Copyright 2017 by Alia Malek

Published by Nation Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

116 East 16th Street, 8th Floor

New York, NY 10003

Nation Books is a co-publishing venture of the Nation Institute and Perseus Books.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Perseus Books, 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104.

Books published by Nation Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at Perseus Books, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special.markets@perseusbooks.com.

Designed by Linda Mark

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Malek, Alia, 1974author.

Title: The home that was our country : a memoir of Syria / Alia Malek.

Description: New York, NY : Nation Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc., 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016037114 (print) | LCCN 2016050029 (ebook) | ISBN 9781568585321 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781568585338 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Malek, Alia, 1974Family. | Damascus (Syria)Biography. | Damascus (Syria)History. | SyriaHistory.

Classification: LCC DS99.D3 M346 2017 (print) | LCC DS99.D3 (ebook) | DDC 956.91/440423092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016037114

E3-20170203-JV-PC

For my parents,

for Maha,

for Teta

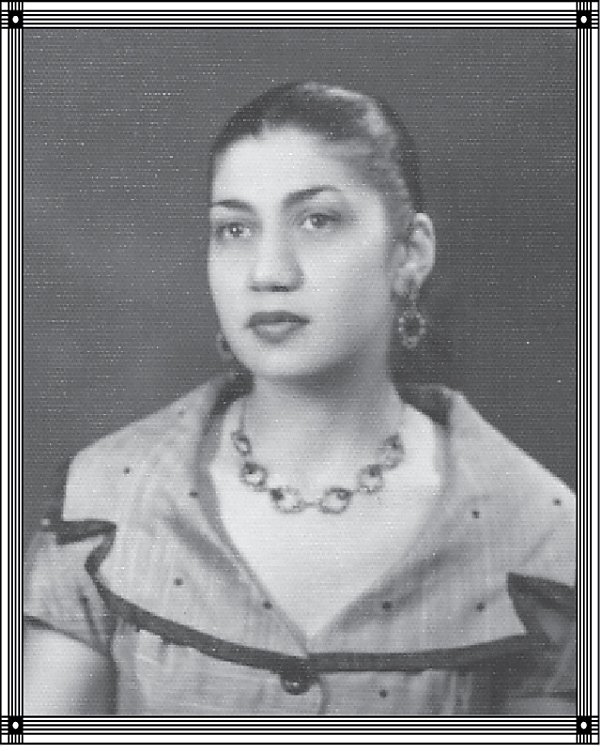

Authors grandmother, ca. 1955

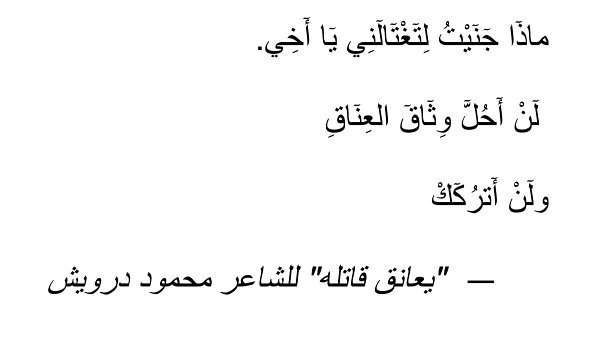

What crime did I commit for you to annihilate me, my brother?

I will never release the binds of this embrace.

And I will never let you go.

He Embraces His Murderer, Mahmoud Darwish

T HE CHALLENGE OF TRANSLITERATING FROM A RABIC INTO E NGLISH is that there are many systems used by authors and scholars to represent the Arabic sounds and short/long vowels that can only be approximated in the Roman alphabet. Strict adherence to this or any other system of transliteration, however, can often obfuscate a word or concept readers may already have come across, especially with Syrian towns and names constantly appearing in the news over the course of the current conflict.

Many readers may be unaware that there are various spoken dialects of Arabic that differ from Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). Thus my goal was to stay as true as possible to both Syrian dialect when spoken and to correct MSA when called forwithout compromising readability for non-Arabic-speaking readers. For that reason, I have made a few choices. First, I have opted not to use most diacritics, which might end up confusing more readers than they would help, but I did represent the back-of-the-throat  as a () and the

as a () and the  , or glottal stop, as (). And second, where there are Arabic words, proper nouns, or English approximations of Arabic concepts that readers will likely recognizefor example Tahrir, Alawite, Shiite, AinIve opted to use them.

, or glottal stop, as (). And second, where there are Arabic words, proper nouns, or English approximations of Arabic concepts that readers will likely recognizefor example Tahrir, Alawite, Shiite, AinIve opted to use them.

A Note on Names

Almost all names have been changed in this book to safeguard as much as possible peoples privacy and safetythis includes both given and family names. Pseudonyms are consistent with era, language, and meaning of original name. Should a real Abdeljawwad al-Mir exist anywhere, it is purely by coincidence.

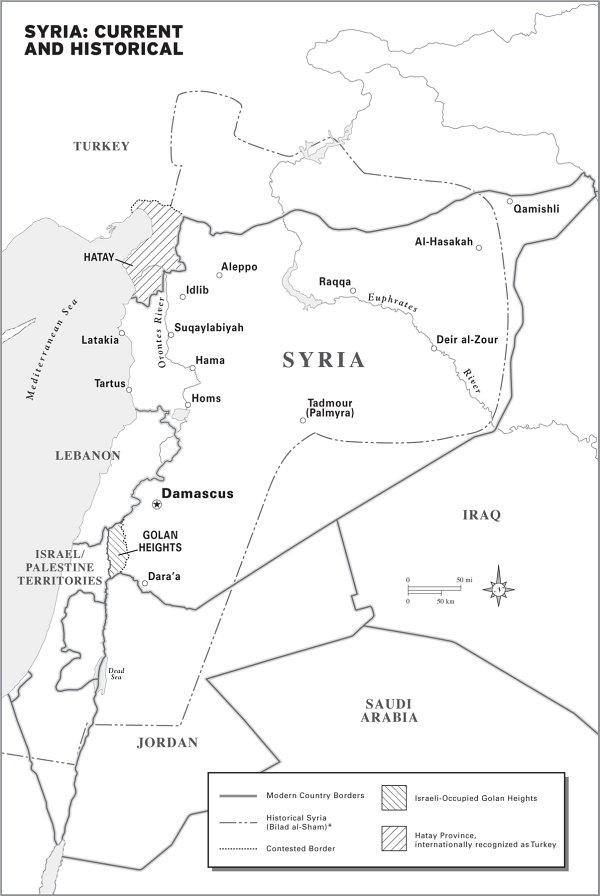

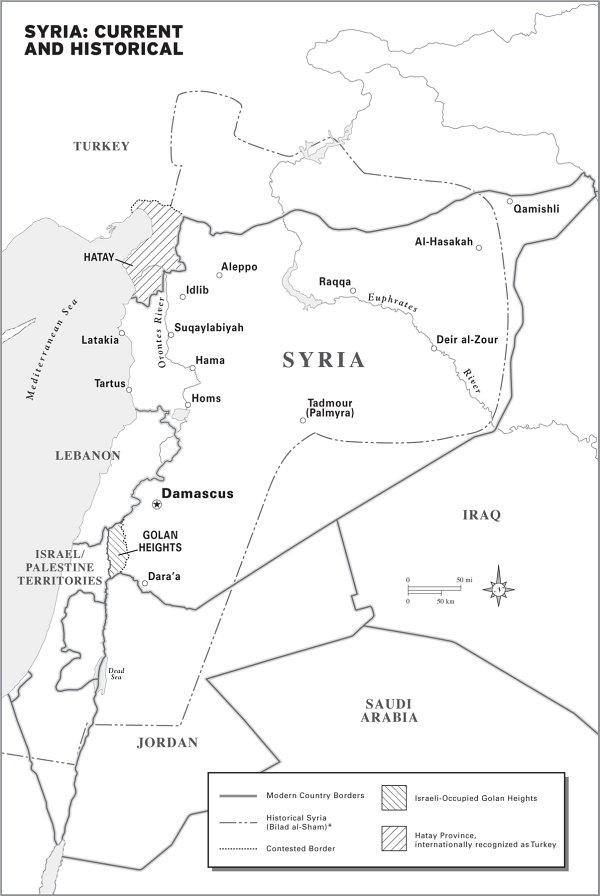

*Bilad al-Sham does not refer to a fixed geographic entity with sharp border distinctions as shown on the map. This rendering is merely to assist the reader visualize what is elucidated in the text.

Damascus, May 2013

B Y THE TIME I LEFT S YRIA IN M AY 2013, MANY IN MY FAMILY WERE happy to see me go.

For them, the day hadnt come soon enough.

The country was already more than two years into the blackness that would consume it. Its disintegration would see hundreds of thousands killed; millions displaced from their homes both inside and outside Syrias borders; villages, towns, and cities in rubble; unknown numbers disappeared; and the futures of several generations stolen.

When authoritarian regimes in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya were overthrown in 2011, all eyes turned to Syria as if it would be next. But despite both peaceful and armed opposition, the regime that had ruled Syria for over forty years remained entrenched. Syrian president Bashar al-Assadwho had inherited power from his father, Hafez al-Assadblamed a foreign conspiracy at work against Syria. The regime dismissed any reports that would belie its account of events as fabrications, venomously accusing the media of perpetuating lies. Western journalists had already disappeared and died in Syria to much international attention. Syrian journalistsprofessionals and those initiated in citizen reportingwere dying as well, just more silently and in greater numbers.

So as far as many in my family were concerned, my being both a dual national American and a journalist added up to nothing but trouble, and the sooner I left, the better.

While most foreign journalists were denied legal access to Syria, I had been able to enter and move about Damascus with relative ease. Though I was born abroad, both my parents are Syrian, and, more importantly, had registered my birth with the government, in anticipation of our planned return to Syria, where they had intended to raise their family. That meant that I had a Syrian national identity card and the access it can provide.

Ever since moving to Damascus in April 2011, I had been constantly answering inquiries as to what I was doing there. Although people regularly pry in Syriamost often about your relatives, your marital status or prospects, or your income and propertythe question as to why I was in Damascus now was more than mere prosaic meddling. It was potentially dangerous.

Unlike in many other cities, there is no anonymity in Damascus. There is no disappearing into it. Four different security bodies, known collectively as the mukhabarat, with at least twenty-two branches in the capital alone, have for decades carried out the regimes surveillance of its people. (It is estimated that the mukhabarat have 65,000 full-time employeesor 1 for every 153 adult citizensalong with hundreds of thousands of part-time or unofficial employees.) They are a much less refined version of the Stasi, with very little of the East German agencys precision or accuracy. What they lack in sophistication, though, they more than make up for with gusto.

The best way to explain this is with a joke I first heard back in Syria in the 1990s. It goes like this: the worlds intelligence services gather at an elite training site. Present are the CIA, the KGB, Israels Mossad, and the Syrian mukhabarat. They are brought to the edge of the forest and told they must each go in, track a certain fox, and bring him back. Both the CIA and the KGB get it done in an hour. The Mossad completes the task even faster. The last to go are the Syrian

as a () and the

as a () and the  , or glottal stop, as (). And second, where there are Arabic words, proper nouns, or English approximations of Arabic concepts that readers will likely recognizefor example Tahrir, Alawite, Shiite, AinIve opted to use them.

, or glottal stop, as (). And second, where there are Arabic words, proper nouns, or English approximations of Arabic concepts that readers will likely recognizefor example Tahrir, Alawite, Shiite, AinIve opted to use them.