About the Author

Aeham Ahmad, born in Damascus in 1988, grew up in Yarmouk, a suburb of Damascus. From the age of four onwards his father encouraged his musical talent and at seven he received piano lessons at the Arab Institute in Damascus. He later studied music education in Homs and worked as a music teacher.

In 2015 he was forced to flee to Germany because of the war in Syria. Today he lives with his family in Wiesbaden and gives concerts all over Europe. In December 2015, Ahmad was awarded the International Beethoven Prize for Human Rights.

This is his first book.

Aeham Ahmad

THE PIANIST OF YARMOUK

As told to Sandra Hetzl and Ariel Hauptmeier

Translated by Emanuel Bergmann

MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Germany as Und die Vgel werden singen by S. Fischer Verlag 2017

First published in the United States as The Pianist from Syria by Atria Books 2019

First published in Great Britain as The Pianist of Yarmouk by Michael Joseph 2019

Copyright S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, 2017

English language translation copyright Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2019

Translation by Emanuel Bergmann

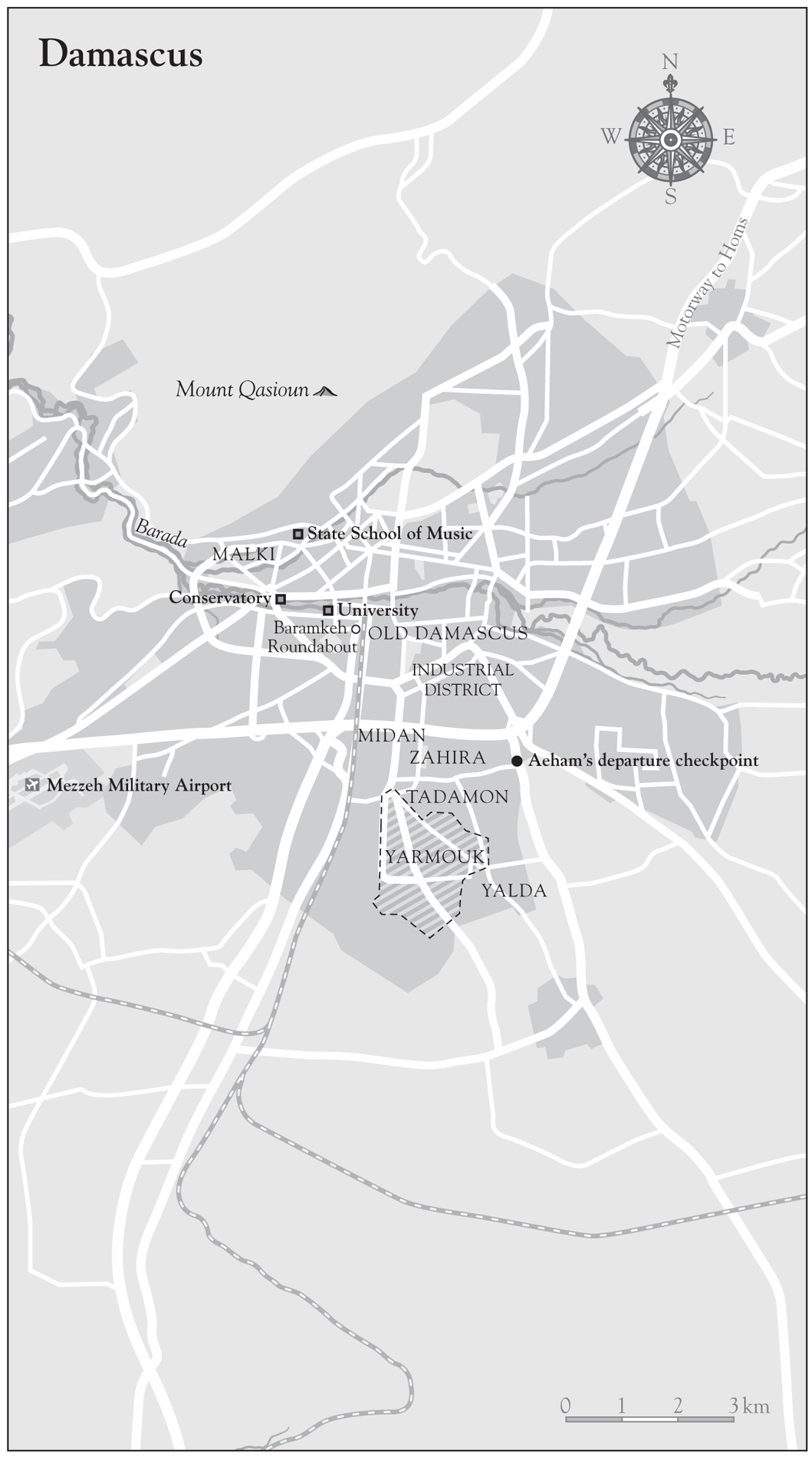

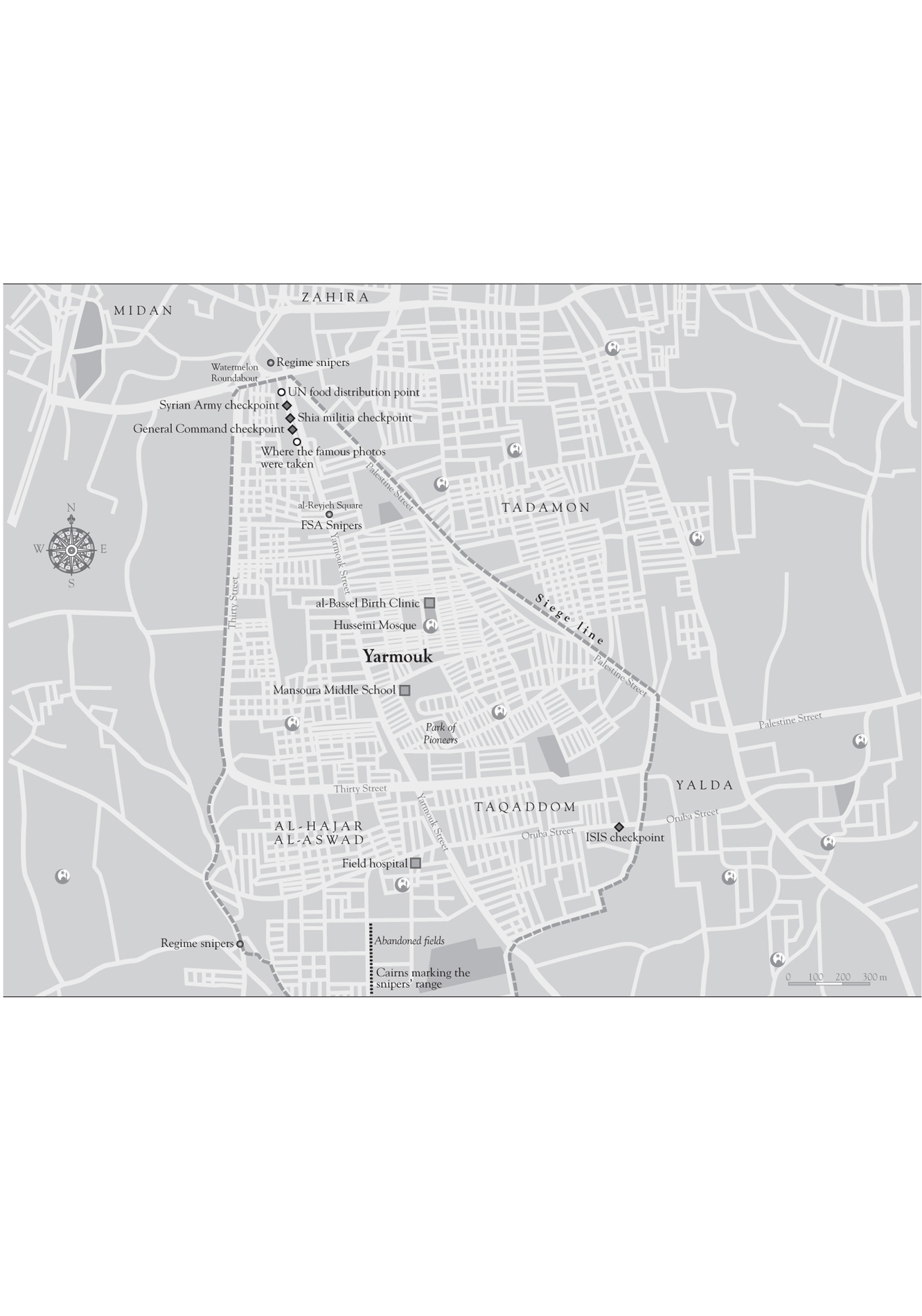

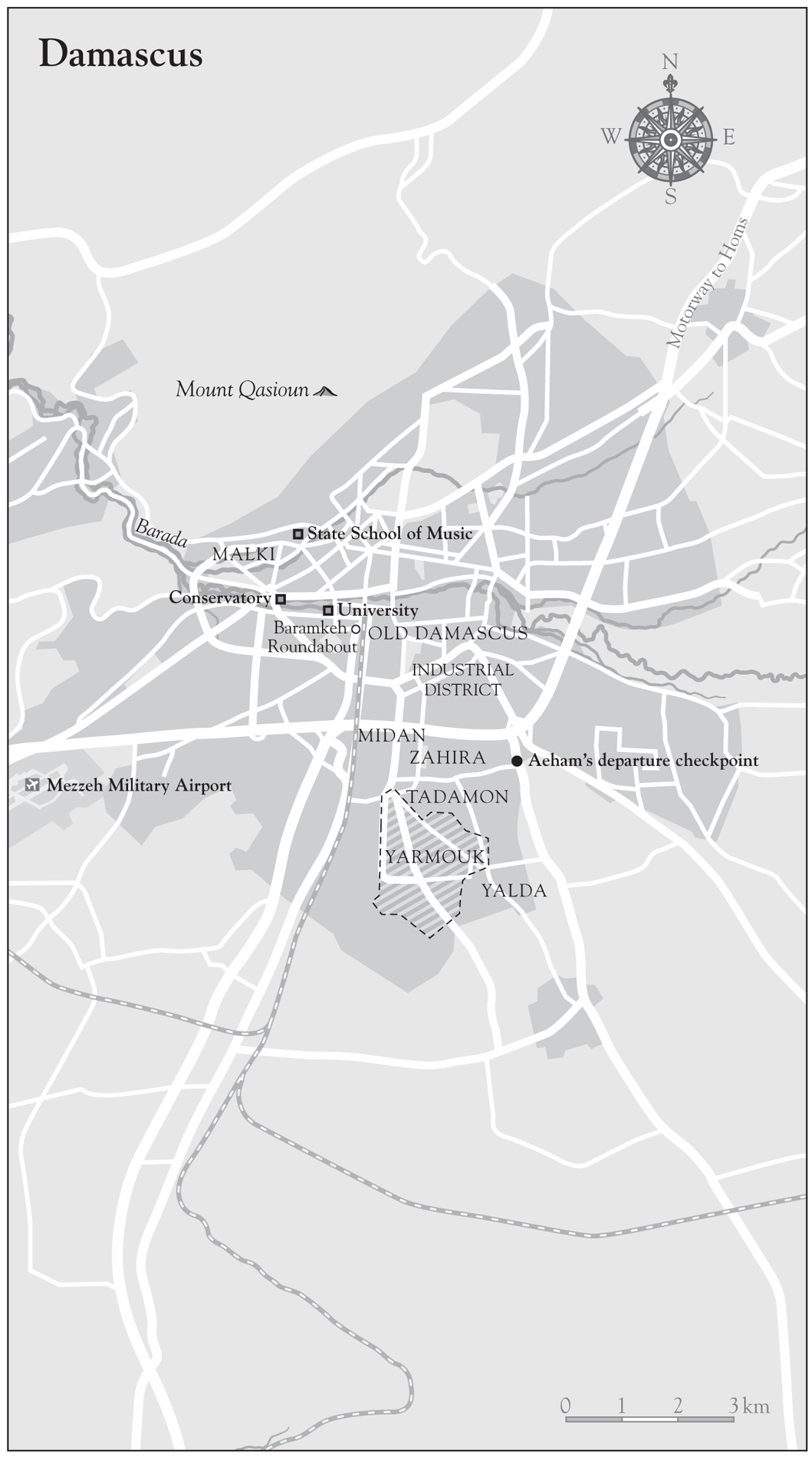

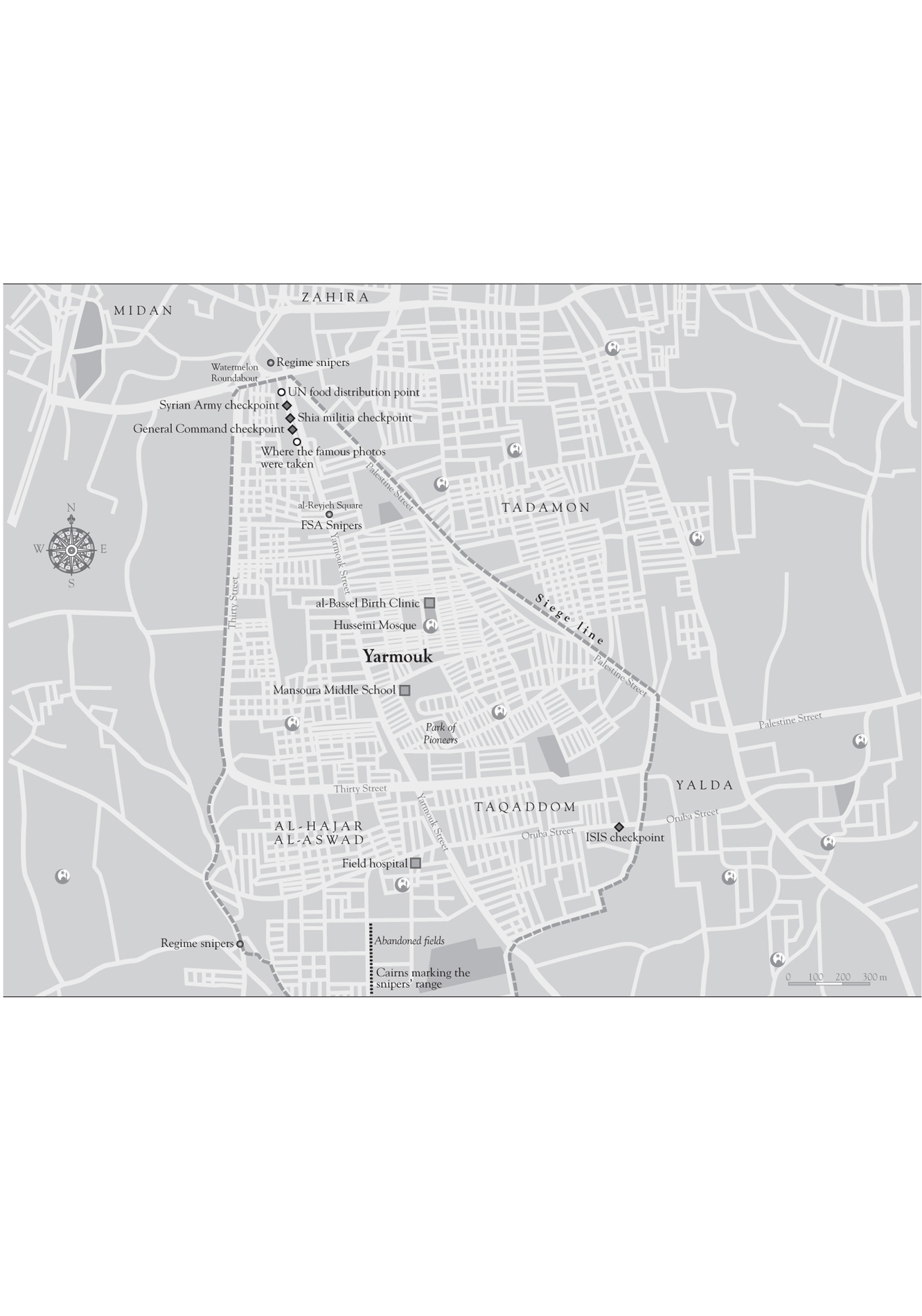

Map credit: Peter Palm, Berlin/Germany

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Image Credits: Landcape Andy Spyra/LAIF, Camera

Press, London and man at piano Getty Images

Certain names and identifying characteristics have been changed.

ISBN: 978-0-241-34754-6

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Dedicated to my friend Niraz Saied, who was tortured to death in Assads prisons and to Mahmoud Tamim my brother, Alaa Ahmad and to all the other political prisoners in Syria.

Prologue

A photo can never really tell you what happened before or what came after. Like that picture of me sitting at a piano, singing a song amid the rubble of my neighbourhood. It was reprinted by newspapers all over the world, and some people said its one of the photos that will help us remember the Syrian Civil War. An image larger than war. But when I think back to that moment, I think of another image, superimposed on all the rest, an image of three birds.

That morning, before daybreak, I had gone out for water, together with my friends Marwan and Raed. Getting water was back-breaking work. We had to rise early and push a 260-gallon tank on a cart to one of the last working pipes in the neighbourhood, then fill up the tank and push it back home.

We lived in Yarmouk, a suburb of Damascus. The armies of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad had cut us off from the rest of the world. We had no water, no electricity, no bread, no rice. By that time, more than a hundred people had died of starvation.

After my friends and I had delivered the water to our street, I decided to get some more sleep. But a little while later, my two-year-old son, Ahmad, whispered something in my ear and then playfully poked his tiny finger into my eye. Ouch! I jumped out of bed. Clearly, I wasnt going to get any more rest.

I decided to heat up some water with cinnamon we had run out of coffee and tea a long time ago. But there was plenty of cinnamon, ever since a group of militants had stormed a local spice depot. It hadnt seemed like such a bad haul at first, all this cinnamon, but think about it: who needs cinnamon when you dont even have bread or sugar? Thats why it was ridiculously cheap.

Several months earlier, a few young men from the neighbourhood had started a music group. We had been performing out in the streets, standing around my upright piano. Every day, we hauled it out on a cart, carefully steering it through the rubble. We sang to escape the ever-present hunger that was gnawing at us. Our performances were popular on YouTube, but the people in my area could barely be bothered. And who can blame them? When youre hungry, you cant think about anything else.

On that day, Marwan and I had agreed to meet with a photographer named Niraz Saied. We began pushing the piano, which was unbelievably heavy! Usually, there were six or seven of us carefully manoeuvring it through the torn-up streets. We turned onto Palestine Street, which had once been a bustling commercial centre but was now deserted.

The damage there was staggering. The ruined buildings were like concrete skeletons, giant tombstones reaching into the sky. Entire walls had been torn off, revealing the insides of various apartments, with pipes and cables sticking out. The street was littered with heaps of rubble, with weeds growing among them.

I sat down at the piano and thought about what I should sing. I had written dozens of songs in the past few months; they had simply poured out of me. Then I remembered a poem, scribbled on a piece of paper, that a man had given me a few days earlier.

His name was Ziad al-Kharraf. In the old days, he sold honey in our neighbourhood. He was very well-educated and cultured, and he used to be quite wealthy. I knew him only in passing. Ziad had a doctorate, but I dont know in what. I do know that the honey was merely his hobby. He used to take trips to the hills outside of town, to meet with local beekeepers. Sometimes he even went abroad, to countries like Yemen, where he would sample new blends of honey. But that was then. Before the war.

Ziad had written the poem for his wife. She had been in the last weeks of pregnancy, and had transit papers for Damascus so that she could give birth to her child there. But something had gone wrong at the checkpoint: the soldiers wouldnt let her pass. Apparently, some bureaucrat had misspelled her name. She had to spend hours waiting while they tried to correct the error. When it became too much for her, she collapsed and fell onto her stomach. She died on her way to the clinic. The baby survived.

Ziad had loved his wife more than anything. It wasnt an arranged marriage; they had married for love. His wife had been his best friend. They had three daughters. Their new baby was their first son.

As the photographer was setting up his camera, a woman appeared carrying a tray. She had decided to make coffee for us, using the last bit she had, which she had saved for a special occasion. She wanted to share it with us and listen to the music. What youre doing is very important, she said, pouring me a cup. I smiled at her with immense gratitude, savouring the wonderfully bitter taste of the coffee.