Copyright Norman Webster, 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written consent of the publisher.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication data available upon request.

978-1-988025-55-1 (hardcover)

Printed in Canada

Publisher: Sarah Scott

Book producer: Tracy Bordian/At Large Editorial Services

Cover design: Lena Yang

Interior design and layout: Liz Harasymczuk

Copy editing: Wendy Thomas

Indexing: Wendy Thomas

Proofreading: Eleanor Gasparik

For more information, visit www.barlowbooks.com

| Barlow Book Publishing Inc.

96 Elm Avenue, Toronto, ON

Canada M4W 1P2 |

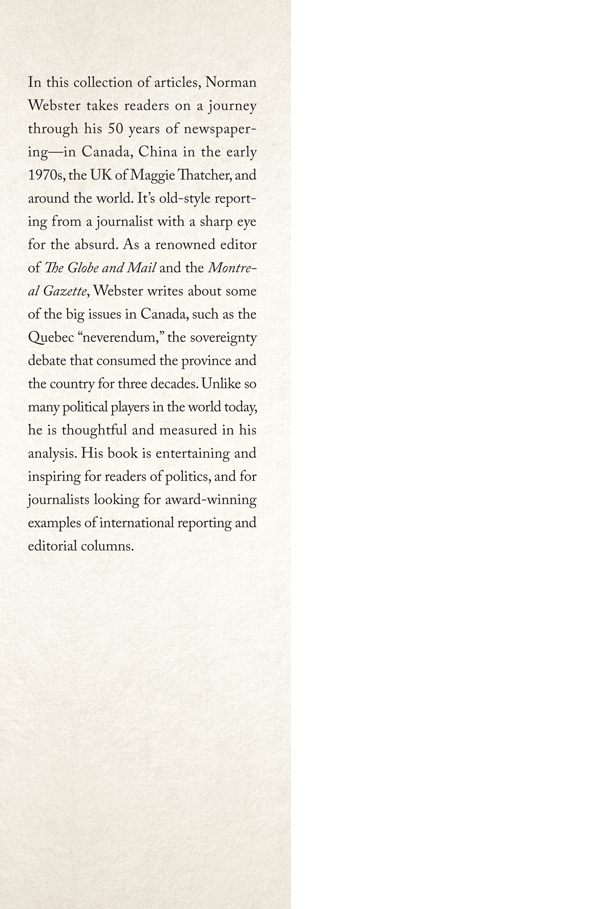

FOREWORD

by John Fraser

Along and even distinguished career in journalism does not necessarily make you a more prescient observer of what lies ahead, but experience does make you wiser and unlikely to succumb to the lower realms of reportage. It also makes you incredibly useful for observing the realities of the day. The career of Norman Webster took the usual twists and turns a generalist journalist of the last half of the 20th century was heir to, and he came to it initially from a position of privilege (his uncle owned The Globe and Mail). So the singularity of his achievement is something of note, for few have been so clear-sighted about delineating the times they lived in and through.

Apart from having an advantageous foot in the door, that achievement had nothing to do with privilege or even the hilarious range of his assignmentsfrom Toronto night police to Politburo shenanigans in Communist Chinaand everything to do with a dedicated righteous integrity to report what he actually saw. Consequently, if he managed to avoid platitudes in his writing, Norman Webster nevertheless embraced the single most honourable platitude of his profession because nothing you will read in this collection of a journeymans observing and reporting for over five decades was done out of fear or favour.

I do not think in a lifetime acquaintanceship I ever detected an ounce of cynicism in the man. He came to everything with a simple sense of missionto tell a good story honestly and with enough flair to hold a readers attention. Although he had a knack for an apt phraseand you will see many throughout this collectionhis style and journalistic philosophy have always been lean.

The trajectory of the career began in his beloved Eastern Townships of Quebec and most likely will end there. The journey all along the way has been as steady as it has been remarkable, and these junctures are all beautifully delineated in this collection of his finest journalism. In Toronto at Queens Park, in Ottawa or Montreal, in the United Kingdom or the Peoples Republic of China; at a beat reporters desk, in a foreign bureau, on the road or in the air or on the water; at Parliamentary Press Gallery dinners, or the Great Hall of the People, or down a dusty street in Cairo: wherever Norman found himself or was assigned or was just following a nose for news, the thing that keeps coming back, which actually haunts his journalism, is the fundamental decency of the man. Somehow I cant imagine him picking a fight on a hockey rink.

Any reader of this book does not need me delineating endlessly the particularities of Websters prose. The entire collection is a monument to a type of writing and reporting that is all too rare in the profession. At its best it shares a kinship with the lean and supple prose of Arthur Koestlers Arrow in the Blue or even George Orwells transparency in Homage to Catalonia. So enjoy and judge all that for yourself. What I want to clearly set out here, however, is something that is not particularly evident in this collection: he was also a prince of an editor-in-chief.

And how do you get royal status in one of the most thankless jobs on Gods earth? Norman Webster managed one short of a hat trick by presiding over the editorial menageries of both the Montreal Gazette and The Globe and Mail in Toronto. Do you have any idea what is entailed here? For all the joys of finding new talent or reviving older and perhaps momentarily moribund talent, or conceiving original election coverage, or sending Our Man in Wherever encouraging notes while Our Man is undergoing a meltdown in both confidence and writing skill, have you even an inkling of the amount of listening an editor-in-chief has to put up with?

Listening, listening, endless listening. Listening to people who are sure they could do your job far better than you are doing it, listening to the familiar whiners, backstabbers and bullies who afflict most newsrooms, biting your tongue when a publisher talks rubbish. Listening, listening, listening, and still you have to get the damn paper out at the end of the day.

Editing a great daily requires a species of courage disappearing along with the great dailies themselves, and one of the joys of this collection is being in the writerly company of a supremely confident, erudite editor who has literally seen it all and still embraces a broad humanity that is the hallmark of the best journalism of the 20th century. To have known Norman Webster, to have worked with and for him, was to understand what Thomas Paine was said to have claimed long ago: that journalism helps us see with other eyes, hear with other ears, and think with other thoughts than those we formerly used, and to be the better for it.

INTRODUCTION

This book is mainly a collection of columns. Writing them was a glorious grind, the most satisfying years in half a century of journalism pursuing The Story.

Pundits? Columnists? The guys who come down from the hills to shoot the wounded, say the cynics dismissively. Pshaw. Trust me; writing a column at full stretch on a Friday afternoon for the weekend paper is as exacting and worthwhile an endeavour as any on Gods green earth.

Which brings to mind great days, especially at the Montreal Gazette and the Toronto Globe and Mail, which paid the freight for most of these sketches. My paramount boss, Dic Doyle, the late editor of the Globe, always saw himself simply as a newspaperman, an old-time hack with printers ink in his veins, and he was always searching for emulators. I was one of those young reporters lucky enough to get our first big break because he saw something in us. My own good fortune was being sent to Quebec City in 1965 to cover the antics of Jean Lesage, Ren Lvesque, and other performers in the blare of the Quiet Revolution. This led to illuminating assignments, far and wide, when the miracles of transmission allowed a correspondent to file his copy across deserts and oceans to home base. Gone are the not-so-good old days of tapping out telex tape in the basement of an African hotel or the horrors of the Cairo cable office.

Nowadays, there are further miracles. The story is done, the button pushed, and its ready for direct transmission into modern homes. No more flipping coins for first crack at the phone booth on a dark road in rural Quebec.