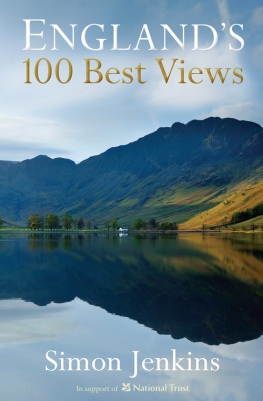

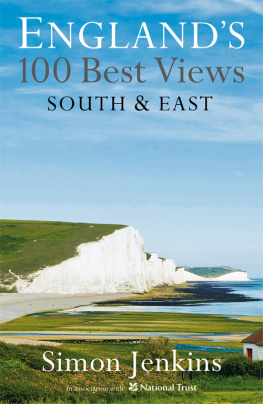

Also by Simon Jenkins

A City at Risk

Landlords to London

Companion Guide to Outer London

The Battle for the Falklands (with Max Hastings)

Images of Hampstead

The Market for Glory

The Selling of Mary Davies

Accountable to None

Englands Thousand Best Churches

Englands Thousand Best Houses

Thatcher and Sons

Wales

A Short History of England

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Simon Jenkins, 2013

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Designed by James Alexander www.jadedesign.co.uk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Butler Tanner & Dennis ltd, Frome and London

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 178125 0952

eISBN 978 184765 9484

With the exception of love, there is nothing else by which people of all kinds are more united than by their pleasure in a good view.

Kenneth Clark

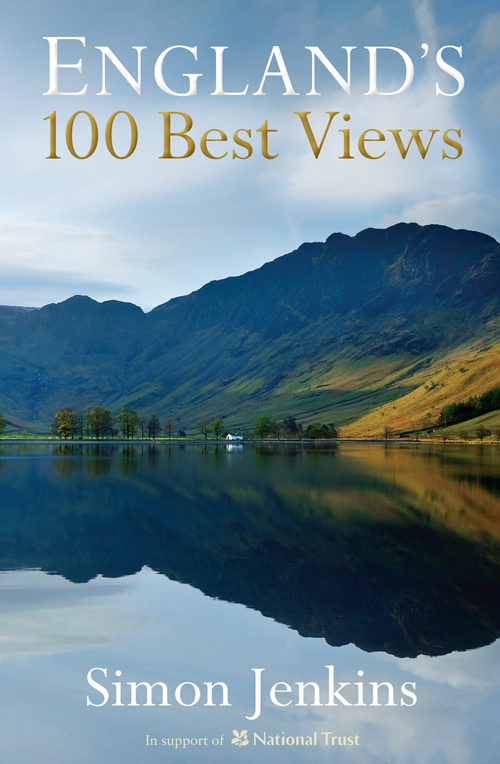

Windermere from Gummers How, Moecambe Bay in the distance

INTRODUCTION

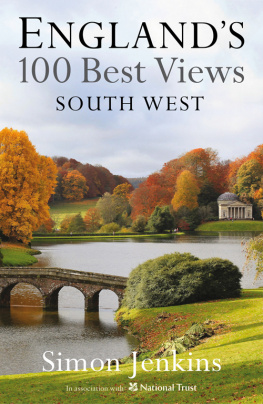

This book is a celebration of the hills, valleys, rivers, woods and fields that compose the landscape of England. I came to marvel at them while seeking out the best of Englands churches and houses. I realised that a buildings appeal is not intrinsic, but is a collage of the contexts from which it draws historical and topographical reference. They might be a churchyard, a garden, a stand of trees, an adjacent village or other buildings in an urban setting. Mostly it was just countryside. Such background became an ever more important component of my appreciation of a building, until background became foreground and I was captivated.

The English landscape is traditionally divided between town and country, the product of mankinds struggle to wrest a living from the earth over thousands of years. None of it remains truly wild, but a diminishing amount is what we call countryside, land between built-up areas that still answers to natures moods and seasons. This is the England that English people profess to love. It is among the crown jewels of the national personality.

My intention is to examine not so much the landscape as our emotions in responding to it, the impact it makes on the eye and the imagination. I am not just presenting a picture of Buttermeres pines, Snapes marshes, Beachy Head or Tintagel, I am there on location, experiencing and trying to articulate the beauty of these places. This awareness is what distinguishes a picture from a view, which to me is an ever-changing blend of geology and climate, seasons of the year, time of day, even my own mood at the time. It is the soothing dance of sun across a Dorset pasture, the flicker of light on the Thames, the tricks of rain clouds over a Yorkshire dale.

A view is a window on our relationship to the natural and man-made environment. The experience can be uplifting, some say spiritual. It prompted William Hazlitt to tell his readers always to walk alone (though afterwards to dine in company). To him other people were a distraction from the presence of nature, almost a sacrilege. Much of the greatest poetry and painting emanates from the solitary experience of landscape. Yet it is an experience that can also enrich our relations with each other. The art historian Kenneth Clark wrote, With the exception of love, there is nothing else by which people of all kinds are more united than by their pleasure in a good view.

The modern writer on landscape Robert Macfarlane likewise remarks, Every day, millions of people find themselves deepened and dignified by their encounters with particular places... brought to sudden states of awe by encounters... whose power to move us is beyond expression. I understand this concept of awe beyond expression, but in my view we must struggle to express it. If we do not, what we love will be taken from us. Awe needs champions. The landscape is a garden of delights but one as vulnerable as any garden. England is among the most intensely developed of the worlds leading countries. Yet it is a country whose landscape has for half a century been the most carefully protected against insensitive development. I regard that landscape as a treasure house no less in need of guardianship than the contents of the British Museum or the National Gallery. This book is a catalogue of its finest contents.

My approach is to list the best views in England. I accept that such a list is personal, and that there are hundreds of other equally glorious candidates. But I defend the concept of best, contesting the idea that beauty of any sort, especially of landscape, is subjective. The history of civilisation is of the search for a community of terms, for definitions of beauty that have general meaning, leading to discussion and conclusion. If visual beauty were purely subjective, conversation about art would cease and custodianship and conservation would have no basis. We must find agreement on what is lovely in our surroundings if we are to know what we are trying to protect. That agreement must start with a common terminology.

The language of landscape begins in geology. The rocks and earth of the British Isles, of which England comprises roughly a half, are more varied within narrower confines than of any country in Europe. The planets primal eruptions left England itself neatly divided by the long limestone spine of the Pennines and Cotswolds. To the west of this spine, volcanic rocks spewed up through sedimentary layers, mostly of old red sandstone, to produce the lumpy uplands of the West Country, the Welsh marches and the Lake District. The glaciation of subsequent ice ages eroded these mountains into the rounded hills and smooth-shaped combes we know today. To the east is a different geology, that of softer carboniferous limestone in the north and chalk and clay in the south. It yielded the gentler contours of the wolds and downs, the alluvial plains shaped by great rivers and the erosion of the coast by an invading sea.

England at the dawn of human settlement was mostly covered in woods. Pollen analysis shows post-glacial warming that pushed birch and pine northwards in favour of oak, elm, lime and ash. For all the claims of guidebooks, no truly wild woodland survives. The arriving Romans would have found an already managed landscape, cleared of much of its forest to meet the need for fuel, grazing animals and building materials. Englands last wild woodland is believed to have been the old Forest of Dean, and it was gone by the early Middle Ages.