers among them so many women have had, both in Lawrences company (women frequently offered themselves to him, and his wife Frieda took them aside to tell them, not wholly inaccurately, that he was homosexual) and away from him. Visiting Lawrences shrine in Taos in 1939, W. H. Auden mocked the cars of women pilgrims

But I didnt write about him straight away. And in the years that followed years in which I had my first child and found myself drawn to writers of motherhood I moved away from him, relieved not to have ended up as a lecturer in D. H. Lawrence studies. Yet images and phrases from Lawrence kept coming back to me. I still admired Lawrences courage in writing openly about sex and bodily life (he was the first English writer to do so), and there were whole categories of experience that his writing continued to define. I decided to teach a Lawrence course and proposed a Lawrence book to my publisher. With my students, I read Simone de Beauvoirs and Kate Milletts coruscating critiques, and found it harder to feel that Lawrence spoke for me as a woman. Beauvoir loved his cosmic optimism; she fell for the scenes that I fell for, feeling that for Lawrence the sexual act is without annexation, without surrender of either partner, the marvellous fulfilment of each other, admiring his lovers because blending into each other, they blend into the trees, the light, and the rain. But then she decided that in fact Lawrence passionately believes in male supremacy, substituting the cult of the phallic for that of the Goddess Mother, granting all powers of thought and action to men. Twenty years later, after the 1960 trial of Lady Chatterleys Lover had chided and lauded Lawrence for championing the whole embodied life of men and women, the brilliantly enraged American feminist activist Kate Millett turned Beauvoirs ambivalence into something more angrily certain in her 1970 Sexual Politics , castigating Lawrence for propounding his personal cult, the mystery of the Phallus and in doing so bringing about a counter-revolution against women.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Look We Have Come Through: Living With D. H. Lawrence»

Look at similar books to Look We Have Come Through: Living With D. H. Lawrence. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Look We Have Come Through: Living With D. H. Lawrence and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.