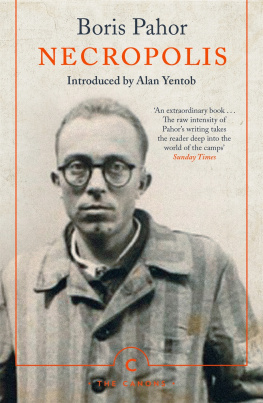

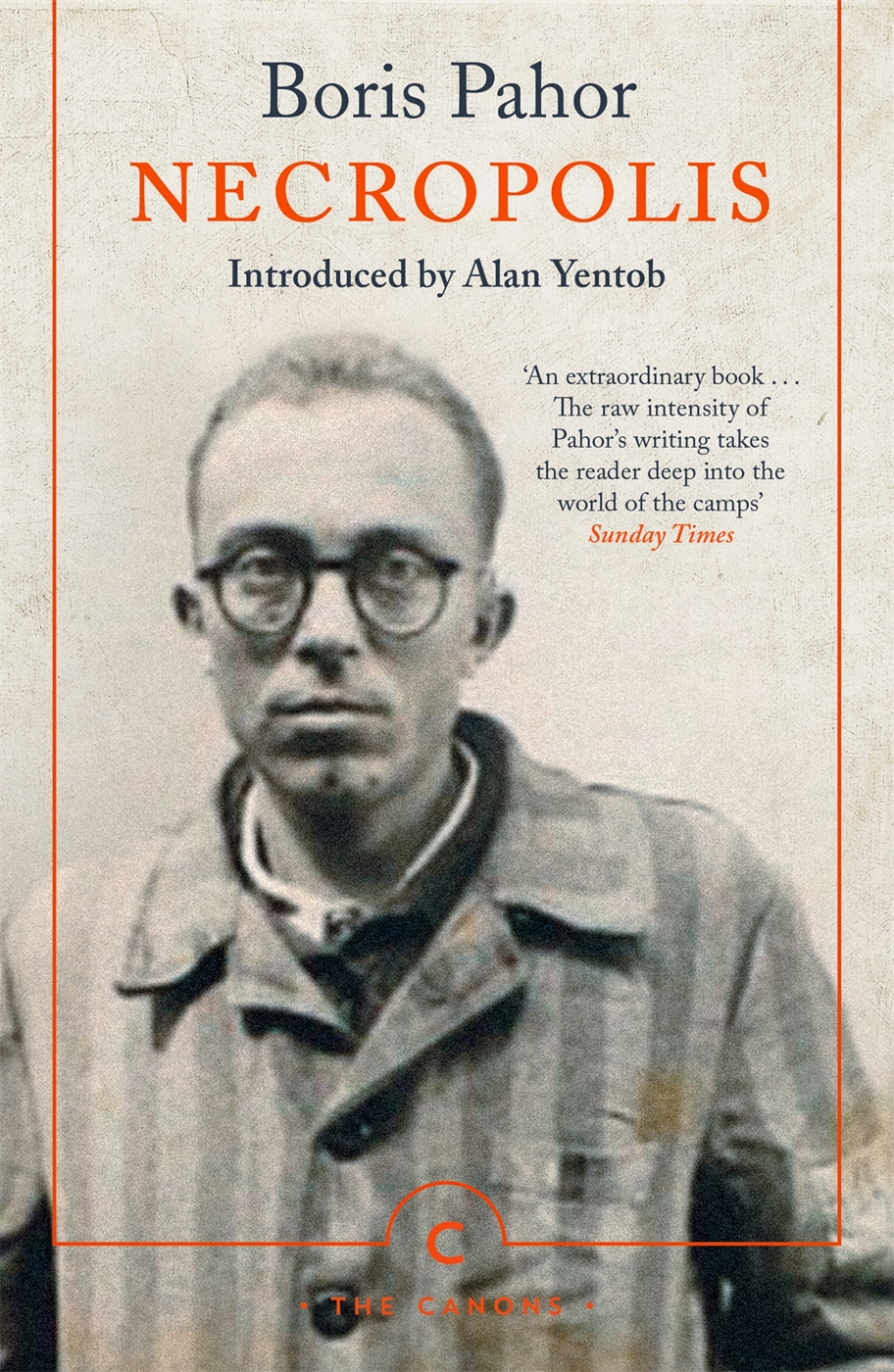

Boris Pahor is a member of the Slovenian national minority in Italy, and is considered among the greatest living writers in the Slovenian language. Several of his works portray the experiences of World War II concentration camp prisoners, and their attempts to reintegrate into everyday life after the war a process Pahor, a Dachau survivor, personally experienced.

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Canongate Books Ltd,

14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

Originally published in Slovenian as Nekropola by Zalozba Obzorja Maribor, 1967

canongate.co.uk

This digital edition first published in 2020 by Canongate Books

Copyright Boris Pahor, 1967

English translation copyright 1995 by Harcourt Brace & Company

Introduction copyright Alan Yentob, 2020

The right of Boris Pahor to be identified as the

author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on

request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 83885 229 0

eISBN 978 1 83885 230 6

Cold ashes lie over the shadows.

SREKO KOSOVEL

Contents

INTRODUCTION

S eventy-five years ago, in November 1944, American soldiers arrived at the gates of a Nazi concentration camp, high up in the Alsace mountains, in a part of France annexed to Germany.

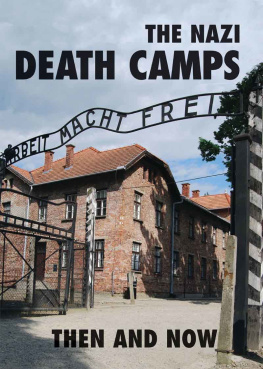

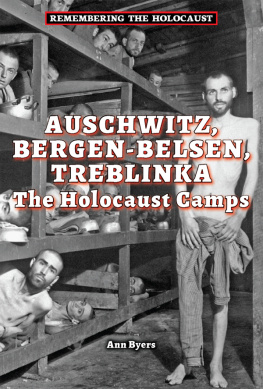

Once a popular winter holiday resort, Natzweiler was the first Nazi death camp to be discovered by the Western Allies. Although small and even now relatively unknown, it was also one of the deadliest. Nearly half of its estimated 52,000 prisoners died.

A British intelligence officer who accompanied the troops wrote a report detailing the torture, executions and medical experiments that had taken place there. He thought it would send shock waves through Allied Command, but it fell on deaf ears. There was a war still to be won and it wasnt until Auschwitz and Belsen were liberated the following year that the true horror of the camps finally became known to the world.

The name Natzweiler was quietly forgotten, but one man lives on to tell the story, and he has forgotten nothing. His name is Boris Pahor; he is now 106 years old, the oldest known survivor of the Nazi concentration camps. He was a prisoner in Dachau, Belsen and Natzweiler, where he returned twenty years later to write his extraordinary book: Necropolis City of the Dead.

The raw intensity of Pahors writing takes the reader deep into the world of the camps. It stands equal to Primo Levis If This Is a Man. Necropolis has been published across Europe to great acclaim but has yet to reach the wider English-speaking audience it deserves, until now.

I first heard about the book and its author thanks to the determination and insistence of my friend and colleague Marc Ramsay, and together we eventually made our way to Boris Pahors home on a hillside overlooking Trieste, in Italy. Soon after our arrival Pahor vividly recalled the moment of his arrest by the Gestapo in the city square: They started to beat me with a leather strap, each with a whip, all over my body. I was screaming. I was like a zebra when I went back to the jail.

He was a partisan member of the Resistance, a loyal representative of the Slovenian minority, determined to oppose Italian fascism and the Nazi takeover of his homeland. His SS captors locked him in a cell no bigger than a cupboard for twenty-four hours. He was convinced he would suffocate. If I lost consciousness, I would pass away and I would be taken out dead, he told me. But Pahor didnt die. Instead of killing him, the Nazis sent him to Dachau. That journey, he says, was the beginning of a descent into the heart of darkness. They labelled you with a red triangle. You were given a number that replaced your name. You were thrown trousers, a jacket, a pair of clogs. But despite the clothes you were almost naked. It was very cold, several degrees below zero.

Reduced to a number, Pahor ended up in Natzweiler, the camp where he was to stay the longest. It was constructed high up on a mountainside, which was once a fashionable ski resort. A grand holiday home with a swimming pool was requisitioned for the camp commandant and his young family; ashes from the crematorium were used to help grow their flowers. The local restaurant and hotel now housed SS officers. The village dancehall was transformed into a gas chamber.

In Natzweiler you were always afraid, says Pahor. You came in at the top and the gallows welcomed you. Looking down the steps you could see the barracks. We were told there was an oven there. There was no way out but the chimney.

The camps perimeter was secured by a double fence of electrified barbed wire. The sentry boxes searchlights were always on. Unlike in the bigger camps, there was nowhere to hide.

It was impossible not to think of the crematorium as you constantly saw it, Pahor told me. You couldnt avoid the smell of burning flesh because you had to keep breathing, so in a way you became part of that burning flesh.

He was still a child when his beloved Slovenian community centre in the heart of Trieste was burned to the ground by fascist extremists. I did not know what the end of the world was, he told me. But as a boy of seven years old, it was the end of the world for me.

Now he realised those flames that haunted his childhood had followed him, and all Europe was ablaze.

Natzweiler was intended for prisoners of war, political prisoners and members of the Resistance, but there was also a small minority of Jews, gypsies and Jehovahs Witnesses. The prisoners transported there were used as slave labour, initially working in the nearby quarry, cutting pink granite rocks that would eventually be used to face the Nazis showpiece buildings. As the war went on the prisoners were forced to work in underground factories to support the Nazi war machine by manufacturing parts for aircraft engines. Survival was perilous: typhus, fatigue, hunger, freezing cold. I asked Pahor how he managed to survive. He raised his little finger. This is what saved me, he replied.

Boris had injured his finger while working in the camp and kept it covered with a paper bandage to ward off infection. It turned out to be a lifesaver. When it was his turn to be examined, the camps doctor learnt that Pahor understood several Slavic languages and spoke Italian, French and German. He was assigned duties as a translator and medical orderly, where he tried to make the lives, and slow deaths, of his fellow prisoners as comfortable and humane as possible. There was little or no medicine and even less food.

During the winter months, icy winds drove temperatures down to minus 20C. The prisoners thin, striped clothing was no protection from the cold, but there was an occasional respite when they were sent to the shower block in an effort to avoid an outbreak of typhus in the camp. We had to undress so that we were completely naked. They shaved our heads, armpits and crotches. There was not a hair left on our bodies. Then they put us under the showers. What he writes about this in