Contents

Guide

ALSO BY DEAN HUGHES

FOUR-FOUR-TWO

MISSING IN ACTION

SEARCH AND DESTROY

SOLDIER BOYS

FOR MY GREAT-GRANDSON, BENJAMIN HSIUNG RUSSELL

An imprint of Simon & Schuster Childrens Publishing Division 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, New York 10020

THIS MOMENT DOES NOT DEFINE THEM [THE ESTIMATED SIXTY MILLION REFUGEES IN THE WORLD], BUT OUR RESPONSE WILL HELP DEFINE US.

PATRICK KEARON

1

Hadi Saleh was sitting on a stack of concrete blocks. He was leaning forward, looking down, the hood of his jacket pulled over his head. He could feel drops of rain pat against his shoulders and he could see the splashes on the wet sidewalk near his feet. The wheels of cars rolled slowly past him, sloshing out little currents of water against the curb. He crossed his arms against his chest to stay as warm as he could, and he waited. He knew, without thinking about it, how long it took until the light changed and the cars stopped, knew he had only a few more seconds to himself before he would have to face the drivers again. Still, he waited. A few drivers always ran the red light, and then the intermittent blast of car horns would turn into a full, wild blare.

It was always the same: honking, yelling, and frantic drivers maneuvering through the nightmare traffic, stopping only when they had no other choice. But finally the wheels did stop rolling, and Hadi got up. He walked around to the drivers side of the first car in line. He pulled cardboard packages of gum from his jacket pocketChiclets in four flavors: cinnamon, spearmint, fruit, and peppermint. He fanned out the boxes on his palms close to the window so the driver could see the choices. But the woman inside didnt look at him; she stared straight ahead. It was the usual thing.

So Hadi walked over to the first car in the inside lane, and he held the gum out again, this time on the passenger side. This driver, a young man, glanced at him, then shook his head. Hadi didnt say anything, didnt plead. He had tried that in the beginning, long ago, and found it was a waste of his time. He walked to the next car, and the next, back and forth between the two lanes.

An older man with a stubbly beard and tired eyes glanced toward him from one of the cars. His window was halfway open, even in the rain. He was smoking, holding his cigarette close to the window so the breeze drew the smoke up and out of the car. When Hadi stopped and presented his packages of gum, the man said without looking at Hadi, in a low, hostile voice, Why do you do this every day? No one wants your gum. Hadi turned to walk away, but he heard the man say, You Syrian pigs need to get out of our country. All of you.

Hadi didnt respond, didnt even give the mans words a second thought. He heard such things every day. Words didnt change what he had to do.

The clock in his head was telling him that the stoplight would soon turn green and the cars would start to move. Already, drivers who were nine and ten back from the intersection were beginning to honk. He had no idea why they thought that would speed things up. He made one last offer, got another headshake, then cut between two cars to the sidewalk and walked down the little slope to the corner, back to his stack of concrete blocks.

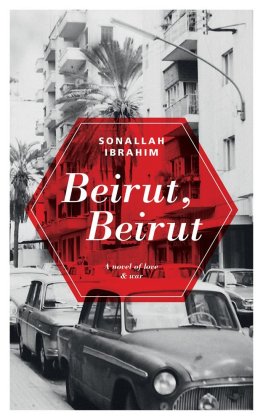

Hadi sat down and leaned forward. He listened to the patting of the rain on his hood again. At least the storm was light today. Rain came often to Beirut in the winter, sometimes falling in torrents. And even when it didnt rain, days were cold, sometimes windy. He was wearing a sweatshirt under his rain jacketone that had been given to him by a charity organization in his neighborhoodbut his feet were freezing, his hands, his face. Still, he was relieved there was no flooding at the bottom of the hill today. The splashes from the cars werent reaching him.

Before long he heard the slowing of tires, and the crazy honking started again. Hadi looked up, waited a few more seconds. There was a cabstand to the south, directly across the street. Cabbies sat there and smoked and talked. Most of them were Lebanese, not Syrians, and they liked to give Hadi a hard timemostly just teasing, but sometimes in filthy language. Hadi didnt like them very much, but one of them, a man named Rashid, let him store his chewing gum in a locked cabinet in the cabstand. Hadi got along all right with Rashid, but he tried to avoid the other men.

Hadi got up, started again. He walked to each car. The drivers stared away from him, or they shook their heads. This time no one cursed him or insulted him. But that didnt matter to Hadi. What mattered was that he sold no gum again.

Almost an hour went by before a woman, with her window already down, smiled and handed Hadi one thousand Lebanese poundsthe smallest bill the government printed. The woman chose the red boxcinnamonand she said in Arabic, Thank you, habibi. I hope youre not too cold.

The woman was pretty, and she was still smiling. She had called him my love.

Allah yehmik, he said. God protect you.

She nodded, and he thanked her. Chokran. He walked away, and he felt better. He finally had some moneya thousand pounds, or lira, as they were also called. He needed ten or twelve thousand to have a decent dayfifteen or twenty thousand for a great day. But it had taken a long time to get this first sale. Rainy days were bad. Car windows were mostly rolled up, traffic was congested, and people were unhappy, even more than usual.

But the woman had been nice to him. That was something.

The next hour was a little better. He received a five-hundred-pound coin from an older man who simply gave it to him without taking the gum, and a young man gave him two one-thousand-pound bills. Not often did anyone give him so much. But another man hissed at him, I can smell you from here. You should stay in the sewer, where you belong.

The rain let up after a time, but Hadi still looked at the sidewalk, not at the cars, and he listened for them to stop. Maybe, with the sun peeking out, people would be happier. Maybe more of them would buy from him. But there was no telling. Some days were better than others. Inshallah, his father always said. God willing. But his father was never happy when Hadi came to him at the end of a day with only five or six thousand poundsGod willing or not. That much would buy a package of flat bread and a little rice, but it would leave nothing for other expenses. Hadi and his father had to earn enough each day to buy food for nine in the Saleh family, but they also had to save each day to pay for rent and electricity. The rent for their single room, for a month, was 240,000 Lebanese pounds, and there was nothing cheaper anywhere in Beirut.

Hadi wished that he could sleep for a little while. His brain felt numbdulled by the daily buzz of tires on pavement, deadened to the curses he heard. Every day he saw Lebanese children walking by on their way to school. They laughed and made jokes with each other. He sometimes wondered what that would be like, to sit in schoolnot out in the rainand read books, learn things. But it didnt help to wonder; he was better off letting his mind drift, not thinking too much.

But then he spotted a car he knew. It was the couple he called the foreigners because they didnt speak much Arabic. They always gave him money, and they didnt take any gum. So he stood, waited, and when the light changed, walked directly to their car. It was what he needed today: to hear them greet him with the clumsy Arabic they knew and to see their happiness. Today they handed him not only a thousand pounds but a shawarma sandwich. They gave him something to eat fairly often, once a week or so.