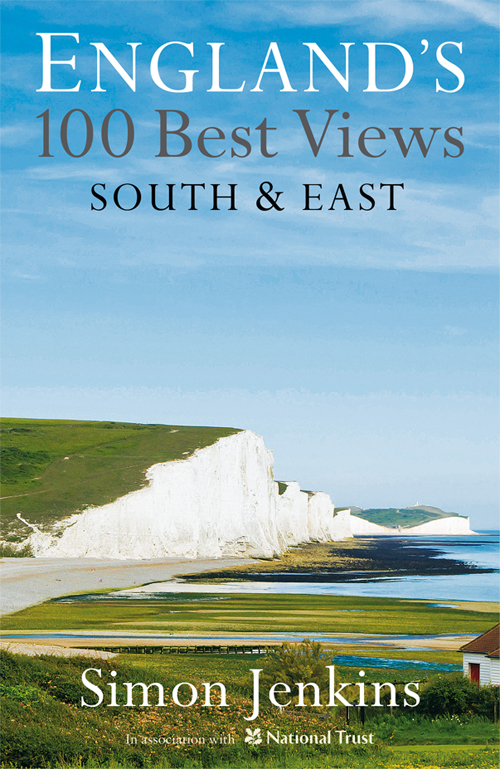

ARUNDEL

From Crossbush

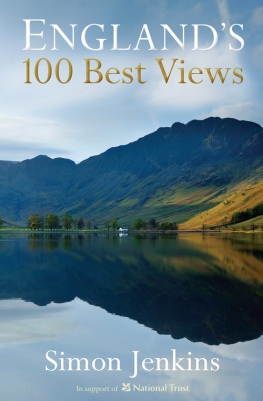

Grey, sombre Arundel lies on the flank of the downs like a cat waiting to prey on the valley below. In the Sussex volume of Pevsners Buildings of England Ian Nairn declared it one of the finest town views in England, though he reflected mid-twentieth-century taste in complaining that this was chiefly due to the Victorians. Arundel is indeed a marriage of Middle Ages and nineteenth century, a monumental expression of the aristocratic pomp and Catholic faith of the Howards, dukes of Norfolk.

The tightly packed town at the foot of its castle appears at first more French than English, a lofty citadel on a defensible cliff on a bend in a river. But from across the fertile flood plain of the Arun from Crossbush, the scene acquires the softer outlines of Sussex and the South Downs. From here, Arundel could only be in England.

A motte and bailey castle was begun in 1067 by Roger of Montgomery immediately after the Norman conquest. It was to command the south coast and guard a crucial gap in the downs. The castle then passed down the female line of Fitzalans and Howards to become the principal seat of the dukes of Norfolk. Nothing better illustrates the flexibility of the English constitution than that the Howards should remain hereditary heads of the peerage and earls marshal of England despite being Roman Catholic. The family lives at Arundel to this day.

Arundels outer defences were demolished after the Civil War but extensive rebuilding took place under the Georgians, including the creation of one of Englands finest private libraries. The castle was drastically enlarged, in 1846 for a visit by Queen Victoria and again by the fifteenth duke in the late nineteenth century. Arundel became the Windsor of the south coast, a sequence of halls, state rooms and private apartments surmounted by battlements and fortifications. They start out from the side of the hill, dominating the town below. The castle has stood in for Windsor in films such as The Young Victoria and The Madness of King George.

Arundel: Victorian variations on a medieval theme

The adjacent cathedral is almost more prominent than the castle, built at Norfolk expense in 1868 to celebrate the Catholic emancipation of forty years earlier. The architect was the eminent gothicist Joseph Hansom, who also designed the Hansom cab. Though lacking the florid detail of most gothic structures, it is a superb stage set, rising on buttresses, transepts and pinnacles to profess its faith across the valley.

These two great buildings are attended by an immaculate small Sussex town, a packed cluster of tiled roofs and red-brick walls surrounding a high street that winds round the castle mound. The downs above extend west towards Goodwood, where the prominent racing stadium of another Sussex grandee, the Earl of March, intrudes on the horizon. To the east is the Arun gap, punched through the downs towards Pulborough.

The foreground of the view comprises water meadows so smooth they might have been rolled for cricket, interspersed with dikes and punctuated by an occasional tree, barn and church tower. The prospect is specially blessed when a mist lies on the meadow and the castle rises in the sun beyond. Victorian does not clash with the Middle Ages, but rather plays variations on a medieval theme.

ASHFORD HANGERS

Towards Steep

In the distance we can see the long ridge of the South Downs floating comfortably across the horizon. To the south the contour softens towards the coast at Portsmouth. But above the village of Steep, the hills seem to lose all discipline. The greenside ridges of the Hampshire Downs argue with each other. Escarpments bunch and jostle. Beech woods cling to the slopes in dramatic clumps known as hangers, from the Old English hangra, or wood on a slope.

It was here that the young Edward Thomas came with his family in 1906 to pursue a struggling career as a writer and naturalist. Here the American poet Robert Frost encouraged him to turn to poetry before he enlisted for the trenches in 1916 at the advanced age of thirty-eight. Thomas was a depressive who found solace in communing with his surroundings. He would run the soil through his hands and say the England he so loved was not mine unless I were willing and prepared to die in its cause. Die he did, at Arras in 1917.

The Thomases lived in a number of houses beneath and above a bend in the Ashford Chase escarpment known as Shoulder of Mutton. From here, he claimed, he could see sixty miles of South Downs in one glance. To commemorate Thomass birthday each March, the Edward Thomas Fellowship organises walks in the area, observing the folds of hill, the beech, yew and elm, the buzzards and the rich birdsong, as he did. Ashford Hangers was to Thomass pen what Flatford Mill was to Constables brush.

A land worth dying for: Thomass Ashford

The viewpoint from Shoulder of Mutton towards Steep is reached along Cockshott Lane past the gallery of the Edwardian Arts and Crafts woodworker Edward Barnsley. Next door is the Red House, one of Thomass local homes. The path passes through thick woods which narrowly avoided clearance in the 1950s and opens out through a gap in the trees. The valley floor presents a picture of clusters of woods and fields, with the downs rolling into the distance, blue-grey in the summer gloaming. Boundaries intersect in a geometry of curving lines. To left and right the hangers seem literally to hang from the slopes.

The landscape is dotted with affluent Hampshire villas. The area is known from its contours as Little Switzerland (an epithet shared with Church Stretton under the Long Mynd), though Little Tuscany might seem more appropriate. It was colonised by the Arts and Crafts movement in the early twentieth century, stimulated by the arrival of Bedales school. We can see through the trees the sloping roofs and gables of houses by Ernest Gimson, Raymond Unwin, Baillie Scott and W. F. Unsworth, with Barnsley up on the hill working their wood.

Thomas was little recognised in his life, but in 1937 John Masefield commemorated him with the Poets Stone halfway up the Shoulder of Mutton slope, looking out across the valley he knew well. The stone is, curiously, a sarsen brought from Avebury. The inscription from Thomas is typically gloomy: And I rose up and knew I was tired, and I continued my journey.

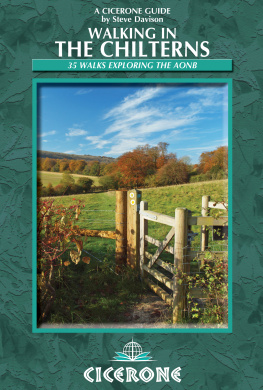

These hills have a strange atmosphere. The Hampshire hangers are unlike the comforting beech woods of the Chilterns. As Thomas sensed, they are more restless and mysterious in their evocation of nature:

The Combe was ever dark, ancient and dark.

Its mouth is stopped with bramble, thorn, and briar;

And no one scrambles over the sliding chalk

By beech and yew and perishing juniper