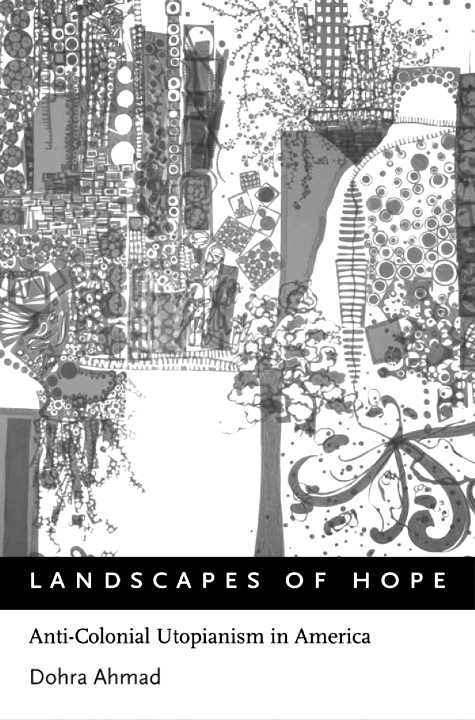

Dohra Ahmad - Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America

Here you can read online Dohra Ahmad - Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Dohra Ahmad: author's other books

Who wrote Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This page intentionally left blank

DOHRA AHMAD

For my father and mother

This page intentionally left blank

I have dedicated this book in part to Equal Ahmad, the first utopian thinker I knew and one of the most intellectually grounded and resolutely optimistic I have yet encountered. It was from him that I came to know that better worlds are possible, and that they can only come into being through the full selfdetermination of all people-two of the principles upon which I have based this study. Like many of the figures who appear here, he had a long-standing commitment to solidarity among liberation movements. Even at the end of his life, when his country of birth and his final homeland brandished at each other the world's most destructive weapons, he never took refuge in despair.

The idea for this study first came together during the dim and difficult months following his unexpected death in May of 1999. It took shape with the guidance of my wonderful graduate advisors: Ann Douglas, Jean Howard, Robert O'Meally, Bruce Robbins, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, and Gauri Viswanathan. I thank all of them for their inestimable contributions to my thinking about the topics here, as well as about literature and culture more generally. I also benefited enormously from the careful reading and consideration of Amanda Bowers, Jolisa Gracewood, Amy King, Michael Malouf, Gary Okahiro, Marisa Parham, Lily Shapiro, Sandhya Shukla, Robin Var- ghese, and the members of Columbia's Postcolonial and Cultural Studies dissertation group. Orin Herskowitz read and commented on every line, well before I could consider any of them remotely fit for wider consumption. Tanya Agathocleous, Sarah Cole, and Amy King offered invaluable advice on publication. Shannon McLachlan championed the book from the beginning and provided helpful feedback at every turn. I am grateful as well to the anonymous reviewers for Oxford University Press and the Journal of Commonwealth Literature for their thoughtful comments, and to Shannon McLachlan and Jon Thieme, respectively, for facilitating their reviews. In the final stages, Erin Fiero dove valiantly into the world of indexing, and Paul Hobson patiently guided the book through production.

A portion of chapter 2 appeared in an earlier version as "`More than Romance': Genre and Geography in Du Bois' Dark Princess" in English Literary History 69:3 (2002): 775-803. A portion of chapter 3 appeared as "The Home, the World and the United States: Young India's Tagore" in Journal of Commonwealth Literature 43:1 (2008): 23-41. I also appreciated the opportunity to present some of the ideas at panels organized by the Society for Utopian Studies, the Rutgers Comparative Literature Department, and the Modern Language Association's Division of Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Literature. The staff of Butler Library and Mule Cafe provided congenial places to work. The St. John's English Department has been an ideal institutional home for me: collegial, humane, and intellectually vibrant. Most importantly, during the years of working on Landscapes of Hope I have been lucky to have around me an immensely supportive group of family and friends who entertained my daughters, cooked me food, pulled me out of the doldrums of early writing and revision, and generally gave the most material substance to my thoughts on the importance of community. Foremost among them are Orin Herskowitz, Eliya Sage Ahmad, Melina Rose Ahmad, and Julie Diamond; to those four go my deepest gratitude and love.

This page intentionally left blank

This page intentionally left blank

The impossible gives birth to the possible.

-Karl Mannheim, Ideology and Utopia

On September 21, 1917, New York's Intercollegiate Socialist Society sponsored a joint lecture by local luminary W. E. B. Du Bois and exiled Indian nationalist Lala Lajpat Rai. The lecture provided an opportunity for a truly global analysis of economic and cultural oppression, and both men rose to the occasion. Despite his central importance within American sociology and African-American historiography, Du Bois had long been committed to thinking about slavery, colonialism, and their enemies in a transnational frame. Lajpat Rai's focus had previously been more limited-to India and especially the Punjab-but during his exile years in New York his particular brand of nationalism developed a cosmopolitan character as he enlisted the solidarity of Du Bois as well as Irish nationalists and American labor organizers. "The problem of the Hindu and of the negro and cognate problems are not local, but world problems," he stated at that event, anticipating sentiments if not vocabulary that would recur throughout the century.' Elaborating on Du Bois's famous formulation regarding "the problem of the color line," Lajpat Rai reflected on the forces that had produced so many hyphenated experiences in the United States and abroad.

My aim in Landscapes of Hope is to give substance and context to Du Bois's and Lajpat Rai's brief encounter. The deeper story of their cooperation brings out both the parallels and the divergences between two groups that shared the general goal of emancipation for the colored people of the world. Despite the opening connection between Du Bois's elegantly phrased problem and Lajpat Rai's dysphonic one, in this book I am less interested in problems than solutions. Du Bois's and Lajpat Rai's Socialist-sponsored joint lecture represents one emblematic moment during a period in which anticolonial organizing developed in a holistic, worldwide form. Their cooperation belongs to the same tradition that fostered the Association of Oppressed Peoples, the 1911 Universal Races Congress, and the 1927 Brussels Congress of Oppressed Nationalities; this last event brought together an illustrious group including Jawaharlal Nehru, Lamine Senghor, Ho Chi Minh, Madame Sun Yat Sen, Romain Rolland, and Albert Einstein. Written texts reflected and bolstered the emerging transnationalism: Du Bois's 1927 novel Dark Princess envisioned the post-colonial order taking the form of a supranational "world of colored folk," while Lajpat Rai's New York-based periodical Young India reported not only on its titular landmass but on promising anticolonial developments in Ireland, Egypt, and China.' Throughout this sadly ephemeral period, exile nationalism merged with metropolitan dissent to forge a transformative politics that aimed to transcend race and nation, a forgotten but significant precursor to the "globalization from below" that Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri have called for in our own century.

During this time of intimidating potential, the architects of decolonization carried out the exhilarating work of imagining independent states. Du Bois and Lajpat Rai, along with Pauline Hopkins, Rabindranath Tagore, Sarojini Naidu, and others, did this by marshaling the goals and methods of utopian fiction. How else could one navigate the vast realms of possibility that lay ahead? Like Milton's hapless mortal protagonists at the end of Paradise Lost, "the world was all before them." In response, the writers I study here made use of their literary prowess to create better worlds that they and their readers could inhabit together. Through fiction, poetry, and reflective essays, they began the process of constructing a better future. Lajpat Rai cobbled together an eclectic mix of documents-the latest poems of Mohammed Iqbal, Sarojini Naidu, and Rabindranath Tagore; ancient art reproductions; reports on nationalist activities in Amritsar, London, and Minneapolis; and sympathetic patriotic lyrics by dead American abolitionist poets-into the transnational periodical Young India. In so doing, he and his multi-national editorial collective circulated every month a vibrant and often contradictory image of an ideal independent India. Pauline Hopkins, in her messianic novel Of One Blood, carries her American-born hero to Ethiopia's Hidden City of Telassar, where he fulfills his unknown destiny by bringing the cloistered utopia into the modern world. W. E. B. Du Bois in Dark Princess audaciously merges India, Africa, and the American South to produce a global Black Belt on the verge of true emancipation.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America»

Look at similar books to Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.