Copyright 2021 by Ivan Maisel

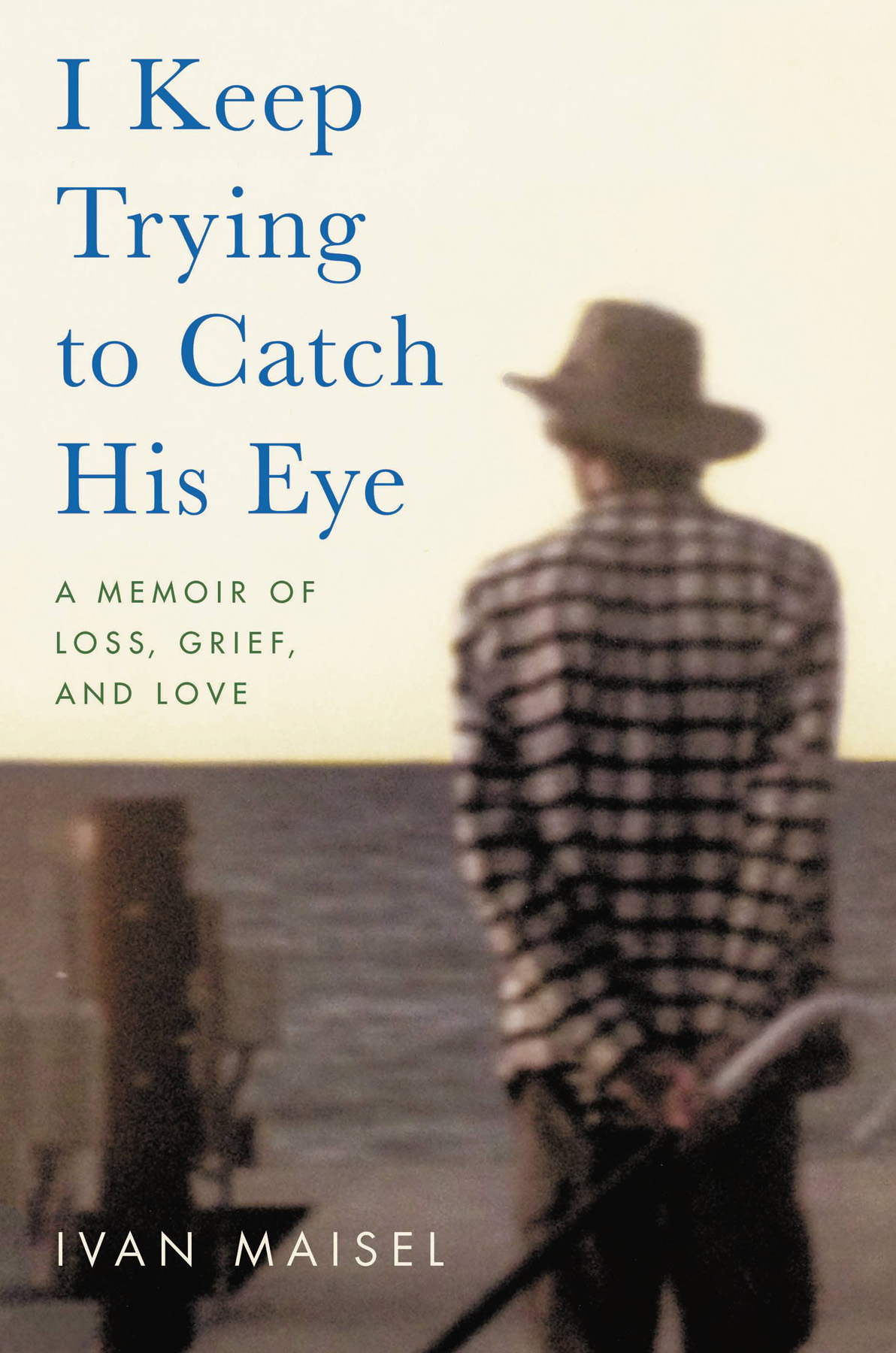

Cover design by Terri Sirma

Cover photograph Max Maisel

Cover copyright 2021 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

HachetteGo.com

Twitter.com/HachetteBooks

Instagram.com/HachetteBooks

First Edition: October 2021

Hachette Books is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Published by Hachette Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Hachette Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Maisel, Ivan, 1960- author.

Title: I keep trying to catch his eye : a memoir of loss, grief, and love / Ivan Maisel.

Description: First edition. | New York : Hachette Books, 2021.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021022739 | ISBN 9780306925740 (hardback) | ISBN 9780306925757 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Parental grief. | Teenagers--Suicidal behavior.

Classification: LCC BF575.G7 M34 2021 | DDC 155.9/37085--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021022739

ISBNs: 978-0-306-92574-0 (hardcover); 978-0-306-92575-7 (ebook)

E3-20210924-JV-NF-ORI

To Sarah

To Elizabeth

Lighthouses on my shore

A t 7:37 on a frigid Monday night in February, the house phone rang. It was 2015we still had a house phone. Meg had gone to a neighbors house to play mah-jongg. Elizabeth, our high school senior, had made her ritual retreat upstairs to her room. I had opened a can of Progresso Light Zesty Santa Fe Chicken Soup. I remember that detail. I walked around the kitchen island and answered the phone.

Is Margaret Murray there? a male voice asked.

This is her husband.

He identified himself as being from the sheriffs office in Monroe County, New York, which I knew to be the home of the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), where our middle child and only son, Max, was a junior.

Do you know a Max Maisel? he asked, pronouncing the last name MAY-zul, which is how the sitcom character on Amazon pronounces it, instead of May-ZELL, which is how my family has pronounced it since arriving from eastern Europe at the turn of the twentieth century.

Hes our son. How can I help you?

That is how you pick up the phone and find a trap door opening beneath you.

Maxs car had been sitting in the parking lot at Charlotte Park for twenty-four hours. Charlotte Park sits on the shore of Lake Ontario, north of Rochester, many miles away from our home in Fairfield, Connecticut. Megs brother Sean and his wife Deb own a vacation home a mile west of the park. Max has been coming to that home, to this park, every summer since kindergarten.

The sheriff called Meg because the car is registered in her name. He knew Maxs name because Border Patrol had a record of Max driving the car into Canada. Lake Ontario is within the Border Patrols jurisdiction because Canada is on the opposite shore.

Im reasonably sure the sheriff asked me the last time we spoke to Max. Im sure he asked a number of questions about Max. But I cant recount the conversation. My mind had already leaped past any logical explanation for his car being at the lake to the equally logical worst-case scenario.

Max was dead.

The sheriff told me he would call back in an hour. I took the soup off the stove, put it in a container, and shoved it into the refrigerator. I couldnt eat it. I never ate it. I stood there for five minutes, collecting my thoughts and rehearsing my phone call to Meg. I never seriously entertained thoughts of not telling her, giving her the last pain-free hour of her life, sitting in a neighbors den shuffling marble tiles around a tabletop.

I am a master of the art of conflict avoidance. I bob and weave, nod, sidestep, smile, hope for a way out. But when the conflict is directly in my path, I try to go straight at it. Lance the boil, we say in our house. Not to mention that if I gave Meg that extra hour, she would never forgive me.

I called her.

I need you to come home, I said, in as even a voice as I could muster.

Is everything OK?

I wasnt about to tell her over the phone that the light of her life was missing.

I need you to come home, I repeated.

On a very cold night of a very cold winter, our twenty-one-year-old son Max walked off an ice-slicked pier onto the surface of Lake Ontario. Wemy wife Meg, his sisters Sarah and Elizabeth, and Ipresume that he walked until the ice gave way beneath him. We dont know. We will never know.

An eyewitness saw him get out of his car, an eleven-year-old SUV that once had belonged to his beloved grandfather, and walk onto the pier.

Law enforcement eventually spotted some of Maxs belongings near the end of the pier, on the solid surface of the lake.

And eight weeks later, the fourth week of spring according to the calendar, Lake Ontario surrendered his body.

It would not be much of a whodunit. Those are the facts that we know. He left no note. Max wasnt much on communicating.

I Keep Trying to Catch His Eye is about the death of my son Max, the grief that engulfed our family, and how I learned to coexist with that grief.

I will not be so presumptuous as to include here how my wife and our two daughters have dealt with their grief. That consideration is pretty rich, given that what I do for a living as a journalist is become presumptuous enough to write a story and explain someone I hardly know. Butand this will not be the first time you read this in these pageslittle is more personal than grief.

All grief is personal, and all grief is as individual as the person doing the grieving. Love is personal, too, and there is certainly no shortage of writing about love. As I wrote, I began to understand that grief, if you get past the awkward social construct that American culture has with death, is the purest expression of love for someone who is no longer here to express it back. We mourn the deepest for those whom we love the most.

We view grief warily, as an alien force that invades us when we are at our most vulnerable. Im not going to pretend that I didnt suffer greatly when Max died. Im not going to tell you that I didnt ache, that I no longer feel a void. But as I learned how to go on with my life, as I wrestled with and tried to make sense of my pain, I began to see the direct correlation between the love I had for the son I lost and the depth of my painmy grief.

Grief is love.

For many years, I traveled on fall weekends with a small band of six to eight sportswriters who covered college football nationally. One of them, Chris Dufresne of the Los Angeles Times , married a woman I went to college with, Sheila Young. On those autumn trips, Chris brought with him an encyclopedic knowledge of the sport, a genial outlook, and a wicked sense of humor. He could be as funny in print as he was in person (the two dont always equate). We ate a lot of meals together, carpooled on the road to a lot of games.