Horatio Bottomley MP

This visitor seemed harmless enough, and it happened that the edition had gone to press, so a private secretary admitted him to the editors plush inner sanctum, all oak partitions and green leather. On one wall was a framed copy of the first John Bull front page, showing the English archetype in the company of a lugubrious bulldog; on another was an image of The Dicker, the editors country retreat. Rows of black deed boxes lettered in gold bore the names of legal adversaries, albeit that these were mainly for show, being mostly empty. On the mantelpiece was a life-sized cream bust of the late Charles Bradlaugh MP, the militant atheist, secularist, republican and free thinker Bottomley took pleasure in the widespread rumour, almost certainly false, that Bradlaugh was his father. On the desk was a photograph of the man himself, posing heroically with a sheaf of papers in hand, as though proclaiming the publications motto: If you read it in John Bull, it is so.

Behind the desk, fleshy and imperious, reposed Bottomley. He was a man capable of great magnanimity and utter unscrupulousness. Once a worker who had lost his legs in a lift accident hobbled all the way from Dulwich on two sticks to tell his story. Bottomley gave him two pounds, had his chaffeur drive him home, and pursued the story until it was satisfactorily resolved. On another occasion, he was visited by a well-known peer who having been made a minister of the crown suddenly craved popularity. Bottomley held his hand out: How popular would his lordship like to be? Better at making money than keeping it, Bottomley was prone to quixotic generosity. Told by his assistant that a favourite railway attendant of his was in prison, he responded: Why, we must send money to his wife at once. Advised that the man was in prison for bigamy, he adjusted: Well, we must send money to both his wives.

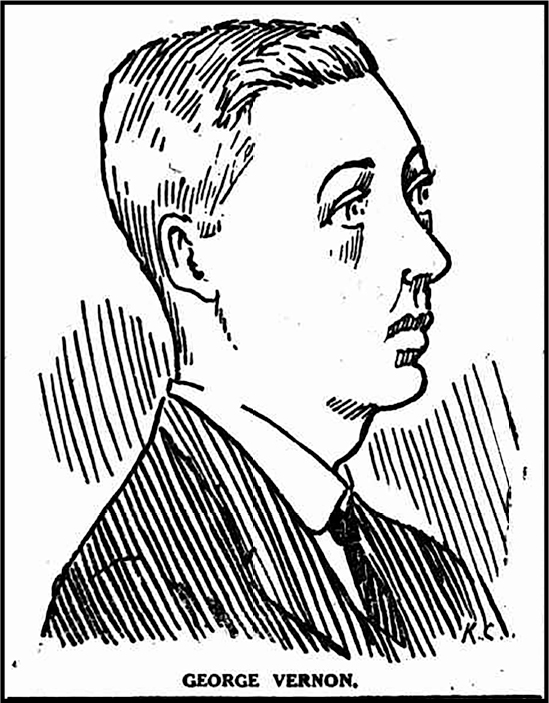

Bottomley now sought to appraise his visitor, who introduced himself as George Vernon. He was short, stocky, brown-haired, clean-shaven, well-attired, in his mid-twenties. His accent located him among the well-to-do. So Bottomley was surprised when George Vernon divulged the reason for his visit. The reason was murder.

Surprised, and also delighted. Bottomley liked murder. Before John Bull, he had owned Londons Sun, turning it from a rather staid and sober news sheet into something more popular and, for the times, vulgar. Its approach to violent crime was often original. Bottomley opened an appeal for the daughter of Bennett the Yarmouth murderer, whom he had made a ward in chancery after her fathers execution; he fought to save Gardner the alleged Peasenhall murderer from a triple jeopardy trial, after two hung juries. On the day in July 1903 when Samuel Dougal, the Moat Farm murderer, was hanged at Chelmsford Prison, the Sun printed a facsimile of his confession nobody knew if it was genuine but, of course, its authorship could no longer be challenged.

Most notoriously, in September 1910, John Bull had pulled off the coup of publishing a confession by the infamous poisoner Dr Crippen, although its provenance had quickly become controversial. Bottomley had been surreptitiously subsidising Crippens defence on the understanding that John Bull would receive the accuseds final testament exclusively. Brother, how came you to do it? Bottomley asked Crippen by letter. What demon possessed you? Relieve your burning brain, confiding to me the name of your accomplice. But when the plan had been thwarted by the prison governor, Bottomley had dictated a confession himself.

Crippens solicitor Arthur Newton had just been suspended from the rolls for attesting the confessions veracity; Bottomley, unpunished and unchastened, now seemed to be in proximity to another such story. Was it true? Was it false? Did this matter? When the young man explained that he wished to make a statement, Bottomley excitedly took up his pen. His first job had been as a court stenographer; he had excellent shorthand. Giving his name as George Valentine Jeffray Vernon, the visitor commenced: I am the son of the well-known Middlesex cricketer. I was at the time I speak of under twenty-five years of age. My life had been a stormy one

1 A HARD MAN

O n the face of it, George Vernons life should not have been stormy at all. On the contrary, he had been born with what appeared a host of advantages, including the patrimony to which he drew Bottomleys attention. George grew up idolising his father and adoring his mother and not without good reason.