William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2016

Copyright Philip Webster 2016

Peter Brookes cartoons Peter Brookes

Photograph in Introduction Dave Bebber/The Times

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the author and publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any future editions.

Philip Webster asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover image David Bebber for The Times

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008201333

Ebook Edition September 2016 ISBN: 9780008201340

Version: 2016-09-20

To my late sister, Kay, for encouraging me to become a journalist, and to Sally, for encouraging me to write this book.

Contents

Life is full of chances. A chance visit to The Timess office at Westminster on a Tuesday in July 1972 led me to an adventure lasting more than four decades which finally ended in January 2015, after my 15,932nd day as an employee of the worlds greatest newspaper. I am lucky to have been part of a small chunk of its 230-year history.

In those days The Times had far more reporters in Parliament than any other paper and gave far more column inches to coverage of parliamentary affairs. Unlike many other papers, it had its own office, known as The Times Room. I walked into The Times Room on that July afternoon during a tour round the House of Commons. I was a subeditor on the Eastern Evening News in Norfolk, and Tuesdays happened to be my day off. I had been to the office of the Commons Official Report, known as Hansard, next door and the editor kindly took me to meet the head of The Timess parliamentary staff, Alan Wood. It being a Tuesday, Prime Ministers Questions were about to happen. In those days it was two fifteen-minute sessions on Tuesday and Thursday. Alan gave me a notebook and took me into the gallery, asking me to have a go at recording the exchanges between Edward Heath and Harold Wilson. I had good shorthand, which Alan could see, but my efforts at reading it back were patchy to say the least. In any case there were no jobs going.

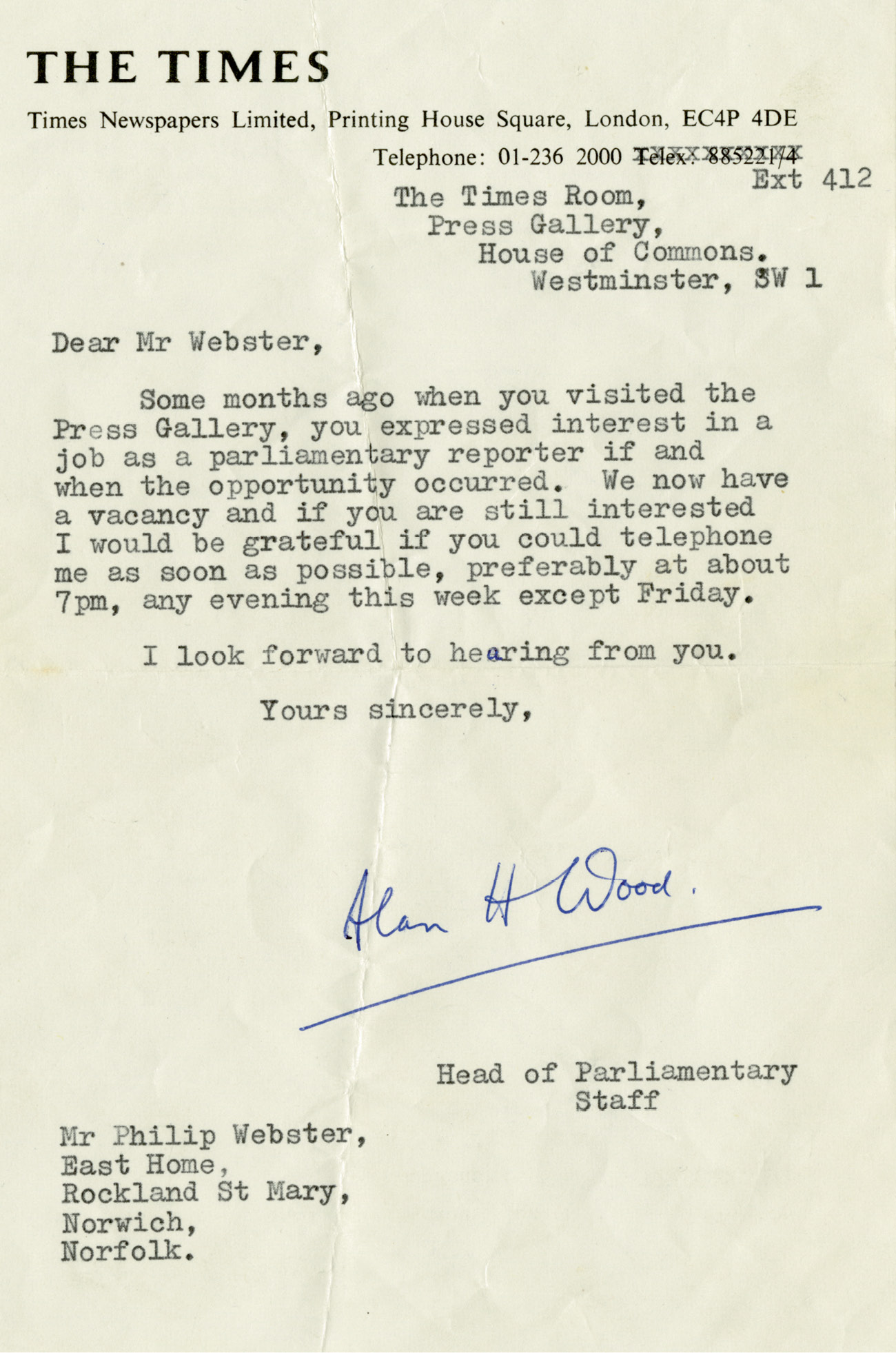

Four months later I received a handwritten letter from Alan telling me a vacancy had arisen and asking if I would be interested. I went down to the Commons again in mid-January. It was again on a Tuesday and my left arm was in a sling after a football injury that Saturday. The cynics in the office smiled to themselves, thinking I had come up with the ultimate alibi for a failed test in the gallery. Fortunately, Im right-handed.

Alan Wood put me through the same process and, this time, knowing what to expect, I made a good fist of it. He asked me to head down to Printing House Square at Blackfriars, then the home of The Times, where I was interviewed by John Grant, the managing editor. He was at the time president of the National Council for the Training of Journalists (NCTJ) and it helped a lot that I had been on one of the NCTJs pioneering full-year courses, and had secured the NCTJ diploma at the end of my training period. He offered me a job and I bit his hand off. It was the biggest decision of my life but it was not at all difficult.

Forty-three years later I have written this account of my career covering politics for The Times. It does not pretend to be a political history of the period. Enough biographies and autobiographies have been written to do that job many times over. But I have found myself at the centre of most of the big stories of the last thirty-five years the fall of Labour in 1979, the rise and fall of Margaret Thatcher, the emergence and fall of John Major, the rise and fall of Tony Blair and his wars with Gordon Brown, the aftermath of 9/11, the war in Iraq, the fall of Brown, the rise and rise of David Cameron, and the shock election of Jeremy Corbyn. This is my take on some of the big things that happened, and how I covered and unearthed them.

Being a political correspondent of The Times, including eighteen years as its political editor, has given me a ringside seat at the most dramatic political events of the last quarter of the twentieth century and the early years of the twenty-first. Although my predecessors have probably felt the same and despite having no illusions myself this to me has seemed like a golden era of political journalism and I am lucky to have been part of it. During all those years I was a member of the Westminster Lobby, whose merits or otherwise I deal with later.

It was a position that gave me ready access to politicians of all parties and I got to know them well, including four prime ministers, any number of Cabinet ministers and countless back-benchers, as well as the hundreds of officials and advisers who support the ministers and their shadow ministers in their jobs.

It was a role that gave me the opportunity to travel the world a rough calculation puts my total air miles in the service of The Times at close to the million mark as well as a seat in the Commons Press Gallery at every significant event. I was there the night Michael Heseltine brandished the mace, the night the Callaghan government fell, the day Sir Geoffrey Howe brought down Margaret Thatcher, the days she and Tony Blair said farewell, the night MPs voted for war in Iraq, and for every Budget and autumn statement for forty years.

Occasionally it was a role that landed me in the most unexpected, even dangerous, scrapes. But most of it was fun, and if the reader does not get the impression after reading this that I had a very good time I have failed in my task.

It was also a position of huge responsibility, something of which I was well aware and about which I sometimes worried. The political press clearly has an important role in holding politicians to account. But what we write shapes events and makes or breaks careers, including those of party leaders. A few reporters have gone on to work for political parties but the vast majority are not players. Most political correspondents have no allegiance to a party. I never have or will but I have good friends in all the parties. The reader may find this strange, but in the tens of thousands of conversations I had with politicians while I was a senior political correspondent, not one asked me how I voted. I imagine they felt that as an impartial reporter I would have been insulted by the question, but I would have had an answer: I did not vote during those years.

Political correspondents are without doubt an integral part of the political process. It places a severe duty on us to get our stories right, ensuring they are fair, accurate and impartial the mantra that is drummed into us from our first day in journalism school. When I appeared before the Leveson Inquiry into press standards in 2012, one point I tried to make very firmly was the importance of separating fact and comment in newspaper coverage, a line that has occasionally been blurred in recent years.