Thatcher and Sons

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

A City at Risk

Landlords to London

Newspapers: the Market for Glory

The Companion Guide to Outer London

Images of Hampstead

The Selling of Mary Davies

The Battle for the Falklands (with Max Hastings)

Accountable to None: the Tory Nationalisation of Britain

Englands Thousand Best Churches

Englands Thousand Best Houses

Big Bang Localism

SIMON JENKINS

Thatcher and Sons

A Revolution in Three Acts

ALLEN LANE

an inprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

ALLEN LANE

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Mairangi Bay, Auckland 1310, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published 2006

Copyright Simon Jenkins, 2006

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

EISBN: 9780141911090

Contents

PART ONE

The Revolution in Embryo

PART TWO

High Noon

PART THREE

The Fall

PART FOUR

Deceptive Interlude

PART FIVE

The Blair Project

PART SIX

Blatcherism Ascendant

PART SEVEN

The Third Revolution

Acknowledgements

My interest in politics began when I worked on a project for the Redcliffe-Maud commission on local government in 1970 and in travelling and talking to people in every corner of the United Kingdom ever since. The conclusions of this book are the outcome of that experience and as a columnist for The Times, Evening Standard, Guardian and Sunday Times.

My sources are reflected in the notes and bibliography. Conversations and interviews with participants are mentioned where appropriate. I would like to thank Stuart Proffitt of Penguin, who has been a spur and encouragement through the project. Others who were generous with stimulus, advice or argument include Leon Brittan, Robin Butler, Christopher Foster, Jonathan Freedland, Peter Hennessy, David Howell, Martin Ivens, Kate Jenkins, Jeffrey Jowell, Tim Lankester, Andrew Likierman, Nick Raynsford, Adam Ridley, Richard Ryder, Andrew Turnbull, William Waldegrave and David Willetts. I acknowledge the groundbreaking work of David Marquand, Gerry Stoker and Anna Randle on localism. Tony Travers has been a constant source of inspiration and advice. He and my assistant, Charlotte Dewar, read and commented constructively on the text.

Introduction

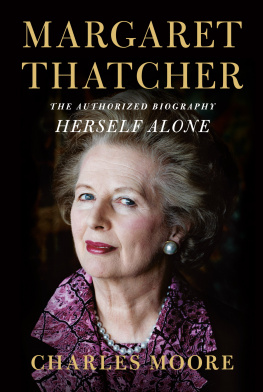

Margaret Thatcher was Britains most famous prime minister since Churchill. Over eleven years she transformed her nation and gave birth to an -ism in use to this day. She was not widely loved, but she was admired even by those who disagreed with her. Her Conservatism was controversial, yet it showed that democratic leadership could both prescribe and administer unpopular medicine and win elections in doing so.

A quarter of a century is a good span of time from which to re-examine any historical movement or event. Thatcher was a truly revolutionary leader. She was dissatisfied by what she saw round her and set herself to change it utterly. She saw socialism and wanted the opposite, freedom from the state. She was no conservative, other than in an emotional attachment to a certain sort of Britishness, but proselytized ceaselessly for change. In the process she bred a generation of politicians all of whom took her as their reference point and all of whom dedicated themselves to the cause of reform. Unlike most radicals who end by running before the wind of events, merely nudging an occasional course correction, Thatcher headed straight into oncoming gales. Though her form of economic liberalism was not new, her will to implement it against the grain of politics was unique. Hers was never going to be a quiet revolution.

The test of any revolution is, did it work and did it last? When on 20 November 1990 Thatchers cabinet colleagues trooped into her Commons room and told her to go, the world gasped. What had they done? The answer is that they had decided that Thatcherism could best be preserved if its progenitor were removed from the scene, and they were right. After the fall, the legacy was carried forward by John Major, Tony Blair and his powerful Chancellor, Gordon Brown, to become the ruling consensus of British government. These three men, Thatchers sons, were convinced disciples, going where even their mistress had feared to tread. She treated them, with varying degrees of faith, as her heirs. For more than a quarter of a century Britain was in the grip of a concept of government at first wholly untried but soon established and exported round the world. Such milestones in a nations history are rare.

I witnessed the Thatcher era from the start. I worked on the fringes of the Conservative party before the 1970 general election as it sought a new direction in Opposition under Edward Heath. Harold Wilsons 1964 Labour government, of which so much had been hoped, was a disappointment. The post-war welfare consensus known as Butskellism (after the Tory, Rab Butler, and Labours Hugh Gaitskell) was in disarray. The economic ideas underpinning Thatcherism can be found in embryo in debates in the 1950s and 1960s, first in the Institute of Economic Affairs and increasingly within the Conservative party itself and in such think tanks as the Bow Group. At the time they were espoused by a minority. Conservatism was still essentially what it said, a reluctance to depart radically from the ruling consensus, even when it was that of post-war welfare socialism.

Heaths undoubtedly radical ambitions, many of them proto-Thatcherite, did not long survive his arrival in Downing Street, dying in the industrial chaos of 19734. A year after the partys early exit from power came the backbench putsch that brought Thatcher to the leadership. The then Labour governments of Wilson and James Callaghan proved, for the last time, that the prevailing view on how to manage the economy did not work. British politics was seldom so miserable as between the IMF crisis of 1976 and the winter of discontent of 1979. The nation seemed lost to defeatism and its government to impotence. Editorials referred hopefully to the spirit of Dunkirk as if history might yet replay 1939 and after. But the much-debated British disease seemed incurable.

Like most observers at the time, I at first viewed Thatchers Tory leadership as transitional, a rightist rebellion, possibly shock therapy, probably a mistake. The Heathites, reverting to Butskellism, would somehow resume control. Thatcher had come to power at the head of a peasants revolt and did not seem a natural leader, let alone a prime minister. Her voice was shrill and her manner hectoring. She was a bad listener and responded to any suggestion with a cantankerous right-wing tick. Her four years as leader of the Opposition were unhappy for her and for her party, and her early years in office hardly less so. Thatcher before the Falklands War of 1982 never seemed other than a passing phenomenon.

Next page