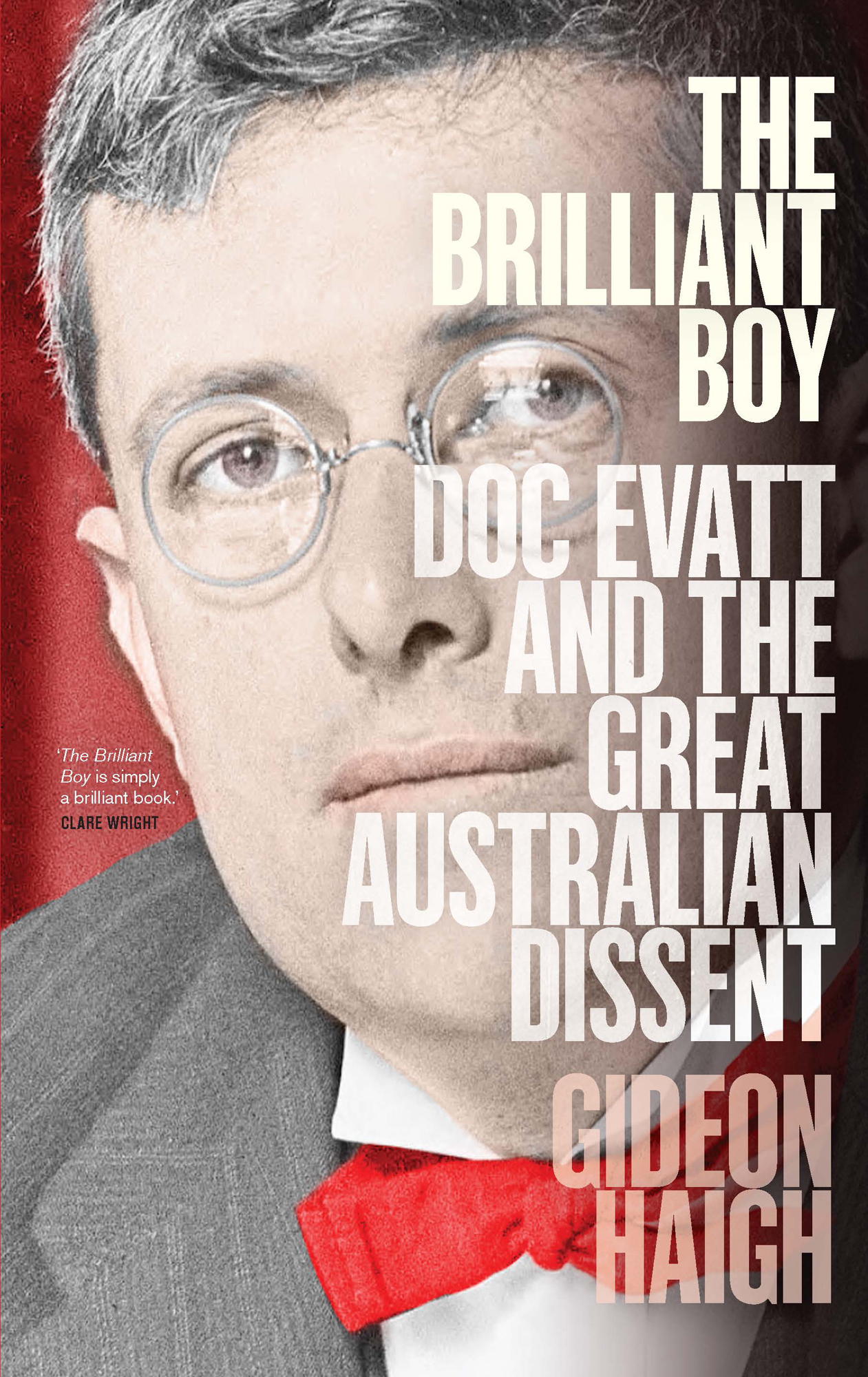

The Brilliant Boy

Doc Evatt and the Great Australian Dissent

Gideon Haigh

The Brilliant Boy is simply a brilliant book.

CLARE WRIGHT

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Join our mailing list to get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

In early 2019, I was poring over the transcript of a 1938 hearing in the New South Wales Supreme Court when a name jumped out. Kenneth McCaffery was the eight-year-old son of a tram conductor from Cowper Street, Waverley. Understandably overwhelmed by the bewigged counsel and judge, he had quickly dissolved in tears and been excused. But what little he imparted contained the last glimpse of a figure whose accidental death had precipitated one of the most complexly divisive and historically significant cases to work its way through Australias High Court.

Today we take for granted that trauma is real and that mental suffering can be as injurious as physical suffering. Eighty years ago, attitudes were different, overlain by codes of restraint and stoicism. The townscapes of Australia were festooned with evidence of national loss the memorials testifying to the ravages of war, of male casualty and female bereavement. But these were for commemoration and contemplation. In the day-to-day, one got on, one coped. The law was especially sceptical. It wanted injuries with satisfyingly visible wounds and lesions before it would consider compensation. Until one day, ajudge, in an act of legal daring that infuriated colleagues, stopped to ask: what could be more real than a mothers loss of a child?

So, McCaffery, McCaffery had there not been a rugby league player of that name? Why, yes, there had a centre for Easts and Souths who had played a dozen Kangaroos games. Could this McCaffery in the witness stand, I wondered, be that McCaffery of the football field? The footballer, I learned, had become a publican, raised ten children with his wife, and would now be in his ninetieth year. But so far as anyone knew, he was still alive, last heard of in coastal retirement. I made some calls among sporting contacts, obtained a telephone number and, with a deep breath, dialled it.

The phone rang twice; the connection was surprisingly quick; the voice, elderly but still firm, identified its owner as Ken McCaffery. When I gave my name, he companionably addressed me as mate.

Mr McCaffery, this may sound like a strange question, I began tentatively. But do you remember a boy called Max Chester?

There was a pause. I briefly thought we had been disconnected. Then the voice returned, quiet and sombre. Mate, said Ken McCaffery. Im going to start crying now

A boy called Max Chester: second from left, back row.

Introduction

This was no country for us. She saw nothing but sorrow ahead. We should lose everything we possessed; our customs, our traditions; we should be swallowed up in this strange foreign land.

Judah Waten, Alien Son

Saturday 14 August 1937 dawned cool but bright in Sydney. It came as a relief. Thursday had been drenched with rain, metropolitan areas recording average falls of 25 millimetres. Friday had then been swirled in heavy fog, causing cars and trams to collide on slippery roads and ferries to honk warily. With the weekend, bathers were drawn back to Bondis famous beaches, where some men entering the surf surreptitiously lowered their trunks to the waist in defiance of local ordinances. The playground of the Pacific expected play within certain standards. The beach patrol had recently booked a young communist activist not for the subversiveness of his handbills but for the misdemeanour of wearing only khaki shorts.

Nor did everyone experience the lure of the sea. Tucked off Bronte Road in Waverley, Allens Parade seemed to epitomise suburban tidiness: apartment blocks, bungalows, a smattering of Moreton Bay figs, a solitary telephone box. And on the ground floor of number 7, Dargo Flats, into which they had moved a fortnight earlier, Chaim and Golda Chester were shy of the sand, the water, the kitsch of the beachfront, the frivolity of the Pavilion they had barely come to terms with their adopted surname. To themselves, they remained the Sochaczewskis, part of a Polish family who had chain-migrated to Australia over the preceding decade.

The Sochaczewskis went back generations in Lowicz, a market town near Lodz in the former Pale of Settlement. Then, in 1927, after a family conference had agreed that Poland was no longer a hospitable home for Jews, they visited the British legation in Warsaw. Australia, it was agreed, was a promising destination partly for being far away, partly because nobody knew anything about it. Chaims older brother Menachem Mendel, a former Polish army private, had been first to make the journey; in Sydney he had adopted the name Max Chester by opening the telephone book at random. He applied to naturalise and married another Jewish migrant, Pesa Hillman: their firstborn, Esther Lena, signified the familys commitment to a fresh start.

Gradually, Maxs parents Nussen and Perel, and siblings Yehavat, Esther Miriam, Razel and Moshe had followed the same route, all anglicising their names also. At last, Chaim had arrived in Australia aboard the Otranto in October 1935, joining Max in the family trade of jewellery and watchmaking in Sydneys Pitt Street; Golda had shipped on the Ormonde fourteen months later, with the three children who haloed her in the family passport photograph. In Lowicz, they had been Moishe Dov, Razel and Menachem Mendel. In Waverley they became, respectively, fifteen-year-old Benny, twelve-year-old Rosie and seven-year-old Maxie.

Bondis patriotic identification with lifesavers and surfers coexisted with neighbouring Waverleys status as a residential enclave for some of Sydneys 10,000 Jews. Waverley itself was named for the mansion erected a century earlier by the Jewish theatre impresario Barnett Levey, first in Australia to stage Shakespeare. Consecration of the Eastern Suburbs Central Synagogue at Bondi Junction in March 1923 had been followed by the establishment of a Hebrew school and the Mizrachi congregation, their doings dutifully reported in Sydneys Hebrew Standard. Yet green-eyed Golda, a five-foot, forty-nine-year-old wisp of a woman, struggled to settle. In their hometown of Piotrkow Kujawski, population about 1000, her family the Gradowskis had been of account; they had held public offices, owned businesses, even the shtetls local bus. Here the buses, cars, trams and ferries whizzed through a city populated by nearly 1.4 million. It was so big, so hot, so loud. Her children took readily to Australia, their local schools and haunts: Benny and Rosie were healthily boisterous, Maxie quieter but academically bright. Chaim was comfortably grooved in his jewellery work, reinforced by siblings. But for a quiet, respectable, pious woman who kept kosher and the customs of ritual bathing, these were harsh shores.

Not every Jewish arrival remained, in fact. A year earlier, Pesas sister Ethel had soured on Sydney and returned to Poland. Golda had not that option her place was with her husband. So the marriage of the Sochaczewskis was becoming the coexistence of the Chesters, like that of the parents Judah Waten would describe in