Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

We hope you enjoyed reading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

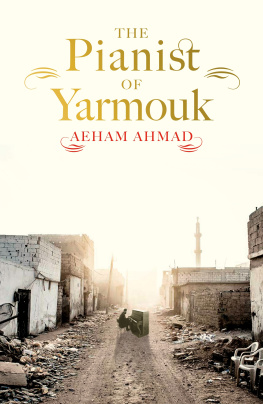

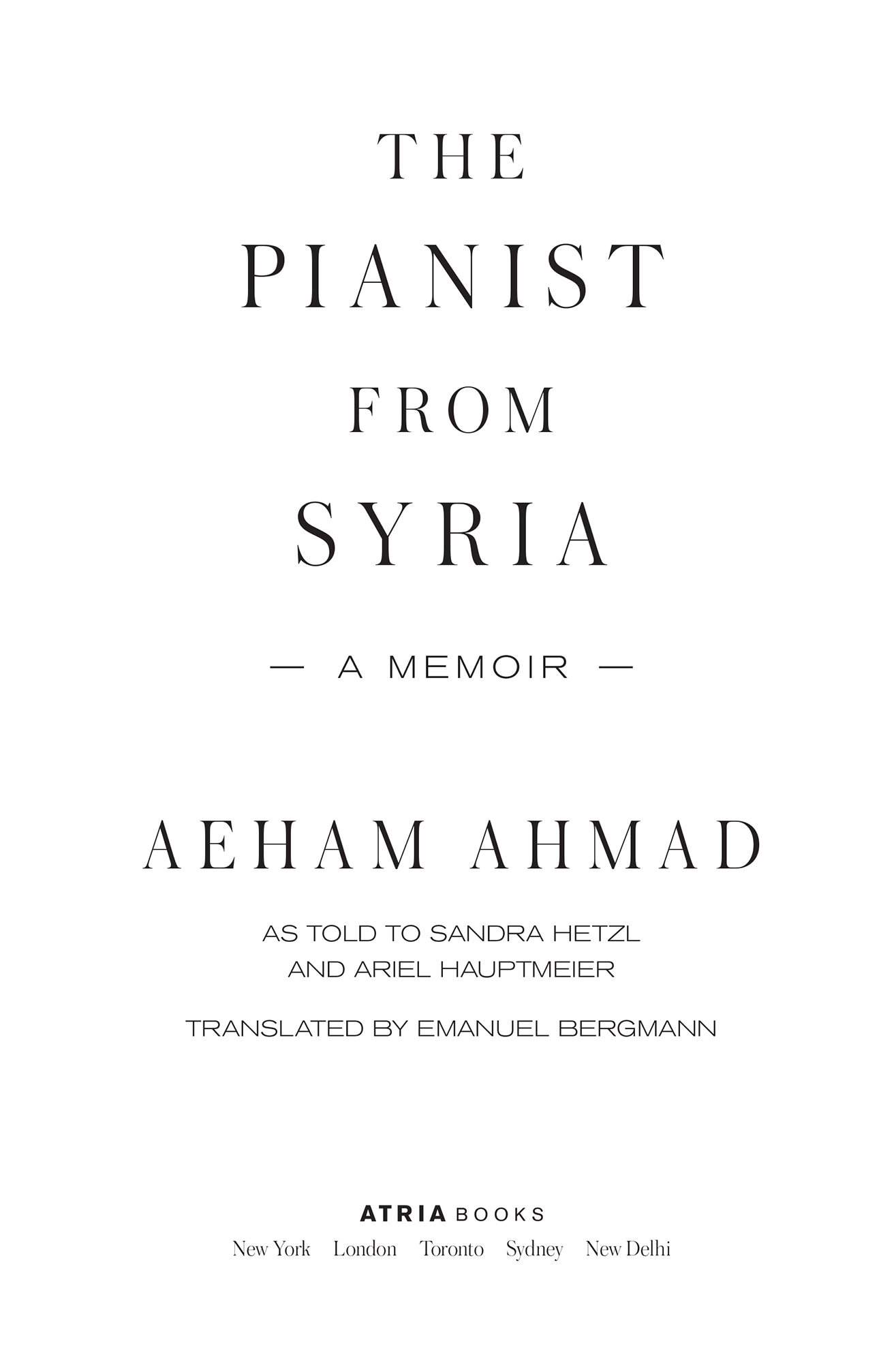

Copyright 2017 by S. Fischer Verlag GmbH

English language translation copyright 2019 by Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Translation by Emanuel Bergmann

Originally published in Germany in 2017 by S. Fischer Verlag as Und die Vgel werden singen

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Atria Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Atria Books hardcover edition February 2019

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Certain names and identifying characteristics have been changed.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Joy OMeara

Jacket design by Rodrigo Corral Design

Jacket images Reuters/Zohra Bensemra; David King/Getty Images

Author photograph Gaby Gerster

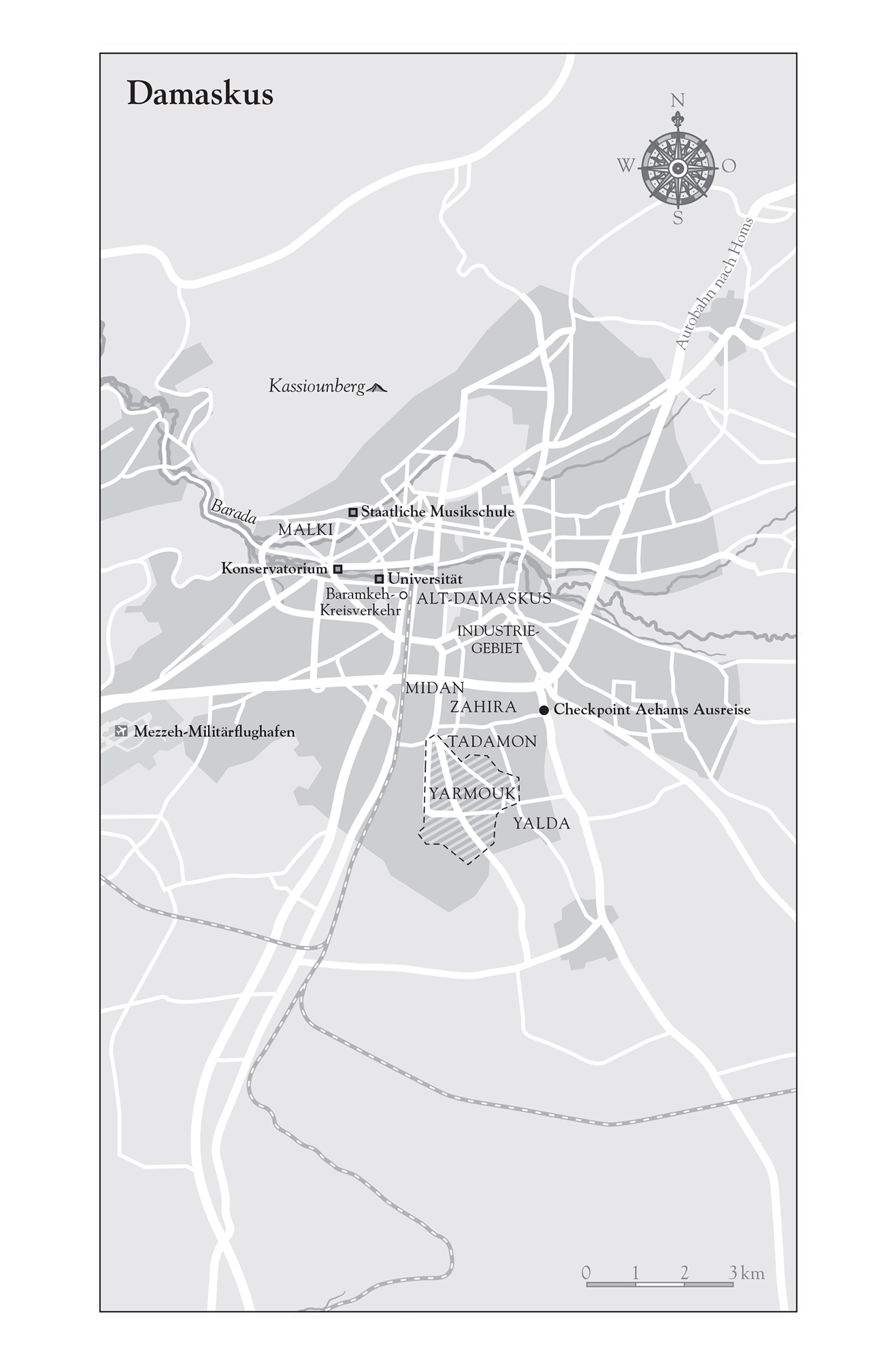

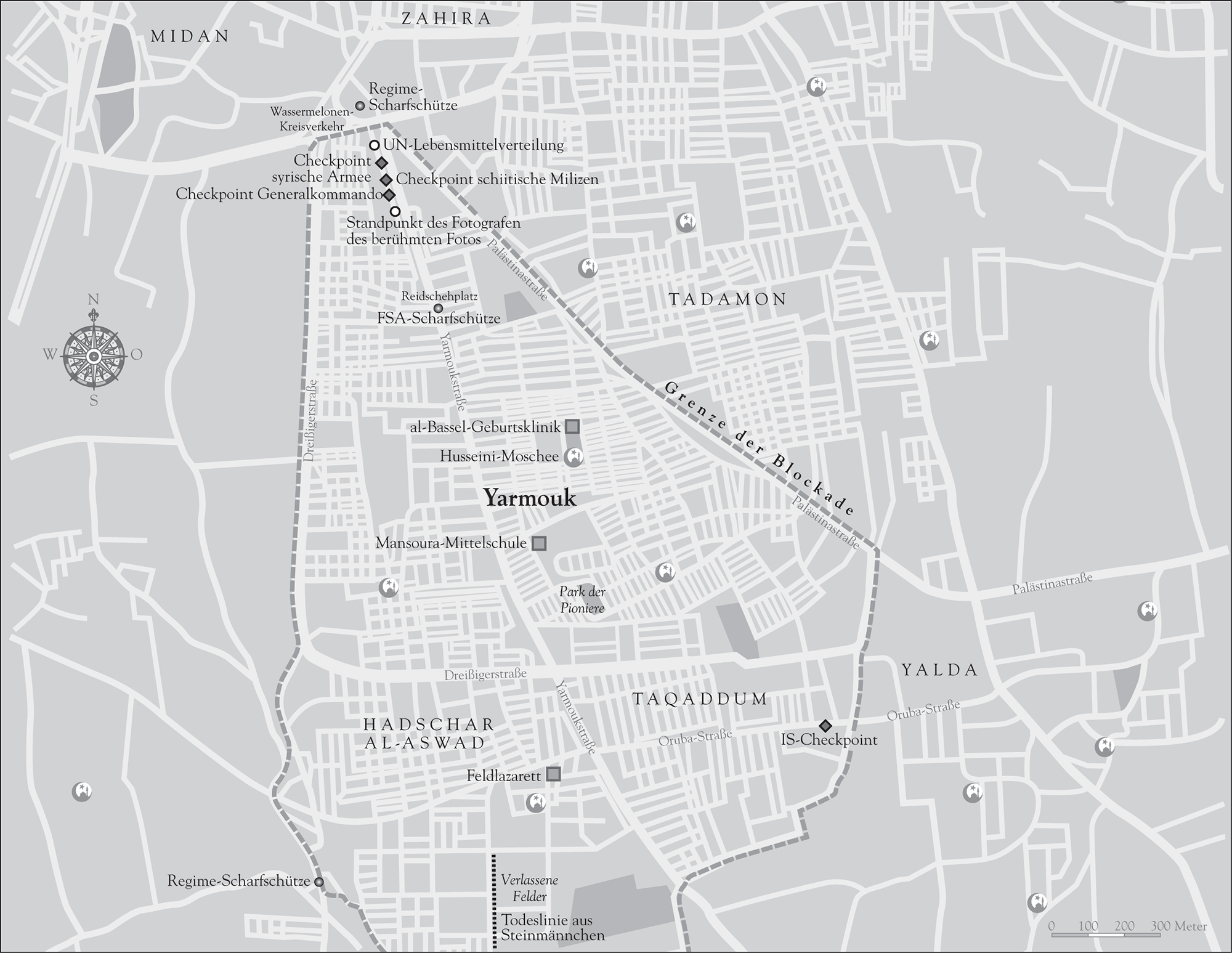

Map credit: Peter Palm, Berlin/Germany

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-5011-7349-3

ISBN 978-1-5011-7351-6 (ebook)

Dedicated to my friend Niraz Saeid, who was tortured to death in Assads prisons, and to Mahmoud Tamim, my brother, Alaa Ahmad, and to all the other political prisoners in Syria.

PROLOGUE

A photo can never really tell you what happened before or what came after. Like that picture of me sitting at a piano, singing a song amid the rubble of my neighborhood. It was reprinted by newspapers all over the world, and some people said its one of the photos that will help us remember the Syrian Civil War. An image larger than war. But when I think back to that moment, I think of another image, superimposed on all the rest, an image of three birds.

That morning before daybreak I had gone out for water, together with my friends Marwan and Raed. Getting water was backbreaking work. We had to rise early and push a 260-gallon tank on a cart to one of the last working pipes in the neighborhood, then fill up the tank and push it back home.

We lived in Yarmouk, a suburb of Damascus. The armies of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad had cut us off from the rest of the world. We had no water, no electricity, no bread, no rice. By that time, more than a hundred people had died of starvation.

After my friends and I had delivered the water to our street, I decided to get some more sleep. But a little while later, my two-year-old son, Ahmad, whispered something in my ear and then playfully poked his tiny finger into my eye. Ouch! I jumped out of bed. Clearly, I wasnt going to get any more rest.

I decided to heat up some water with cinnamonwe had run out of coffee and tea a long time ago. But there was plenty of cinnamon, ever since a group of militants had stormed a local spice depot. It hadnt seemed like such a bad haul at first, all this cinnamon, but think about it: Who needs cinnamon when you dont even have bread or sugar? Thats why it was ridiculously cheap.

Several months earlier, a few young men from the neighborhood had started a music group. We had been performing out in the streets, standing around my upright piano. Every day, we hauled it out on a cart, carefully steering it through the rubble. We sang to escape the ever-present hunger that was gnawing at us. Our performances were popular on YouTube, but the people in my neighborhood could barely be bothered. And who can blame them? When youre hungry, you cant think about anything else.

On that day, the two of us had agreed to meet with a photographer named Niraz Saied. Marwan and I began pushing the piano, which was unbelievably heavy! Usually, there were six or seven of us carefully maneuvering it through the torn-up streets. We turned onto Palestine Street, which had once been a bustling commercial center and was now deserted.

The damage there was staggering. The ruined buildings were like concrete skeletons, giant tombstones reaching into the sky. Entire walls had been torn off, revealing the insides of various apartments, with pipes and cables sticking out. The street was littered with heaps of rubble, with weeds growing among them.

I sat down at the piano and thought about what I should sing. I had written dozens of songs in the past few months; they had simply poured out of me. Then I remembered a poem, scribbled on a piece of paper, that a man had given me a few days earlier.

His name was Ziad al-Kharraf. In the old days, he sold honey in our neighborhood. He was very cultured and educated, and he used to be quite wealthy. I knew him only in passing. Ziad had a doctorate, but I dont know in what. I do know that the honey was merely his hobby. He used to take trips to the hills outside of town, to meet with local beekeepers. Sometimes he even went abroad, to countries like Yemen, where he would sample new blends of honey. But that was then. Before the war.

Ziad had written the poem for his wife. She had been in the last weeks of pregnancy, and had transit papers for Damascus so that she could give birth to her child there. But something had gone wrong at the checkpoint: the soldiers wouldnt let her pass. Apparently, some bureaucrat had misspelled her name. She had to spend hours waiting while they tried to correct the error. When it became too much for her, she collapsed and fell onto her stomach. She died on her way to the clinic. The baby survived.

Ziad had loved his wife more than anything. They had married for love; it wasnt an arranged marriage. His wife had been his best friend. They had three daughters. Their new baby was their first son.

As the photographer was setting up his camera, a woman appeared carrying a tray. She had decided to make coffee for us, using the last bit she had, which she had saved for a special occasion. She wanted to share it with us and listen to the music. What youre doing is very important, she said, pouring me a cup. I smiled at her with immense gratitude, savoring the wonderfully bitter taste of the coffee.

Next page

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.