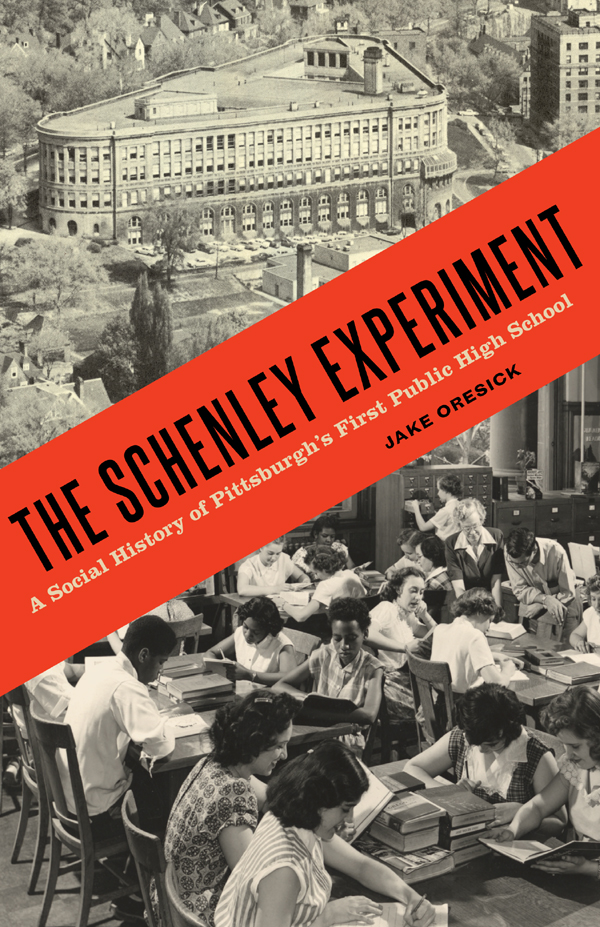

The Schenley Experiment

The Schenley Experiment

A Social History of Pittsburghs First Public High School

Jake Oresick

The Pennsylvania State University Press

University Park, Pennsylvania

Keystone Books are intended to serve the citizens of Pennsylvania. They are accessible, well-researched explorations into the history, culture, society, and environment of the Keystone State as part of the Middle Atlantic region.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Oresick, Jake, 1982, author.

Title: The Schenley experiment : a social history of Pittsburghs first public high school / Jake Oresick.

Description: University Park, Pennsylvania : The Pennsylvania State University Press, [2017] | Keystone Books. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Traces the history of Schenley High, Pittsburghs first public high school. Includes 150 original interviews examining issues of class, race, ethnicity, and collaboration, and how these reflect on the history of education in PittsburghProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016053627 | ISBN 9780271078335 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Schenley High School (Pittsburgh, Pa.)History.

Classification: LCC LD7501.P6 O74 2017 | DDC 373.74886dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016053627

Copyright 2017

The Pennsylvania State University

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by

The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 16802-1003

The Pennsylvania State University Press

is a member of the

Association of American University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to

use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy

the minimum requirements of American National Standard

for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for

Printed Library Material, ansi z39.481992.

Additional credits: pages iiiii, photo by Mark Knobil;

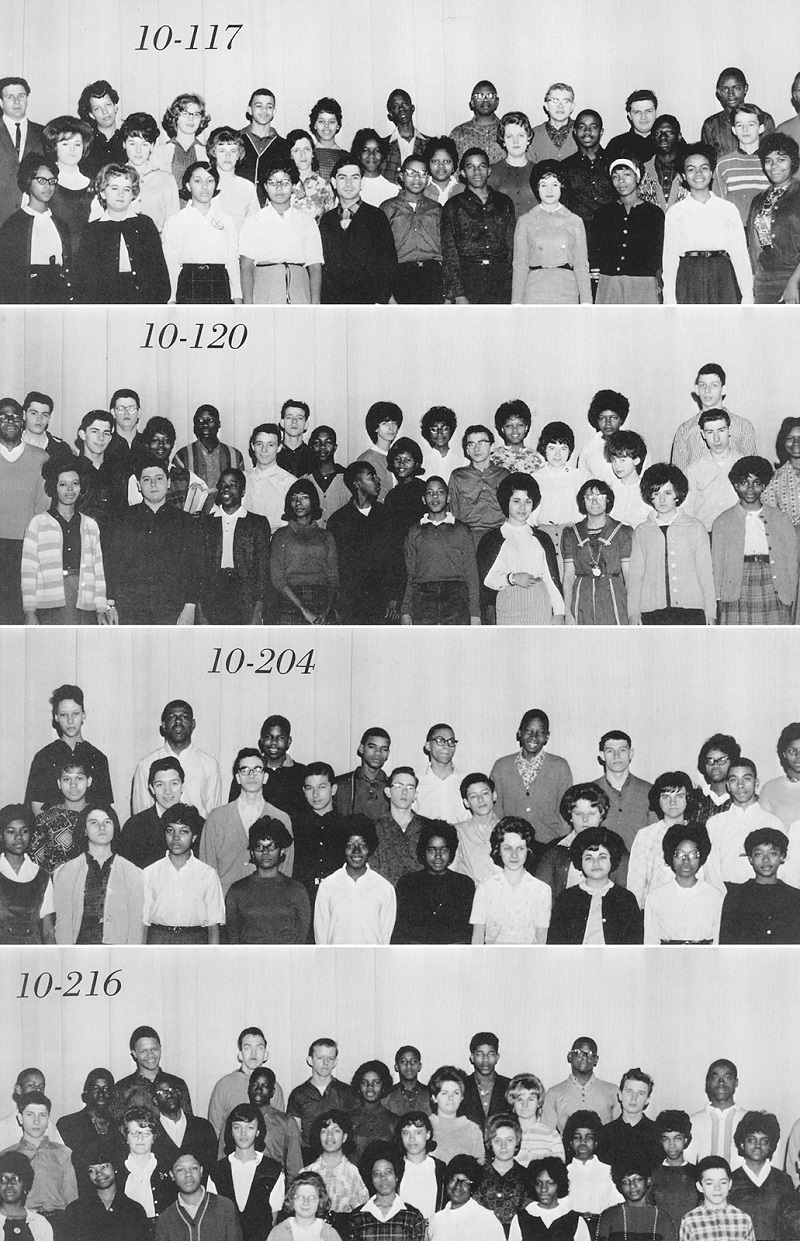

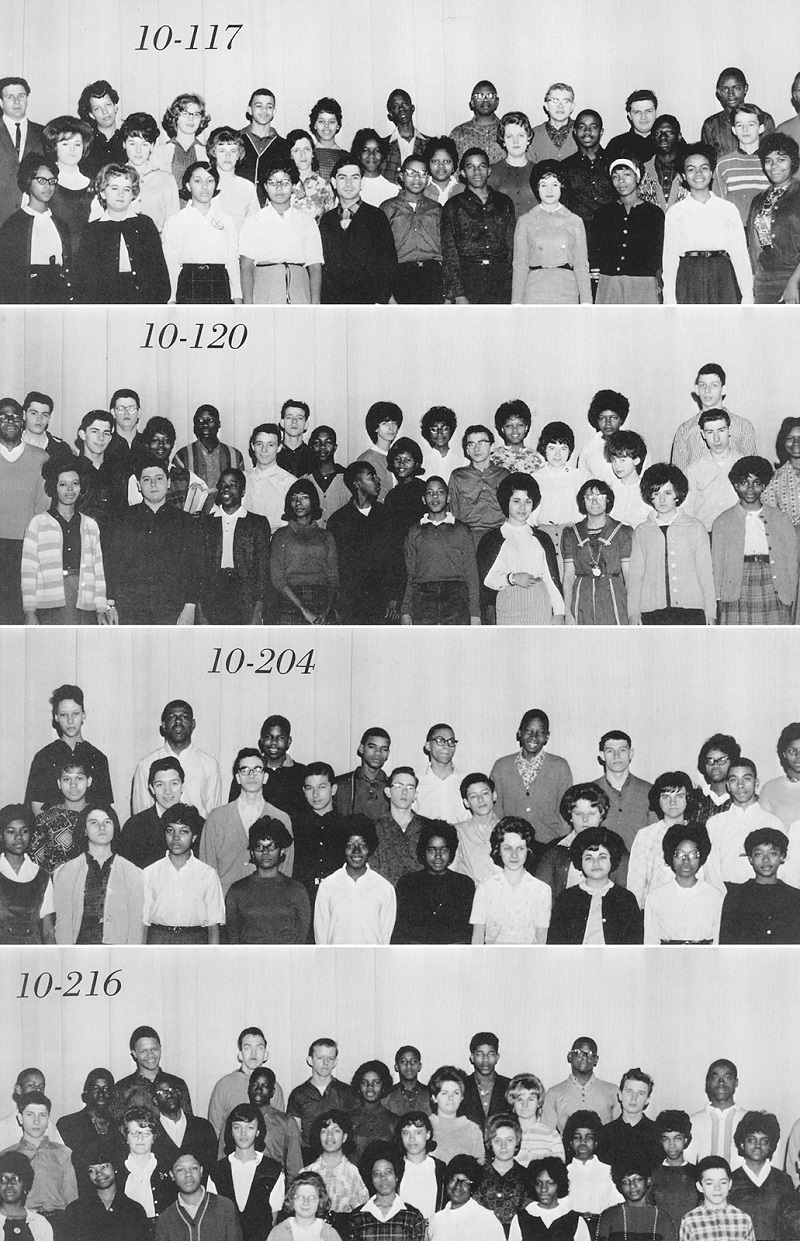

page vi, photo from The Journal (Schenley High School), 1963.

For my parents, Stephanie and Peter, and all they stood in line for.

CONTENTS

The author is indebted to many, especially the more than 350 present and former Pittsburgh Public Schools stakeholders who contributed their stories to this book. Particular thanks is owed to the following individuals, without whose knowledge, counsel, and resourcefulness this book would be far inferior: Susan (Forgrave) Monroe and every educator who participated; James Hill 11; Jim Burwell 65, and the classes of 1964 and 1965; Annette Werner; Mary Ellen Kirby, and the classes of 1987, 1988, and 1989; Ralph Proctor 56; Leon Boykins 03; and Tina Calabro.

Thanks to the Pennsylvania State University Press, for giving us, the Schenley High School community, a clearer and more powerful voice, and a forum to memorialize our collective story. To the Presss capable staff, and to Kathryn Yahner in particular, the author is ever appreciative of your faith in this project, and your editorial wisdom and patience. Recognition is also due to the Jack Buncher Foundationwhose generous grant helped commission or license many illustrations hereinand to the following institutions that provided research support: the Carnegie Library of Pittsburghs Pennsylvania Department and William R. Oliver Special Collections Room; the Senator John Heinz History Centers Detre Library & Archives; and the Pittsburgh Public Schoolss administrative staff and Law Department.

Grateful thanks to the family and friends who supported this project and its author over the last four years. Special appreciation is owed to the following, for their enduring enthusiasm and indulgence: Edith Flom Schneider; Stephanie Flom; Peter, William, David 03, Mandi, Deanna, Anna, Adelyn, and Will Oresick; Nate Gerwig 01; Shawn Robinson; Lauren Byrne Connelly; Grant Berry; Nick Bisceglia; Brad Calhoun; Courtney Zarra; Lauren Bachorski; Christopher Kempf; Molly Delaney; Josh and Amanda Hausman; Elizabeth Ross Radigonda; Carole Beck; and Debbie ODell-Seneca. Finally, thanks to Alina La Keebler, whose book, The History and Architecture of the Henry Clay Frick School (Pittsburgh: Frick ISA, 1996), inspired this one, and to Janine Jelks-Seale 00, whose accidental poetry became this books working title, and ultimately the title of chapter 2.

On a September morning in 1855, Pittsburghs first public high school opened in a cramped, rat-infested storefront on Smithfield Street. Over the next 156 years, the unusually diverse school served as a social incubator in a largely segregated city, illuminating the raw effects of the Progressive Era, urban renewal, Martin Luther King riots, and court desegregation battles. Pittsburgh Central High School (known as Central)recast as Schenley High School in 1916was at different times the subject of innovative investment and destructive neglect, providing a case study in both the best and worst urban public education practices. The Schenley Experiment tells the story of Pittsburgh and its public school districtof class, race, ethnicity, and collaborationthrough the prism of its oldest and most dynamic high school.

The school often reflected the regional zeitgeist; its mere creation angered taxpayers, who viewed a high school in an industrial city as a public waste. However, the school also defied stereotypes of Pittsburgh as provincial and prejudiced. Central High was utterly cosmopolitan, offering rigorous, college-caliber instruction and serving as a pipeline to the Ivy League. Admission was exclusive but meritocratic, and black students enrolled at least nine years before the state banned school segregation.

When the Central school building became antiquated, the new Schenley building was designed as a forward-thinking In 1930, the majority of students came from distant city neighborhoods and suburbsareas zoned for other high schools.

Most remarkably, Schenley often outpaced the nations social progress. The school embraced diversity, bragging about its cosmopolitan throngLittle Rock Nine braved a mob, Schenleys senior class board featured black, white, and Chinese American students.

The school was no utopia, however, with instances of discrimination, latent class tensions, and no black teachers for nearly a century. Even into the 1970s, some counselors tried to talk college-track blacks into attending trade school. In the twenty years after Brown v. Board of Education, the loss of middle-income housing in Oakland, as well as civil rights unrest in the adjacent Hill District, dramatically reduced white enrollment, from 56 percent to 18 percent. Many middle-class blacks also abandoned Schenley. Soon the District diverted resources away from the shrinking school. Accordingly, the 1970s were marked by an antiacademic culture, with graffiti on walls and marijuana smoke in stairwells. Black leaders demanded that Schenley and other schools be integrated, observing that only schools with white students were adequately resourced. The District implemented forced busing and manipulated many schools residency boundaries to overcome geographic segregation. Some whites obstructed with legal challenges, boycotts, and violence. Although busing brought balance to many schools, Schenley was not among them. In 1981, the state Human Relations Commission moved to disband the nearly all-black school, then the citys lowest achieving, for noncompliance with a thirteen-year-old desegregation order.