Simon Jenkins - The Celts: A Sceptical History

Here you can read online Simon Jenkins - The Celts: A Sceptical History full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Profile, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Celts: A Sceptical History

- Author:

- Publisher:Profile

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Celts: A Sceptical History: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Celts: A Sceptical History" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Celts: A Sceptical History — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Celts: A Sceptical History" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

v

For Dashiell and Nia

vi

- viii

This book is about groups of people and the words used to describe them. Such words are always controversial. My intention is to dispel the concept of a single Celtic people, language or nation. There are Ireland, Scotland and Wales, as well as Cornwall, Brittany and the Isle of Man. They have never in any respect cohered as one entity and I regard lumping them together as Celts or the fringe as distorting and dismissive.

However, since these peoples do share a language root and given that much of the book is about their joint relationship with England, I do refer to them as a group in the pre-historical period, using the term Celtic-speaking. Otherwise their languages are classified as Brythonic or Gaelic, and then Welsh, Irish, Gaelic or Breton. In other words, I try to call people and their language whatever they call themselves.

The words Britain and Britons are more confusing. They used to refer to all the British Isles, then to Celtic-speaking regions as distinct from the Germanic-speaking Anglo-Saxons, and then again to the island of Britain not Ireland. However, the word Britain is so often used as a convenience to refer to the whole of the British Isles, at least in early history, that this usage is hard to avoid. With the word Great it nowadays formally refers to England, Scotland and Wales but not Ireland. Only since 1801 has there been a so-called United Kingdom, first of Great Britain and Ireland and then, since 1922, of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. In the possible xiv event of Ireland reuniting, we must assume the UK will revert to GB.

This book is not an academic work but a history of an ongoing debate among scholars about the origins of the peoples of the British Isles and about their past, present and perhaps future relations. It does not carry notes, but works consulted and quoted are listed in the bibliography.

I have shown the text in whole or part to some of those closely involved in these debates, with whom I have conversed in the course of its preparation. They include Colin Renfrew, Barry Cunliffe, John Koch and Roy Foster. I thank them profusely, but they carry no responsibility for any mistakes I may have made, or for my conclusions. I have discussed devolution and independence over the years with too many to mention but have been helped in particular by Philip Stevens, Tom Jenkins, Tony Travers, my wife Hannah Kaye, and my assiduous editor Trevor Horwood. I would also thank my publisher Andrew Franklin and all at Profile Books.

The most vivid account of the geography of the British Isles appears in the first volume of the Oxford History of England, published in 1936. It refers to the islands as created in two parts. The western part is ancient, mountainous, rugged, broken, irregular, scrubby, sour-soiled and incommunicable in short, not a pretty place. The eastern part is a contrast, newer, softer, warmer, alluvial and fertile, attractive to invaders. The authors of the History assured readers that, despite this distinction, the series would be all-encompassing. It would narrate the story of the islands of Britain as a whole.

That promise was not kept, and is rarely kept in histories of the British Isles. Historians invariably direct their readers to the eastern half of the archipelago, the fertile, attractive side called England. This bias is reflected in the attention given to the peoples occupying the two sides, notably to the conflicts between them leading to the supremacy of the peoples of the east. Britons are taught from birth the story of England, just England. They are taught little or nothing of the others notably the Irish, Scottish and Welsh commonly referred to collectively as the Celts.

The first part of this book explains why the word Celt is a misnomer. As we shall see, scholarship since the 1960s has struggled to dismantle long-held theories of how the British people came into existence. This dismantling is important because, to a remarkable extent, theories of Celticism continue to fuel many of the prejudices and misconceptions that divide the peoples of the British Isles to this day. They both distort history and demean the distinctive characteristics of the Irish, Scottish and Welsh nations.

First among those misconceptions is that a people called the Celts invaded Britain from continental Europe sometime in the second or first millennium bc. There has never been found a distinct people, race or tribe claiming the name or language of Celtic. The word keltoi first appears in Greek as applied generally to aliens or barbarians, assumed to be inhabitants of western Europe before the rise of the classical world. In Latin, the term used is Galli or Gauls. Nowhere in this period was any such term applied to the people of the British Isles. Excavations in the nineteenth century of Iron Age sites at Hallstatt in Austria and La Tne in Switzerland were declared evidence of a Celtic civilisation, possibly even stretching from Asia Minor in the east to Portugal in the west. Its artefacts too were granted the designation Celtic, the style in use to this day.

As we shall see, early analysis of ancient DNA generally accepted that the peoples who occupied the British Isles dated back to a climatic migration northwards after the end of the last Ice Age. This migration occurred with global warming, primarily up the Atlantic coast of Europe from Iberia. On the eastern side of the islands, perhaps more recent DNA showed an occupation from continental northern Europe. There is little consensus on the balance between these two incursions, or when they occurred. Neither merits the title Celtic invasion.

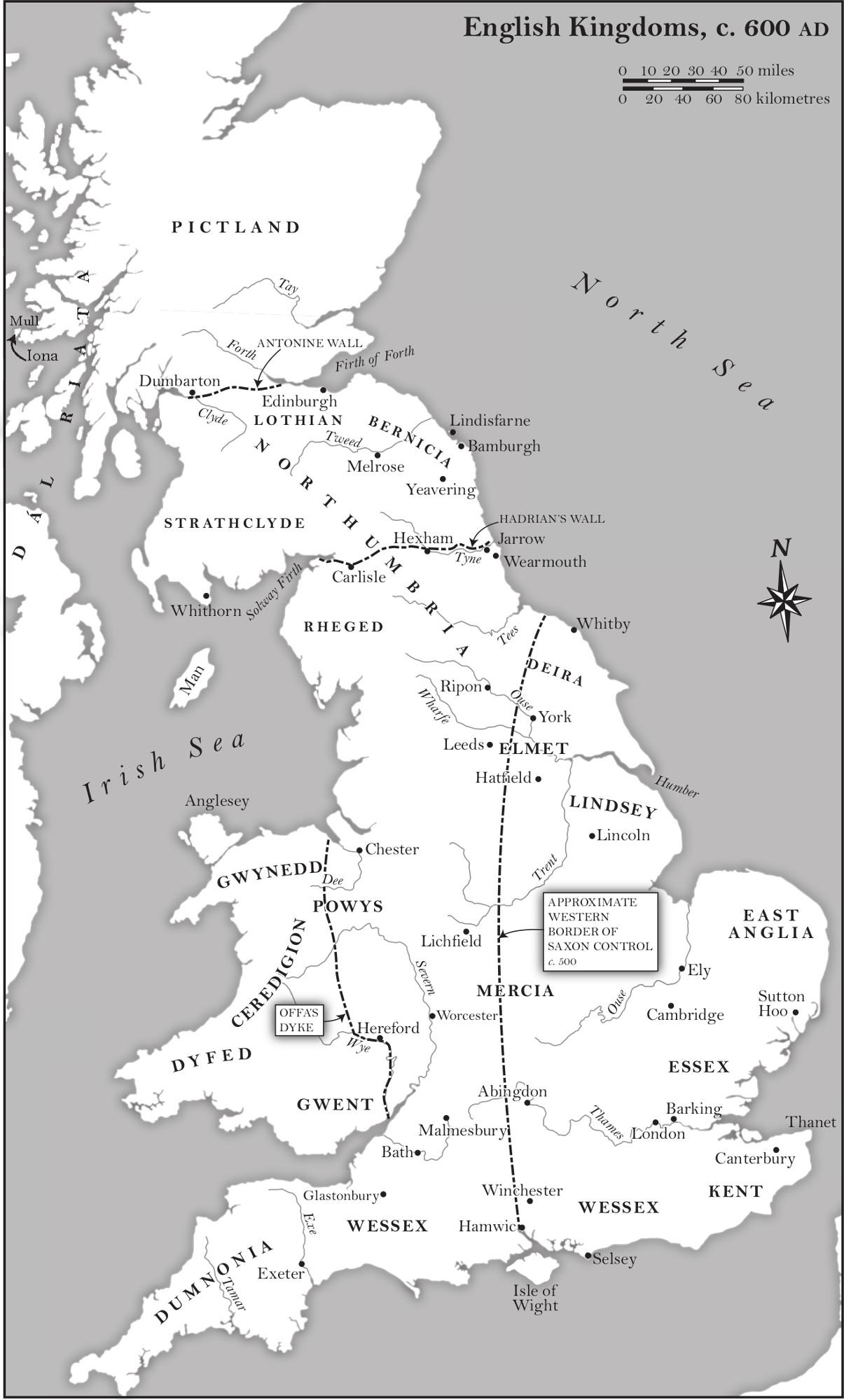

Probably in the late Bronze Age (c.2100800 bc ) these inhabitants of Britain came into contact with a variety of languages spreading across Europe that accompanied the growth of trade in metals. These tongues, loosely related to each other within the proto-Celtic Indo-European group, were assumed to have permeated every corner of the British Isles at least down to the period of the Roman occupation. That permeation is now doubted, with the eastern side of Britain thought possibly to have been speaking some version of the Germanic of northern Europe.

Certainly, two completely different language groups were in use in the British Isles by the second century after the withdrawal of the Roman empire. This was attributed to another misconception: a further mass incursion this time of Saxons in the fifth and sixth centuries, supposedly either wiping out the eastern Celtic speakers or driving them westwards across Britain. Like the Celtic invasion before it, this second one is also now discredited. While there are genetic signs of people migrating round the North Sea at the end of the Roman empire, there is nothing to indicate a wipe-out of its inhabitants and their total replacement throughout the length of eastern Britain. It is now thought possible that the many different peoples of the British Isles, east and west, evolved their own languages independent of any population movement. The east looked east and the west looked west.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Celts: A Sceptical History»

Look at similar books to The Celts: A Sceptical History. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Celts: A Sceptical History and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.