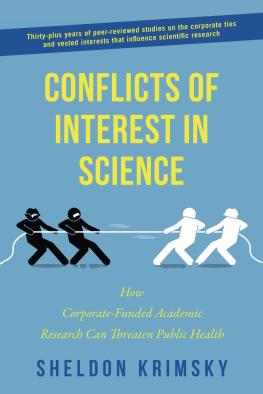

Copyright 2019 by Sheldon Krimsky

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Hot Books, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Hot Books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Hot Books and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

Cover design by Jennifer Houle

Cover photo credit: iStock

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-3652-8

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-3653-5

Printed in the United States of America

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My collaborators over thirty years have been an inspiration and provided special knowledge that made our research possible. I want to give special thanks to: the late James Ennis, sociologist at Tufts; Les Rothenberg, bioethicist, formerly at University of California at Los Angeles; to my collaborator Lisa Cosgrove, psychologist U. Mass Boston, who conceptualized the studies of conflicts of interest in the DSM and clinical guidelines for psychopharmacological drugs; Harold J. Bursztajn, psychiatrist, Harvard Medical School; and Tim Schwab, journalist, formerly with Food & Water Watch. My appreciation also goes to Anna Sangree, who helped edit and format the manuscript in its early stages.

CONTENTS

19851995

The Corporate Capture of Academic Science and Its Social Costs, Genetics and the Law III. Proceedings of the Third National Symposium on Genetics and the Law , April 24, 1984. Aubrey Milunsky and George Annas (eds.) (New York: Plenum Press, 1985, 4555).

Academic-Corporate Ties in Biotechnology: A Quantitative Study, Science, Technology and Human Values 16, no. 3 (Summer 1991): 275287.

Science, Society, and the Expanding Boundaries of Moral Discourse, Science, Politics and Social Practice, Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science (Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1995).

19962006

Financial Interest of Authors in Scientific Journals: A Pilot Study of 14 Publications, Science and Engineering Ethics 2, no. 4 (1996): 395410.

Financial Interest and Its Disclosure in Scientific Publications, JAMA 280, no. 3 (July 15, 1998): 225226.

The Profit of Scientific Discovery and Its Normative Implications, Chicago Kent Law Review 75, no. 1 (1999): 1539.

Conflict of Interest and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis, JAMA 282 (Oct. 20, 1999): 14746.

Conflict of Interest Policies in Science and Medical Journals: Editorial Practices and Author Disclosures, Science and Engineering Ethics 7 (April 2001): 205218.

Autonomy, Disinterest, and Entrepreneurial Science, Society 43, no. 4 (May 2006): 2229.

Financial Ties between DSM-IV Panel Members and the Pharmaceutical Industry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 75 (2006): 154160.

The Ethical and Legal Foundations of Scientific Conflict of Interest, in Law and Ethics in Biomedical Research: Regulation, Conflict of Interest, and Liability Trudo Lemmens and Duff R. Waring, eds. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006).

20072017

When Sponsored Research Fails the Admissions Test: A Normative Framework, in: Universities at Risk: How Politics, Special Interests, and Corporitization Threaten Academic Integrity , James L. Turk, ed. (Toronto, James Lorimer & Co., 2008).

Conflicts of Interest and Disclosure in the American Psychiatric Associations Clinical Practice Guidelines, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 78 (2009): 228232.

Science in the Sunshine: Transparency of Financial Conflicts of Interest, Ethics in Biology, Engineering and Medicine 1, no. 4 (2010): 273284.

Combating the Funding Effect in Science: Whats Beyond Transparency? Stanford Law and Policy Review 21 (2010): 101123.

Beware of Gifts That Come at Too Great a Cost: Danger Lurks for State Universities When Philanthropy Encroaches on Academic Independence, Nature 474 (June 9, 2011): 129.

Do Financial Conflicts of Interest Bias Research? An Inquiry into the Funding Effect Hypothesis, Science, Technology and Human Values 38, no. 4 (2012): 566587.

A Comparison of DSM-IV and DSM-5 Panel Members Financial Associations with Industry: A Pernicious Problem Persists, PLOS Medicine 9, no. 3 (March 2012): 14.

Tripartite Conflicts of Interest and High Stakes Patent Extensions in the DSM-5, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 83 (2014): 106113.

Conflicts of Interest among Committee Members in the National Academies Genetically Engineered Crop Study, PLOS ONE 12, no. 2 (Feb. 2017): e0172317.

Conflict of Interest Policies and Industry Relationships of Guideline Development Group Members: A Cross-Sectional Study of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Depression, Accountability in Research 24, no. 2 (2017): 99115.

FOREWORD

BY A RTHUR C APLAN

We should not need to be reminded about the importance of scientific evidence in forming public policy in modern society. But in this day and age of fake news and science denialism we need to be. Sheldon Krimsky notes in his introduction to this volume, which collects his most important studies on the topic of conflicts of interest and science, that a scientific establishment dedicated to the pursuit of credible, verifiable knowledge unbiased by political, economic, or personal interests is essential. Oltherwise, a society cannot guarantee that its citizens will have access to reliable information that will enable them to make informed political, social, and medical decisions. Many may take this reminder for granted. They shouldnt.

Science and medicine are under attack as never before in the years since World War I. The world witnessed the emergence of modern science as a key element fueling atrocities in wealthy societies, ranging from Nazi Germanys reliance on race hygiene rooted in genetics and social Darwinism to eventually justify the murder of the disabled and then the Holocaust, and the use of fraudulent biology in Soviet agriculture and the mass starvation that resulted attributable, in part, to Lysenkoism. Science in the service of ideology rather than truth cost the lives of hundreds of millions.

Americas emergence as a world power during WWII fueled by science and technology and Britains ability to fend off defeat by Germany through the application of science in manufacturing, air defense, avionics, naval warfare, and civilian defense showed the value of sound evidence put in the service of democracy. Later in the twentieth century American quality of life would continue to improve due to advances in medicine, agriculture, engineering, chemistry and other sciences fueled by publicly funded research in universities, academic medical centers, government agencies and labs, and corporate labs.

By the time of the Cold War, Korea and the Vietnam War Americans looked to science to make them victorious over their ideological foes. Americas first real engagement with the issue of conflicts of interest arose around government military spending on nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons; efficient delivery systems for these weapons; satellite and other forms of surveillance; and psychological warfare techniques. Some scientists protested the glut of government funding for the military that surged through the universities and labs. Some citizens did as well. But, science in the service of war became highly profitable for universities and their tech industry spinoffs. The agenda of many areas of science were set not by pure inquiry but by their utility for military application. Science in America, once the province of highbrow intellectuals and engineers seeking to solve challenges of daily life became big business with big consequences for what got studied, peer-reviewed, published, and rewarded.