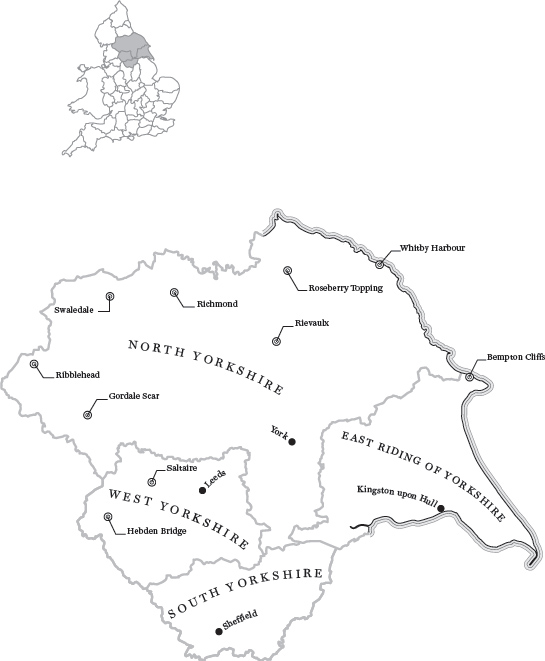

BEMPTON CLIFFS

Even the most ardent Yorkshireman would not claim the East Riding as blessed with Englands most beautiful coast. Despite patronage by David Hockney, the Yorkshire Wolds are a lost corner of England, a place of modestly rolling hills and sparsely populated valleys. The towns seem poor and the seaside resorts of Scarborough and Bridlington have seen better times. But where the wolds meet the sea they do so with a great roar of chalk.

The road from Hunmanby to Flamborough was, on my visit, deserted. Flamborough Head is cul-de-sac England, a place through which no one passes to anywhere else. It is Philip Larkins land, where removed lives are clarified by loneliness and silence stands like heat. A sign leads to the RSPB reserve of Bempton Cliffs, from where there is a short walk to the cliff edge, 130m above the sea.

East Riding chalk is less white than that of Englands south coast, being vividly layered in horizontal sheets, as if sediments of mud had mixed with the crustaceans on the sea floor. In places these layers are heaved and twisted, as at Lulworth in Dorset. Everywhere they are indented by erosion, creating deep gulleys, caves and passages, best appreciated from the sea (on the Yorkshire Belle out of Bridlington). This is a living, moving shoreline, with which the sea seems in perpetual combat.

The chief attraction of Bempton, indeed of much of Englands north-east coast, is ornithological. The RSPB has helpfully located decks at strategic points along the cliff edge, overlooking rocks and inlets with such names as Noon Nook, Scale Nap and Nettle Trip. They offer a clear view down to the sea and its caves. One cliff ends in a sculpted arch, except that the chalk is so angular as to look more like a woman in a skirt with one leg in the sea. Locals known as climmers used to descend these cliffs on ropes to collect much-prized guillemot eggs, dozens at a time, until banned in the 1950s.

Wild Bemptons great roar of chalk

Birds swarm over these cliffs in what is the busiest nature reserve in England, with 200,000 birds arriving each summer. They crowd the cliffs with their nests and fill the air with a curtain of shimmering white. Fulmars, guillemots, kittiwakes, razorbills and puffins are in a perpetual state of wheeling, calling and swooping over the waves.

Bempton claims to be the only mainland nesting sites for gannets, most athletic of seabirds and usually preferring rocks at sea. Fieldfares and redwings come down from Russia to winter on the shore. When I was there great excitement attended the arrival of a pair of short-eared owls. The bare fields above are alive with hares. Stoats and weasels reportedly inhabit the cliff tops.

The view south is towards Flamborough Head, scene of a confused and inconclusive battle during the American War of Independence in 1779. An American navy roaming the North Sea engaged a British convoy. The ships were French under French captains, but were commanded by an American, John Paul Jones, who was later idolised by Americans as a naval hero.

The view culminates short of Flamborough at North Cliff, roughly half the height of Bempton and thus creating the optical illusion of seeming further away. The lack of trees or any human settlement gives this coast a noble wildness. Humans seem intruders. It is a place for birds.

GORDALE SCAR

As the Pennine Way reaches the end of its Yorkshire stretch, it descends into the Malham valley. After a hundred miles of gritstone plateau, the change down to the softer limestone is abrupt, but the upland does not give up without a fight. At Malham Cove, a cliff of bare white rock looks out from a giant amphitheatre over the valley. Below is the picture village of Malham, from which a lane leads a mile to the east. A footpath then crosses a meadow and, so it seems, runs into the side of a cliff. A small notice offers not a map or explanation, but reproduces a painting in Tate Britain, James Wards Gordale Scar. This is tourist information with class.

Enveloping gloom: A View of Gordale by James Ward, c. 1812

Wards painting is often dismissed as a romantic exaggeration. I have to disagree. It seems accurate enough, and is confirmed by other paintings, notably by Turner. The scar is awesome, a narrow ravine 100m high, the apparent wreck of a glacial dry valley. Its floor is littered with debris, while through it flows the Gordale Beck, cascading from the plateau above and on to Malham and the River Aire, attractively lined with watercress.

As we progress into the gorge, the cliffs open and the shadows lengthen until the gloom is all-enveloping. The rock striations change from white to red to grey. Vast limestone shapes start out of the darkness. Round the final bend a waterfall appears in the depths of the scar, usually peppered with walkers trying to scramble up to the cliff top, a venture possible though difficult. Peregrines nest above.

Wards painting, with its blackened flanks and stormy clouds, was first exhibited in London in 1815 and made Gordale a celebrity venue. It surely inspired Wordsworths sonnet, Gordale, of 1818:

... let thy feet repair

To Gordale-chasm, terrific as the lair

Where the young lions couch; for so, by leave

Of the propitious hour, thou mayst perceive

The local Deity, with oozy hair

And mineral crown, beside his jagged urn

Recumbent.

I am sure there is oozy hair among the students and trippers who now crowd the spot, but the only deity is Gordale itself. This is nature at its most theatrical.

HEBDEN BRIDGE

From Fairfield

The Calder is one of Yorkshires neglected valleys. Like the Colne and the Aire it was ignored as scenic no-mans-land between the Peak and the Pennine national parks, considered insufficiently beautiful to merit protection. As a result planners and developers have visited a terrible fate on Calderdale.

That said, the dales capital of Halifax is distinguished, while Hebden Bridge, higher up the valley, is the most intact surviving Yorkshire mill town. Cloth was initially spun from local wool in farmhouses on the moor. In the 1850s, manufacture moved to the valley floor, where fast-flowing water powered ever larger mills. Hebden Bridge shifted from making cloth to making clothes, notably corduroy and fustian, supposedly strong enough to resist molten metal spilled from a forge. It was dubbed trouser town. A canal arrived, and later a railway.

With plentiful building stone, workers lived comparatively well, many in a distinctive type of hillside house known as a top and bottom, with legally unique flying freeholds. These were buildings of four storeys containing two homes, the bottom two floors accessed from the front below, the top two from the hill behind. Arranged in terraces, these houses dominate the appearance of the town, almost all built in the 1880s and 1890s. Prosperity lasted barely a century.