Scribe Publications

ASBESTOS HOUSE

Gideon Haigh has been a journalist for more than twenty years. His books range from One of a Kind: the story of Bankers Trust Australia 19691999 , Bad Company: the cult of the CEO , to The Vincibles: a suburban cricket season . He lives in Melbourne.

for Philippa

Scribe Publications Pty Ltd

1820 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

2 John Street, London, WC1N 2ES, United Kingdom

First published by Scribe 2006

Copyright Gideon Haigh 2006, 2007

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher of this book.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data

Haigh, Gideon.

Asbestos house.

9781925113457 (e-book)

1. James Hardie Industries - History. 2. Asbestos industry - Health aspects - Australia. 3. Building materials industry - Australia - History. 4. Asbestos - Toxicology - Australia. 5. Asbestos abatement - Australia. I. Title.

338.7691950994

scribepublications.co.uk

scribepublications.com.au

Contents

Prologue:

Epilogue:

Prologue

I really thought he would want to know

ON THE AFTERNOON OF 15 MAY 2001 , three men met briefly in a small office in a Sydney commercial building. The trio knew one another well. Their greetings were cordial and the tone of their conversation friendly the only hint of an underlying tension was a single gesture, which would haunt all of them. Peter Macdonald, the chief executive of James Hardie Industries, would be hounded from office. Sir Llew Edwards, a former Hardie director, and Dennis Cooper, a past Hardie executive, would be plunged into four enervating years of public controversy. Diseases borne quietly by numberless thousands of suffering people would be revealed as the public health crisis they constitute.

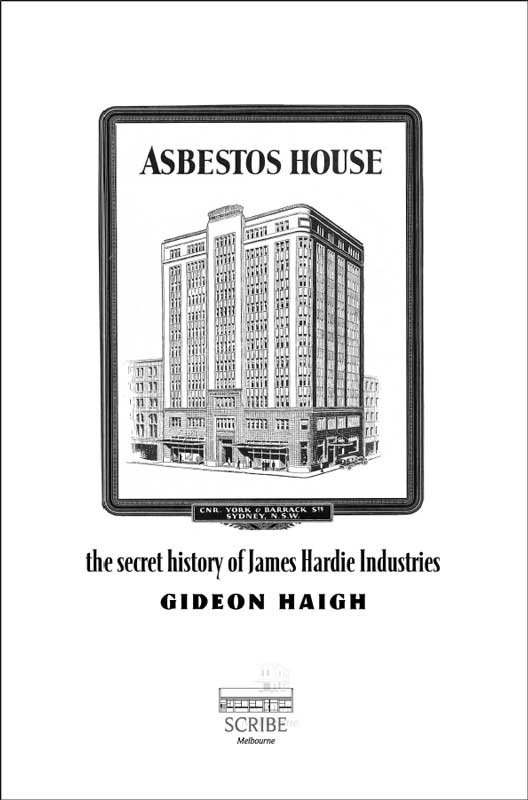

No tables were thumped and no voices raised that day, and none in the affair really were until very near its end, even if few business stories in Australian history have ramified quite so widely and deeply. The devil, instead, was in the detail. The location itself was richly resonant. Seventy-five years had elapsed since Macdonalds employer had acquired the site at the corner of York and Barrack Streets, paying 95,000 for land occupied by a derelict warehouse. The tower that the company erected symbolised its aspirations rather than reflecting its stature. Moving staff in took just a day, personnel simply carrying their desks and documents across the street from temporary quarters in the Alcocks Building diagonally opposite. The buildings christening, however, involved a confident statement about its owners future: what became James Hardie Asbestos took up residence at Asbestos House.

Fifty years to the month had passed since Hardie had given a mortgage over the building to the AMP to see it through a period of financial turbulence one that led on to one of the great post-war business success stories, as Hardies asbestos cement, known popularly as fibro, spread across the Australian landscape. And with none of the eerie ring its name would later take, Asbestos House seemed an expression of its builders blue-chip solidity. It featured prominently in the companys advertising; stockists knew its telephone number, B7721, by heart; by the mid-1950s, Hardie occupied all twelve floors, with the ground level remodelled as a showroom by Gordon Andrews, later the designer of Australias decimal currency. Visitors flocked to events like its Sydney of Tomorrow exhibition, whose centrepiece was a giant scale model of the Sydney Opera House in its original design. As recently as the mid-1970s, Asbestos House was the workplace of as many as 300 employees.

Twenty-five years on, the building had a different symbolic significance. It was showing its age. After decentralisation and downsizing, Hardie occupied only two-and-a-half floors, and none too happily. Despite renovations in the mid-1980s, employees now found the place heavy, dark and airless, its small windows impossible to open. It was like a prison, recalls one Hardie executive, who found he needed glasses after about a year working there. The building was no longer even Hardies, having been sold and leased back in the late 1980s; the lease was coming up, in fact, and Hardie wasnt planning to renew.

Most particularly, it was no longer called Asbestos House. With the materials latter-day connotations of death and disease, the building had, like the company, shed its old moniker in 1979. James Hardie House remained the house that asbestos built, and James Hardie Industries the company that asbestos had made, but the meeting that day concerned a sealing off of that past now almost complete. Macdonald himself no longer even maintained an office in the building, his usual workspace being an unostentatious corner of Hardies Californian headquarters at Mission Viejo, between Los Angeles and San Diego. When he came to Sydney for group management team meetings, as he had on this occasion, he simply flipped open his laptop in one of the companys lookalike nooks on the eighth floor. Such was his nature. Macdonald scorned the normal trappings of seniority. He had no personal assistant, shared a secretary and did his own typing. He flew economy class everywhere, booking flights for himself. His reserves of smalltalk were negligible, his personal austerity a byword among his executive circle. Even his smile seemed economical: a reflex rictus rather than a hint of unguarded warmth.

For all this, Sir Llew Edwards was an admirer, even thinking of Macdonald as a friend. The former deputy premier of Queensland set great store by ceremony, and found Macdonald unfailingly gentlemanly and courteous. And Cooper, while he found Macdonald personally remote, admired his acute and unflagging attention to detail. It was this, in fact, that had made the events bringing their meeting about so surprising. Three months earlier, Edwards as chairman and Cooper as managing director had joined the board of a trust called the Medical Research and Compensation Foundation composed chiefly of two entities that had formerly been subsidiaries of James Hardie Industries: Amaca Pty Ltd, previously James Hardie & Coy Pty Ltd, and Amaba Pty Ltd, previously Jsekarb Pty Ltd. In days gone by, both had manufactured products containing asbestos; in the last twenty years or so, accordingly, they had been named as defendants in a host of compensation claims by sufferers of asbestos-related diseases. Their consignment to the foundation with net assets of $293 million had been sold to the stockmarket as Hardies last parting from its fibrous past. The foundation, essentially Cooper and his secretary, had set up shop, as an interim arrangement, in suite number 602 on the sixth floor of Hardie House. Claims themselves were processed by essentially the same team that had done the job at Hardie, which had turned itself into a consultancy a block away in York Street called Litigation Management Group under the direction of its old boss Wayne Attrill.

On Wednesday 11 April, however, Cooper had received from LMG a financial accounting of the foundations operations which puzzled him. The report revealed net litigation costs before insurance recoveries of $32 million for the year ended 31 March, and projected similar costs for the year just underway. This stood at odds with the cost expectations of the actuaries Trowbridge, on whose figurings the foundation had been established, of nearer $22 million: the result was a budget based on the LMG numbers featuring an unsightly black hole, and a future alarmingly curtailed. Still more disturbing was the explanation at which Cooper arrived for the discrepant numbers. Trowbridges calculations seemed to have excluded nine months of claims data to the end of calendar 2000. Coopers apprehensions were not eased when he rang Attrill, who had been part of the Hardie team that had devised the MRCF. I thought you knew, Attrill insisted. I thought you knew the latest data wasnt used. Cooper was perplexed: No, I did not. Id have thought that an up-to-date actuarial forecast would have used the most recent information.

Next page