First published 1997 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon 0X14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1997 Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 97-8950

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jenness, Valerie, 1963-

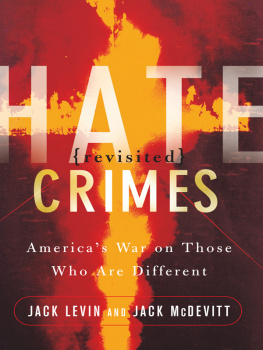

Hate crimes : new social movements and the politics of violence / Valerie Jenness and Kendal Broad.

p. cm. (Social problems and social issues)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-202-30601-1 (cloth : alk. paper); 0-202-30602-X (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Hate crimesUnited States. 2. Social movementsUnited States.

3. GaysCrimes againstUnited States. 4. WomenCrimes againstUnited States. I. Broad, Kendal. II. Title. III. Series.

HV6250.3.U5J45 1997 97-8950

364.1dc21 CIP

ISBN-13: 978-0-2023-0602-5 (pbk)

To those who make others safe(r) by

working against violence born of bigotry.

May they be successful.

And, to L.M.G. (aka little Lisa),

who, at age two, knows nothing about

the politics of violence and victimization.

May she always be safe.

Contents

We would like to acknowledge the many activists and policymakers who provided us with information about themselves, their work, and their organizations. We are especially thankful for assistance from the National Institute Against Prejudice and Violence, the Center for Democratic Renewal, the Southern Poverty Law Institute, the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, and the Anti-Defamation League of Bnai Brith. Without organizations like these, and the people who sustain them, our research would have been impossible. In addition, we gratefully acknowledge the cooperation of the publishers who allowed select portions of previously published work to be reprinted as part of this book. Specifically, we thank the publishers of Gender & Society (Sage); Social Problems (University of California Press); Images and Issues: Typifying Contemporary Social Problems (1995), edited by Joel Best (Aldine de Gruyter); and Research on Social Movements, Conflicts and Change (JAI).

We would also like to thank the many colleagues who read all or parts of this work and offered helpful comments, including: Naomi Abrahams, Barry Adam, Joel Best, Ryken Grattet, Shirley Jackson, Armand Mauss, Lisa McIntyre, Eugene Rosa, Beth Schneider, Carole Sheffield, and Verta Taylor. In addition, the diligent library research of Leslie Atkins, Colette Casavant, Theodore Curry, Jane Florence, Glenn Manry, Aaron McCright, Jeannine Moga, and Kari Norgaard contributed to the contents of this book, and the technical assistance of Patty Meyer contributed to its form.

In the final stages of putting this book together Arlene Perazzini at Aldine made publication of this book possible by covering for us when the unpredictability of life interfered with the completion of this book on time. Also during the final stages of completing this book, Naomi Abrahams, Bill Bielby, bobbi bonace, Debbie Curran, Jack Dugan, Shoshanah Feher, Sarah Fenstermaker, Ednie Garrison, Melanie and Alan Gay, Ryken Grattet, David Greenberg, Jo Hockenhull, Shirley Jackson, Nancy Jurik, Cheryl Lepper, Averell Manes, Armand Mauss, Lisa McIntyre, Jennifer Pierce, Tim Reed, Gene Rosa, Beth Schneider, Jim Short, Geoff Sternlieb, Judy Stone, Nol Sturgeon, Verta Taylor, Charles Tittle, Peter Williams, and especially Mike and Lassie Bonner ensured that the least desirable elements of real life did not have their way and preclude the completion of this book. They, individually and collectively, deserve thanks beyond that which words can convey, but is nonetheless understood.

I

A New View of Hate-Motivated Violence

Introduction

Physical violence born of bigotry takes many forms. Consider just four events: First, in Raleigh, North Carolina, two white men beat to death a twenty-four-year-old Chinese-American man, Jim Loo, with the butt of a gun and a broken bottle. Afterward, the men explained that they attacked Mr. Loo because they did not like orientals (Fernandez 1991). Second, just after midnight on the most sacred Sabbath of the Jewish new year, two teenagers desecrated a synagogue in Brooklyn, New York. The boys spray-painted swastikas on the walls, set fires around the building, and ripped up and burned six Torah scrolls. Jewish tradition considers such desecration equivalent to murder (ibid.). Third, in Concord, California, a local AIDS activist received repeated telephone threats, including a bomb threat, at his home and at the store where he worked. One caller told the activist, We dont want any faggots in Concord and that he should leave town If you care about your friends. In order to protect his friends and fellow employees, the activist left his job and moved to another community (National Gay and Lesbian Task Force 1991). Fourth, two young women were playing tennis on a university campus in Nebraska when three men attacked them and used the womens clothing to tie them up. Both women were then raped. The women reported that their attackers later bragged to them that they had been stalking them and had similarly attacked other women (Majority Staff of the Senate Judiciary Committee 1992:iii). The examples are endless, but the point remains: activities such as these, as well as many others, have long existed and are increasingly defined as hate crime in the United States.

Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s, hate crimes emerged to secure a place in the social problems marketplace (Best 1990; Hilgartner and Bosk 1988). In his 1990 State of the Union Message, President Bush (1990) acknowledged and addressed the problem when he said, Every one of us must confront and condemn racism. Anti-Semitism. Bigotry and hate. Not next week, not tomorrow, but right now. This declaration was later underscored by John Conyers, Jr., member of the U.S. House of Representatives, who argued, [W]hether based on sexual orientation, race, religion, or ethnicity, bigotry and the violence it inspires poses a grave threat to the peace and harmony of our communities. The need to alert Americans to this threat is great (Conyers 1992:xv). Proclamations such as these illustrate the way in which select instances of bias-motivated violence have been recognized as hate crime and as evidence of a growing social problem.

Over the last decade and a half, hate crimes in particular and hate-motivated violence more generally have become the subject of highly politicized public debates, mandates that something must be done, and proposals for both legal reform (Bensinger 1992; Grattet, Jenness, and Curry 1997; Jenness and Grattet 1996; Levin 1994; Levin and McDevitt 1993) and extralegal reform (Bensinger 1992; Broad and Jenness 1996; Center for Democratic Renewal 1992; Jenness and Broad 1994; Jenness 1995a, 1995b, 1996; Levin and McDevitt 1993). Increased public discussion of hate crimes has taken many forms, including editorials in many of the nations most prestigious papers, official hearings before both houses of Congress, and an increasing number of publications attesting to the urgency and scope of the problem of hate-motivated violence in the United States. Journalists, activists, politicians, educators, law enforcement officials, and more recently social scientists have written volumes on the causes, manifestations, consequences, and control of hate crimes. Combined, these activities have ensured that select types of conductbias-motivated violencehave become identifiable as a social problem. In the process, heretofore private injuries of select groups of individuals have been transformed into a public issue, and select constituenciespeople of color, Jews, immigrants, gays and lesbians, women, those with disabilities, etc.increasingly have been recognized as real and potential victims of violent criminal conduct. But how have these institutional changes occurred?