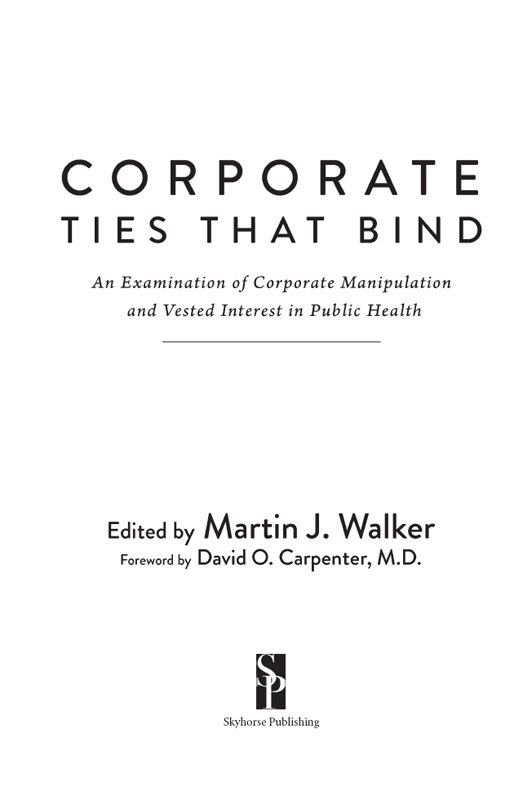

Copyright 2017 by Martin J. Walker

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-1188-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-1189-1

Printed in the United States of America

DEDICATION

DR. IRVING J. SELIKOFF

Dr. Irving J. Selikoff (19151992), a New York physician based at Mount Sinai Hospital, was the leading American medical expert on asbestos-related diseases between the 1960s and early 1990s. Selikoff was consistently demonized as a media zealot who exaggerated the risks of asbestos on the back of bogus medical qualifications and flawed science. Since his death, the criticism has become even more vituperative and claims have persisted that he was malicious or a medical fraud. However, most of the attacks on Selikoff were inspired by the asbestos industry or its sympathizers, and for much of his career he was the victim of a sustained and orchestrated campaign to discredit him.

From Shooting the Messenger: the Vilification of Irving J. Selikoff,

J. McCulloch and G. Tweedale

DR. ALICE STEWART

Alice Stewart, (19062002) achieved worldwide fame, and changed medical practice, through her tenacious investigations and demonstration of the connection between foetal x-rays and child cancers. She went on to attract the enmity of the nuclear and health physics establishmentsand the hostility of the British and American governmentsby insisting that her studies showed that the adverse effects of exposure to low-level radiation were far more serious than had been officially accepted. Stewarts entire life and career were devoted to social medicine, to the improvement of the lives of others, and to the bitter battles that have to be fought to ensure that findings contrary to policy or received wisdom are investigated in a balanced and adequate way and, where necessary, acted upon.

From the Obituary of Alice Stewart by Anthony Tucker

CONTENTS

David O. Carpenter

Martin J. Walker

David Egilman, Susanna Rankin Bohme, Lelia M. Menndez, and John Zorabedian

Lennart Hardell

Richard Clapp

Bo Walhjalt

Neil Pearce

Kathleen Ruff

Geoffrey Tweedale

Martin J. Walker

Christian Blom

Gunni Nordstrm

Gayle Greene

Martin J. Walker

Bo Walhjalt and Martin J. Walker

Rory ONeill, Simon Pickvance, Andrew Watterson

Don Maisch

Janine Allis-Smith

Devra Davis

Pierre Mallia

Jody Warren

Jock McCulloch

Andrew Watterson

Nicola Wright

Janette Sherman

PREFACE

David O. Carpenter

O ne of the greatest problems in scientific discovery is the perversion that can result due to conflicts of interest. While there are other possible bases for conflicts of interest, most are financial. Individual scientists may have financial conflicts of interest that influence the design of the studies they perform so that they obtain a result similar to that which they, or their funders, want. When funding for scientists comes from an organization or corporation with desires to present a clean bill of health to the public, there is strong motivation to give the funder what they want, if only to continue receipt of funding.

The most egregious epidemiological Judas in modern times is probably Sir Richard Doll, who for years took significant amounts of money from Monsanto, Dow Chemical, and the Chemical Manufacturers Association in return for making strong public statements denying that chemicals and radiation cause cancer. Because of his distinguished position, his viewsthough they fail to take into account the impact of hundreds of carcinogenic chemicals in our food, water, and air, and how these exposures increase rates of cancer in the general populationstill have significant influence on public policy.

Corporations themselves have both more power and more money than most individual scientists to influence how scientific and epidemiological results are perceived by the scientific and general public, and especially by the regulatory and political bodies that determine whether restrictions are placed on products and their use. The financial return from development and sale of chemicals and some high-tech products can be enormous, and the temptation to ignore, hide, or deny problems by any means possible is great. This book offers an introduction as to how corporations can, and have, distorted knowledge and actions on health impacts of products in which they had financial interests.

There are a variety of ways that industry can pervert or manipulate knowledge of the toxicity of products in which they have financial interest. Many corporations have their own research units and actively participate in scientific meetings and the publishing of research results. But the outcomes of this research are often, indeed usually, controlled by the corporate management such that adverse effects of their product are not released, even if found by their own research.

Often adverse effects from internal testing are hidden under the ruse that the results are proprietary. There are numerous examples of disease outcomes where industry-funded research failed to detect hazards but government-funded research showed significant adverse health effects. If research is carried out by teams beyond the corporation, they can still to some extent control the outcome by controlling the provision of raw data.

In the laboratory, it is always possible to obtain negative results if that is the desire. One can manipulate the assay sensitivity so as not to detect an effect. One can study a limited number of animals or people so that any results obtained are not statistically significant. One can fail to follow the animals or the people for a sufficient period of time so as to detect health effects, especially if the effect is something with a long latency, such as cancer. Or one can look for only acute effects, such as LD50, when the real concern is either a subtle change in cognitive function and behavior or a long-term alteration in reproductive function.

There are several common tactics used by industry to pervert or manipulate the results of scientific research and the way in which products are perceived after they come onto the market. Often independent researchers whose studies demonstrate adverse effects of an industrial product in which the corporation has a financial interest are described publicly as being advocates, fringe, or even poor scientists. This tactic is facilitated by the fact that any responsible scientist will always indicate both the strengths and weaknesses associated with their results in their publications.

Industry often inappropriately takes such weaknesses to publicly discredit the investigator while minimizing the importance of the results. When this is not enough, corporations can resort to harassment of independent scientists and others. This may take the form of accusations of misconduct or impropriety, or (at least in the United States) by demanding access to all unpublished data and documents through a Freedom of Information Law (FOIL). On occasion it means direct legal action against scientists, authors, journalists, or campaigners alleging defamation or loss of income as a result of statements concerning the dangers from the industrial product.