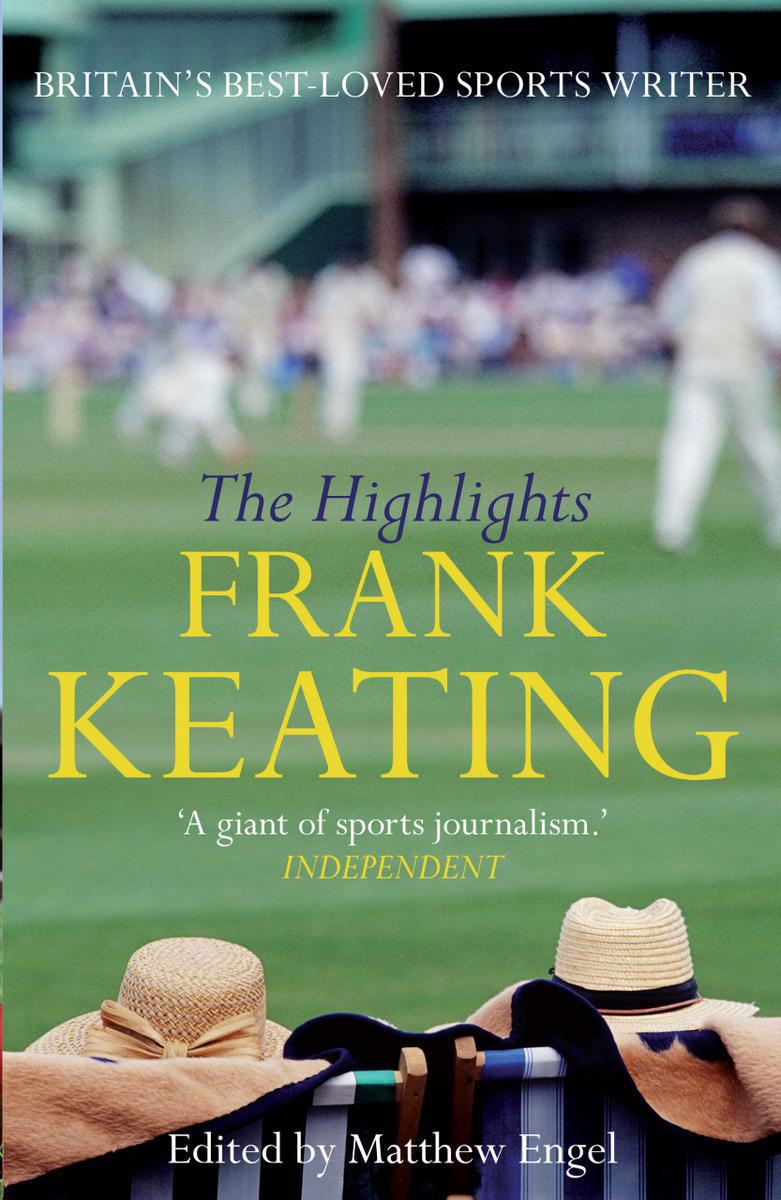

THE HIGHLIGHTS

Frank Keating

Edited by Matthew Engel

To the Keating family,

especially Jane, Paddy and Tess

The world is not amazed with prodigies of excellence, but when Wit tramples upon Rules, and Magnanimity breaks the chains of Prudence.

Dr Johnson

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The death of a newspaperman, especially one well past the peak of his celebrity, does not normally attract much public grief. But when Frank Keating died in January 2013 it was different. One experienced colleague called it an outpouring of something a bit more than respect and affection, more like gratitude and love.

His funeral, on a chill winters day, caused a spike in the number of passengers on the sluggardly line between Paddington and Hereford. On a summers night six months later a full house crammed into a hall at London University to celebrate his life. Many old friends were there, but most of that crowd had never met Frank. They were readers, mainly Guardian readers. They felt they knew him simply by reading his columns over the years.

Keatings sports writing in the Guardian spanned half a century, from 1962 to 2012. His first article was an anonymous hockey report, commissioned from him as the nearest keen young journalist on hand in Slough. There is still a little more to come: a couple of obituaries commissioned in advance still lurk in the Guardian computer system, awaiting their day.

For 40 years he kept writing: not far off 3000 Guardian articles, maybe two and a half million words. There were 14 books and well over 1000 magazine pieces: at different times he had regular columns in Punch , the Spectator and the Oldie . His last few newspaper pieces, before his final illness, appeared not in the Guardian , but its Sunday sister the Observer .

Journalistically he was a late developer: Keating was in his late 30s by the time he sprang into the Guardian sports pages and emerged, fully-fledged, as its star columnist. He began to lose his appetite for rushing around the planet after he moved back to Herefordshire in his 50s and his travelling tapered off rapidly after his health started to deteriorate in his early 60s. His rise was meteoric and in one sense he blazed across the sky, just like a meteor, only briefly.

But he packed a lot in. And the love affair between Frank and his readers was an enduring one. There were, I think, three reasons for his success. Firstly, there was his writing. It was only when I began to research this book that I began to understand that his truncated formal education was fundamental to his journalism. As Winston Churchill said of Harrow, his education was interrupted only by his schooling. And like Sir Neville Cardus 50 years before him, he marched into the Guardian , always a paper full of posh-university men, and, with barely an O-level to his name, wrote them under the table. He didnt seem to know how things werent meant to be done.

His imagery was breathtaking and vocabulary audacious: he was indeed the onliest Frank. This extended to his choice of subjects too. Daily journalists are essentially herd animals: contrary to popular belief, the main aim of a days work is not the fraught business of scooping the opposition, but to avoid being scooped editors get angry only if you miss something. But Frank would head in directions no one else had thought of: up in the morning to see Mother Teresa in Calcutta or the fortune teller in Bangalore; lunchtime with the French rugby team on Eurostar; late at night to watch Geoffrey Boycott, disc jockey. All recorded in these pages.

Secondly, there was his charm. He liked sportsmen (a rarer quality among sports journalists than you might think) and they took to him and trusted him. He made lasting friendships with them, often improbable ones: the convivial Frank hit it off with the stoical and abstemious Graham Gooch as he did with his more regular bar-companion, Ian Botham. It is true (and the great Cardus had a similar habit) that the quotes he extracted were inclined to sound a bit, well, Keatingesque. But I never heard anyone actually complain. He never misrepresented anyones thoughts; he just made them more eloquent.

As Mike Atherton pointed out in a characteristically perceptive piece in the Times , this would be impossible nowadays. In the major sports, press and performers are rigidly segregated; there is minimal contact, controlled by public relations officers. The drivel that results, Mike might have added, is not just bland and boring, but though accurately transcribed inherently falser than Franks cavalier interpretations.

The third and most important aspect is that his charm came across to the readers. They sensed that Frank was as starry-eyed and uncynical about sport as they were and shared their own delight in the personalities and their character. He was their representative at courtside, touchline and boundarys edge.

In all of that, he was the onliest. And it makes, I hope, the selection of his work that follows not just a compelling read, but also a unique record of our own sporting lifetimes.

*

I knew Frank for 40 years. I was his colleague on the Guardian for 25 of them and I was, by chance, his sort-of neighbour in Herefordshire (we lived at opposite ends of the county) for more than 20. He was a friend, something of a hero and to a large extent my mentor. His widow Jane kindly asked me to give the eulogy at his funeral. By public demand (well, a couple of people asked) this is reprinted at the back of the book, along with other tributes, in lieu of a fuller appraisal here.

Editing this anthology has been largely a pleasure, but it has posed particular challenges. At times I have felt like a scholar of Aramaic or Sanskrit, worrying away at the true meaning of some ancient fragment of text. Let me explain. To start with, Frank was not a precise every-comma-in-place kind of writer. He excelled at verbal pyrotechnics, which inevitably meant the odd damp squib (possible cause of error number one in this collection).

Most of his career took place using the old newspaper technology (not that he ever mastered computers). Newspaper reports were dictated by telephone to copy-takers, a profession now, alas, just about extinct. Nearly all were gloriously eccentric; some were brilliant, some were not. One on the Guardian was deaf (possible cause of error number two). Then there were the sub-editors, of whom I was once one. Mainly, we corrected the writers errors of grammar or fact; being human, we sometimes added our own instead (3).

On the Guardian , the edited copy would be taken down to the basement by a chirpy Cockney messenger to be rekeyed into hot metal by a typesetter (4). The old Linotype machines did not allow the setters to correct mistakes; what was done was done. Of course, there were proofreaders to deal with this. But the Guardian printing presses were several streets away from the office and the corrections often failed to arrive in time (5), which is why the Guardian became infamous for its misprints and rechristened the Grauniad . Also, there was no precise means of assessing in advance whether the copy was the right length for the space available. If it was too long the metal type itself had to be cut by a compositor under the direction of a sub-editor, very, very fast. Both parties were capable of mistakes (6 and 7). Sometimes paragraphs would appear in the wrong place or transposed and a story might well end in the middle of a sentence for no apparent