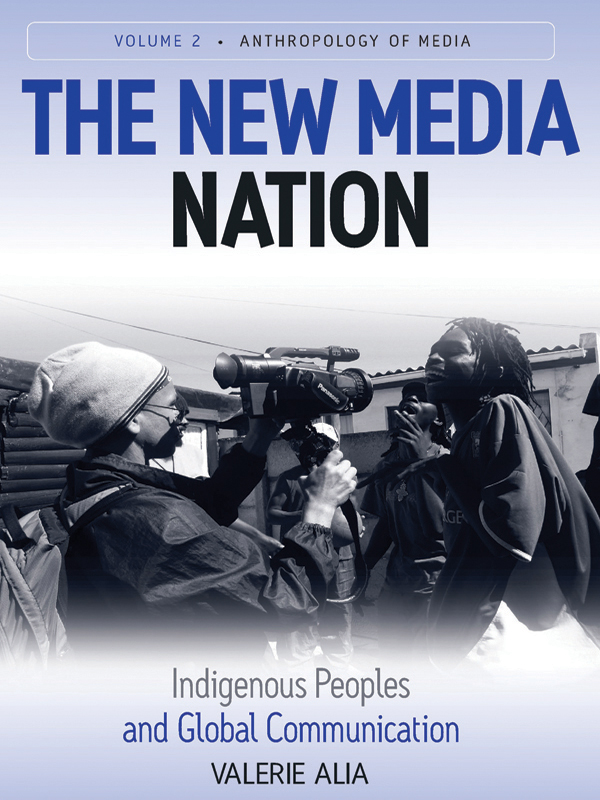

Anthropology of Media

Series Editors: John Postill and Mark Peterson

The ubiquity of media across the globe has led to an explosion of interest in the ways people around the world use media as part of their everyday lives. This series addresses the need for works that describe and theorize multiple, emerging, and sometimes interconnected, media practices in the contemporary world. Interdisciplinary and inclusive, this series offers a forum for ethnographic methodologies, descriptions of non-Western media practices, explorations of transnational connectivity, and studies that link culture and practices across fields of media production and consumption.

Volume 1

Alarming Reports: Communicating Conflict in the Daily News Andrew Arno

Volume 2

The New Media Nation: Indigenous Peoples and Global Communication

Valerie Alia

Volume 3

News As Culture: Journalistic Practices and the Remaking of Indian Leadership Traditions

Ursula Rao

Volume 4

Theorising Media and Practice

Edited by Birgit Bruchler and John Postill

Volume 5

Localizing the Internet: An Anthropological Account

John Postill

First published in 2010 by

Berghahn Books

www.berghahnbooks.com

2010, 2012 Valerie Alia

First paperback edition published in 2012

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Alia, Valerie, 1942

The new media nation : Indigenous peoples and global communication / Valerie Alia.

p. cm. (Anthropology of the media)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-84545-420-3 (hbk) ISBN 978-0-85745-606-9 (pbk.)

1. Indigenous peoplesCommunication. 2. Indigenous peoples and mass media. 3. Internet and indigenous peoples. 4. Telecommunication. 5. Communication and culture. I. Title.

GN380.A45 2009

302.23089'97dc22

2009025363

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Printed in the United States on acid-free paper.

ISBN: 978-0-85745-606-9 (paperback) ISBN: 978-0-85745-409-6 (ebook)

Preface

This is the moment freedom begins-the moment you realize someone else has been writing your story and it's time you took the pen from his hand and started writing it yourself. The greatest challenge to themedia giants is the innovation and expression made possible by the digital revolution. I may still prefer the newspaper for its investigative journalism and in-depth analysis, but we now have . the means to tell a different story than big media tells.. This is the real gift of the digital revolution. The Internet, cell phones and digital cameras that can transmit images over the Internet, make possible a nation of story tellersit's not a top-down story anymore. Other folks are going to write the story from the ground up.

Bill Moyers, US broadcaster and journalist

Native people are doing for themselves what cannot be accomplished by the mainstream media. They are sharing their communities' concerns in their own voices, uninterrupted by cultural interpreters and reporters who lack the background to understand the complex issues of contemporary Native life.

Peggy Berryhill, Native American broadcast producer

To me one of the answers comes through Native people creating books, films and radio stations. I believe control of our own institutions is going to empower us; being able to get the story, tell our story, work and edit our stories . For the first time Native people are on the breaking edge of information technology in terms of computer systems and the internet, which means that we're going back to an old tradition, the oral visual presentation and the storyteller's credibility.

Paul DeMain, Oneida/Ojibway journalist

Thus, Paul DeMain brings things full circle. Old traditions flow into new technologies; change is organic, not anomalous. DeMain is a leading Indigenous journalist of Oneida/Ojibway ancestry, a publications editor, radio presenter, and media activist who pointedly titles the piece from which that paragraph is quoted, Guerillas in the Media. Guerillas, indeed. Like other Indigenous media leaders around the globe, DeMain is at once a guerilla and a legitimate journalistnot eitheror, but both. That is a theme to which we will return throughout this exploration of The New Media Nation. In 2004, reflecting on the end of the United Nations Decade of Indigenous Peoples, I wrote:

The world's Indigenous peoples have experienced both progress and frustration in the past decade. Important developments include a comprehensive Arctic Policy brought in by the ICCInuit Circumpolar Council (formerly Inuit Circumpolar Conference)one of the first NGOs to gain UN recognition; signing of the Nunavut Agreement between Inuit and the Government of Canada and founding in 1999 of Nunavut Territory, whose 85% Inuit majority has helped to spark a cultural revival across the circumpolar world. It was preceded by Greenland's acquisition of home rule from Denmark. Siberian peoples are culturally thrivingand dying from economic, environmental and social conditions. Residential/missionary school abuse is variously addressed and ignored in Canada, Australia, the United States and other countries.

The ICC's Arctic policy could not be timelier in the face of global warming, arguments over Kyoto and proposed industrialization of fragile lands and waters. Amazonian peoples and their environments remain threatened. On the proactive side, the Fair Trade movement is attempting to address environmental, social and economic problems on a global scale, and in the Nordic countries Smi cultural, social, political and communications advances join the world-wide movement of Indigenous-run media networks that I have called The New Media Nation. I think it heralds the rise of a new media universe. Until recently, representations of Indigenous peoples were primarily by outsiders and Indigenous people were excluded from positions of influence in media industries.They were portrayed as exotic items for study or observation, in need of civilizing. Womenin the vanguard of many movements, including the Mori Renaissance and what might be called the Inuit cultural and political renaissancewere marginalized or trivialized (Alia 2004b).

Previous publications have illuminated particular facets of the Indigenous media picture. These include the pivotal studies of broadcasting in Canada by Lorna Roth and Gail Valaskakis (Roth 2006, 2000, 1996, 1995, 1993; Roth and Valaskakis 1989); Michael Meadows' and Helen Molnar's work on Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander media (Meadows 2001; Meadows and Molnar 2002; Molnar and Meadows 2001); Ritva Levo-Henriksson's (2007) study of Hopi radio; Ann Fienup-Riordan's (1995) study of Alaska Eskimos in film; the autobiographical writings of Inuit photographer/writer/artist Peter Pitseolak (Pitseolak 1997; Pitseolak and Eber 1975, 1993); the historically and politically grounded studies of Smi media by Veli-Pekka Lehtola (2002, 2005) and Sari Pietikinen (2003); Michael Keith's (1995) work on Native American broadcasting; work by Patrick Daley and Beverly James (2004) on Alaska Native media; Donald R. Browne's (1996) study of electronic media; Neil Blair Christensen's (2003) study of Internet use in Greenland; collections on Indigenous literature in North America (Swann 2004; Harjo and Bird 1997; Petrone 1992, 1990, 1988); international collections focused mainly on film and video, (Stewart and Wilson 2008; Ginsburg, Abu-Lughad, and Larkin 2002) and on Africa (Wasserman and Jacobs 2003); collected essays on Aotearoa/New Zealand (Dennis and Bieringa 1996); my earlier Canada-based work (Alia 1999) and first look at the international perspective, in the essay, Scattered Voices, Global Vision: Indigenous Peoples and the New Media Nation (Alia 2003).