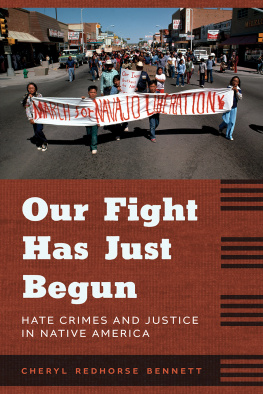

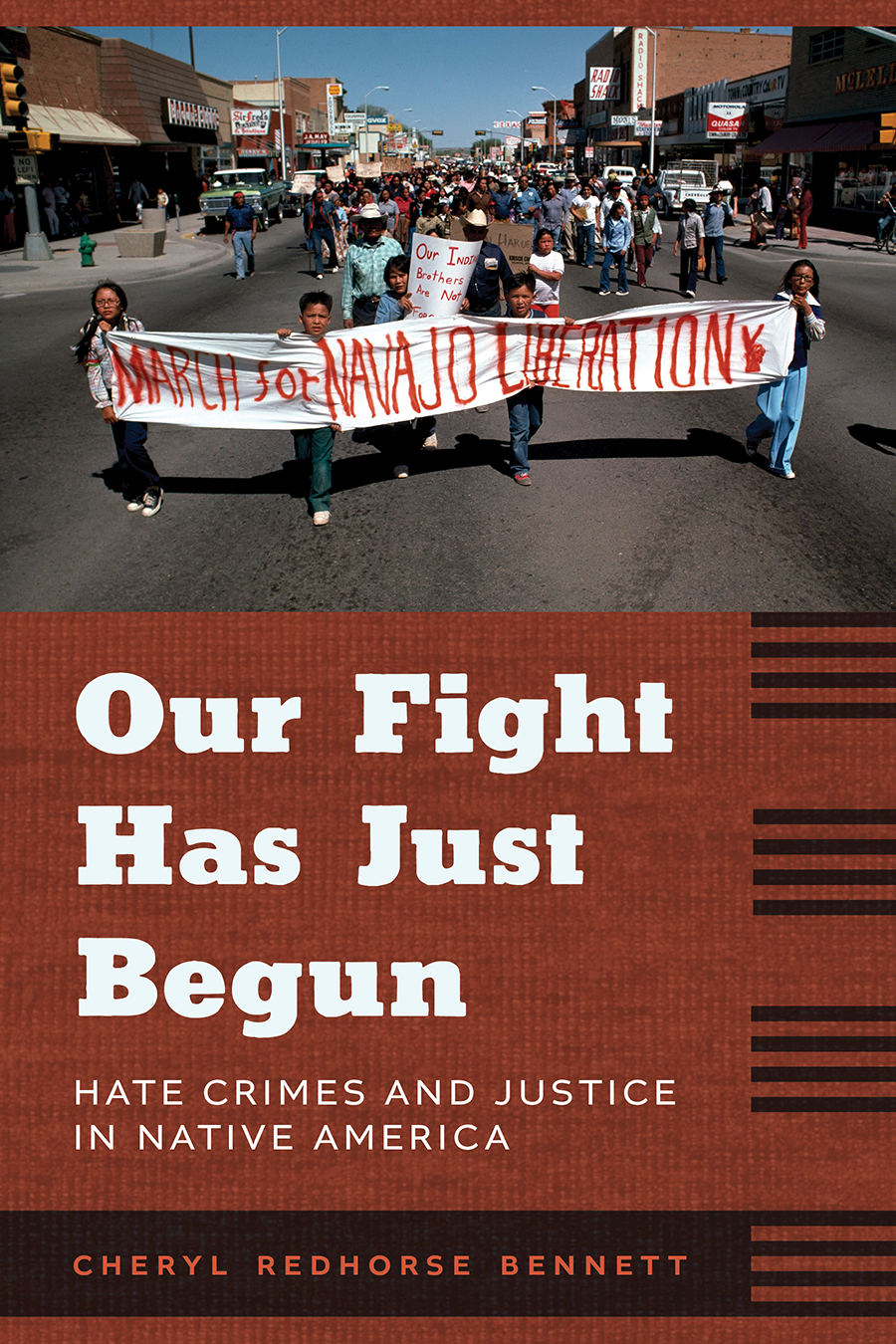

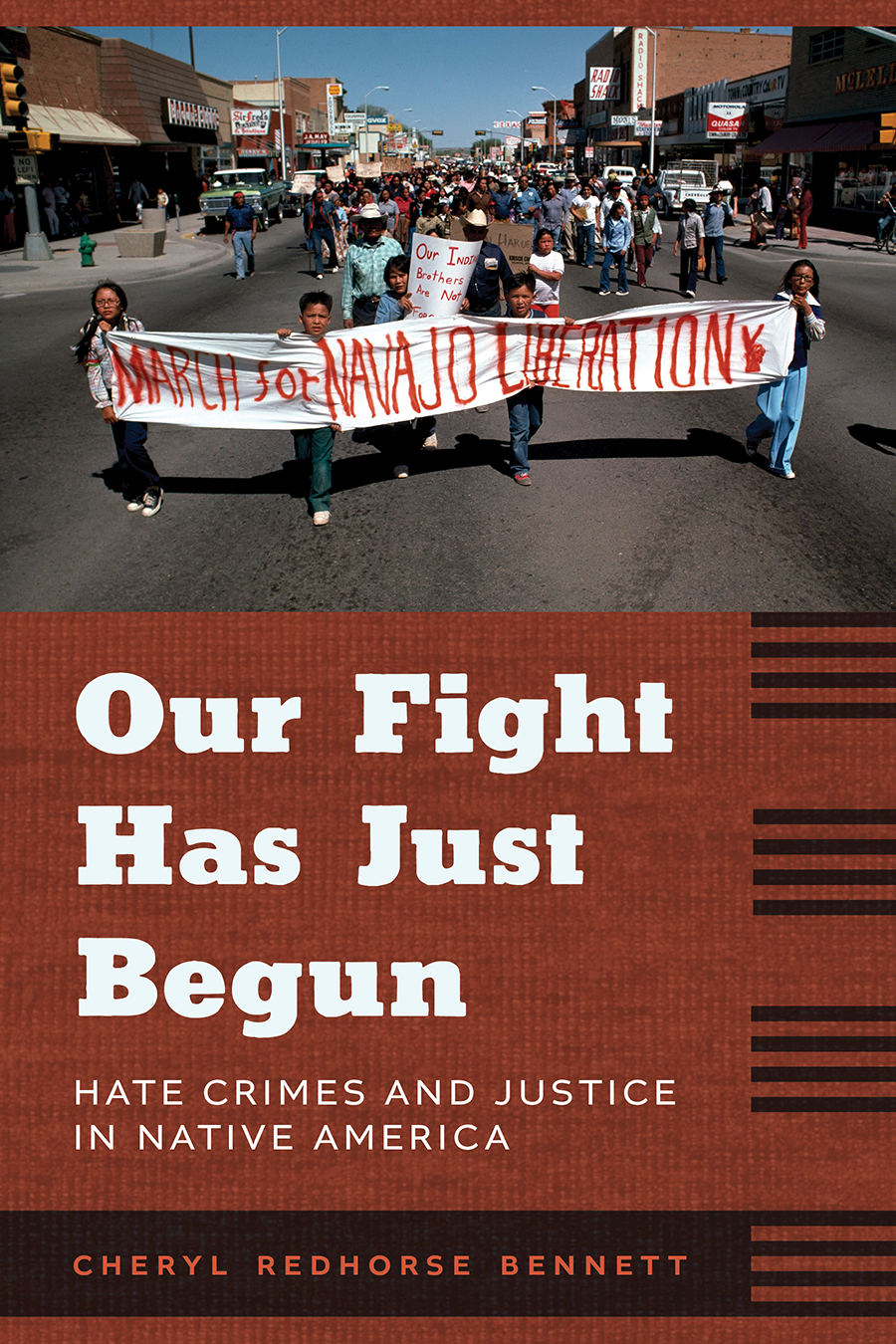

Our Fight Has Just Begun

Our Fight Has Just Begun

Hate Crimes and Justice in Native America

Cheryl Redhorse Bennett

The University of Arizona Press

www.uapress.arizona.edu

2022 by The Arizona Board of Regents

All rights reserved. Published 2022

ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-4168-3 (hardcover)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-4167-6 (paperback)

Cover design by Leigh McDonald

Cover photo: Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Typeset by Sara Thaxton in 10.25/15 Minion Pro with Cutright WF, Altivo, and Helvetica Neue LT Std

Publication of this book is made possible in part by the proceeds of a permanent endowment created with the assistance of a Challenge Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, a federal agency.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bennett, Cheryl Redhorse, 1978 author.

Title: Our fight has just begun : hate crimes and justice in Native America / Cheryl Redhorse Bennett.

Description: Tucson : University of Arizona Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021038742 | ISBN 9780816541683 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780816541676 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Navajo IndiansCrimes againstFour Corners Region. | Hate crimesFour Corners Region. | RacismFour Corners Region. | Four Corners RegionRace relations.

Classification: LCC E99.N3 B46 2022 | DDC 305.8009792/59dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021038742

Printed in the United States of America

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This book is dedicated to the Native American victims and survivors of hate crime.

Contents

Preface

The fight has only begun and we are prepared spiritually with human dignity, to carry on our fight in all avenues that we consider necessary in order to be heardnot as militants or as fanatics, but as human beings, as Navajos.

Larry Emerson for the Coalition for Navajo Liberation, Navajo Times, 1974

A s a Din and Numunuu woman from Din Bikayah (Navajo land) I am no stranger to race, racism, and hate crime. I experience racism daily as a citizen of the Navajo Nation, and I also experience discrimination daily as a woman of color. Growing up, I often thought I was overanalyzing racism and discrimination. Yet some of my experiences reveal how racism is embedded into the fabric of our culture. This book is about race, racism, and bias-motivated hate crimes committed against Native Americans in the Four Corners.

I grew up in the small community of Kirtland, New Mexico, near the reservation border town of Farmington. The San Juan River, which lies south of Kirtland, is the only physical boundary separating Kirtland from the Navajo Nation. Farmington is part of the Four Corners region, where the four states of New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah meet. The town lies within a valley, and sharp jutting mesas and vast desert wilderness surround the town, where three rivers meet. Navajo people, or Din, call Farmington Totah, which translates as three waters. Farmington is a blue-collar town, with a predominantly white population among Native American and Hispanic peoples. Farmington, nestled within the Republican stronghold of San Juan County, is a conservative hub in the otherwise Democratic state of New Mexico. The Navajo Nation is close to Farmington: at the southern edge of the town, just across the San Juan River, is the Navajo Nations northern border. Farmingtons place just eighteen miles west of the Navajo Nations western border locates it nearly within the Navajo Nation and qualifies it as a reservation border town. When whites settled the area after 1866, the river became the boundary between traditional Navajo farms and new white settlement. But this area is traditional Din territory regardless of settlements and boundaries. It is Din Bikeyah, Navajo homeland since time immemorial.

The first time I remember experiencing racism was when I was four years old. In 1982 my mother, sister, and I were shopping at the brand-new Animas Valley Mall in Farmington. We wandered around the mall, feeling excited about the stores and junk food at the food court. I felt fearful as we approached a group of white teenage boys congregated in the walkway. One blond white teen stared at me menacingly, then suddenly screamed at me. The group of white teens laughed uproariously. He had tried and succeeded in frightening me, a small child, which was a typical game that white teens played to show dominance. My mother reported the incident to the white security guards, but they made excuses for the racist bully and said he was just playing a prank. I remember being confused about what had happened, but even at such a young age I knew this wasnt acceptable behavior. This was the first of many such incidents I experienced growing up in Farmington and the Four Corners.

Twenty-five years later, in October 2007, I walked around Dillards department store in the same Animas Valley Mall. I was taking a break from the hospital after my father was rushed to San Juan Regional Medical Center in Farmington with a serious head injury. A white saleswoman trailed close behind me and periodically asked if I needed assistance. I was on my cell phone, updating my sister about my fathers condition. I remarked to her, Wow, customer service here is really great. As I said those words aloud, I realized why I was being followed: I was being racially profiled. The white, overattentive saleswoman was not there to offer me service. She was there to spy on me, to watch me, to let me know that I was unwelcome. Her behavior is another form of dominance and a continued a pattern of racism I have experienced since childhood.

In another incident, my sister and I were in the San Juan Regional emergency waiting room. A Navajo trans woman, Jamie, had just been released from the emergency room. She came and sat down with us and without fear told us her story. She said she had tried harming herself and admitted that she was an alcoholic and in and out of jail and rehab. Though her story was sad, she had a wry sense of humor. She made us laugh despite all of our unhappy circumstances. We shared humor that Native people rely on in difficult times but that may seem self-deprecating to outsiders. I hope your dad recovers, Jamie said, then she disappeared on foot onto the streets of Farmington at dawn. I was concerned for her after she left. She had just tried to harm herself. Why was she released? I thought. If she were white would she be getting better health and psychological care? I began to question the system that allowed Jamie to continue untreated, which is motivation for this study.

During my fathers hospital stay, I began critically analyzing racism and racial violence in the Four Corners, specifically when my family interacted with the hospital staff, doctors, and nurses. The doctors and nurses spoke to us with scorn and were neither supportive nor caring, efforts on their part to show their racial superiority. At times my fathers caretakers were irresponsible. One memorable moment of their negligence and maltreatment was when nurses and orderlies dropped him to the floor while moving him from his bed after his neurosurgery! If we had not assertively advocated for his care, he would have been treated much worse.

Next page