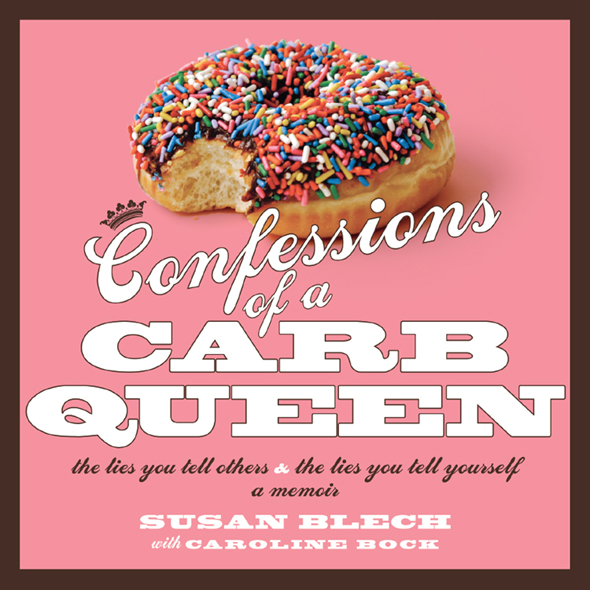

Notice

Mention of specific companies, organizations, or authorities in this book does not imply endorsement by the publisher, nor does mention of specific companies, organizations, or authorities imply that they endorse this book. This book also contains advice and information pertaining to health care. It is not intended to replace medical advice, and you should seek your physicians advice before beginning any medical program or treatment, including what is described in this book. The publisher and the author disclaim liability for any medical outcomes that may occur as a result of applying the methods suggested in this book.

To our father and mother,

Morris and Louise Blech,

with love

Contents

Authors Note

Im not a weight loss expert, meaning Im not a doctor or a nutritionist or psychologist or fitness guru. Im the anti-expert expert. Im the expert about what worked for me in losing weight and about why I sometimes failed and binged, and still do, though less and less now. No one is perfect, least of all me. Im on a journey. Ive written this book with my sister because for a long time I felt very alone, and no one should feel that alone and scared and ashamed.

Some names and identifying features of certain individuals have been changed in order to protect their privacy. Remembered scenes and dialogues are, well, remembered, and recalled as memory serves.

This is my story. Its sometimes shocking, sometimes funny and sad. Im sharing my life with you, and thats how my life is sometimes.

Prologue

My very first food memory involves the most basic of ingredients: bread, butter, and sugar. Its the summer of 1973. Richard Nixon is president. A hotel, the Watergate, is in the news. American prisoners of war come home from Vietnam. And Im 8 years old. I make a white bread, yellow butter, and white sugar sandwich with my next-door neighbor, Cassie. Shes a year older and shows me how.

I climb on the high kitchen chair. I take out a whole loaf of bread from the bread box and press the butter into the center of one slice. The bread tears apart.

There arent any adults around to come to my aid. Nana didnt show up today, too hot for her. My sister is supposed to be watching us. Shes 10, and shes probably in our bedroom, reading a book. My brothers are glued to the TV in the living room; the 4 oclock movie is on. Its Godzilla Week.

We live at the end of the block, in a small white cape with the hopscotch painted on the driveway. If you ask any of our neighbors, theyll say were the house without a mother.

The kitchen, with its orange-flowered wallpaper and cracked gray and white linoleum, is just big enough for Cassie and me. The counter, where we eat breakfast and lunch, separates the kitchen from the dining room. A radio, covered in fingerprints, and a toaster, powdery with crumbs, clutter the counter. Were not supposed to stick knives into this old toaster, but we do; how else would the toast ever get out?

Containers marked Flour, Sugar, and Tea crowd next to half-eaten cereal boxes. The refrigerator groans and creaks in the center of the kitchen. At night, it sounds like a monster is eating our food. The stove is stuffed with pots and pans that clatter out every time the oven door is opened. Dishes multiply in the sink; laundry does the same thing in the basement; its amazing, says my father.

Around the other side of the kitchen, I share a pink bedroom with my sister. My brothers share a blue bedroom. My father has his own bedroom. At the end of the hallway is the bathroom. In the mornings, we all battle for first in. Later, when were teenagers, my sister and older brother will move upstairs, and well each have our own bedroom. Ill stay in the downstairs bedroom, closer to my father. Hell ruminate for years about adding another bathroom, but he never will.

Right now, its 1973, and all I want is another white bread, butter, and sugar sandwich before my father gets home. I pull out the large container marked Sugar and shake it over the bread and butter. The sugar scatters across the Formica counter and onto the floor, alive like ants. Cassie and I scrunch the sugar under our sneakers, pouring out more. The countertop and floor and my hands are sticky. With another attempt, I spread a layer of sugar on the bread like a fine white snow. I press one slice of bread on top of the other. Cassie laughs. My sandwich is lopsided.

Cassie has very long, straight brown hair that her mother braids every day. All this summer shes wearing a floppy white beach hat like Gilligan. She has buckteeth and is the youngest of 10. Her older brothers and sisters are hippies, says our father. Even though Cassies a year older, Im taller. My hair is long, too, but thick, wavy, knotted in places I cant get to, a chestnut brown streaked with reds and never in nice braids like hers.

In my kitchen, I pull out the bread knife with its jagged blade. Cassie says to be careful. In her house, shes not even allowed to use a knife so big and sharp. I cut the sandwich in half, but one side is twice as big as the other.

I always do things the hard way, I say, repeating what my father always says about me, not wanting Cassie to see that Im upset. We each stuff a deformed half in our mouths.

W hen we were little, housekeepers lived with us. But now, David is 7, and Im 8, Mark, 9, and Caroline, 10, and shes in charge. If she sees what a mess were making, shes going to get mad. Shell make me clean it up immediately. Cassie and I have to work fast.

When my mother comes home, Caroline wont be able to boss me around. But Mommy has to get better first. She had a stroke when I was 112. She lives in the Hudson River State Psychiatric Hospital. Ross Pavilion. Poughkeepsie, New York. We send birthday, Christmas, Easter, Mothers Day, and Halloween cards to her there.

Every few weeks, we visit. I cant wait to see my mother. Caroline and I always prepare spaghetti with tomato sauce, her favorite dish. We pack it in a bowl, cover the bowl with plastic, and bring a plate, a fork, and a dishcloth to tuck under her chin, like were going on a picnic.

The last part of the 90-minute trip upstate is a long, curving driveway lined with trees. The hospital is built on a hill. The four of us bound up the marble stairs. My father has to catch up. He says were too fast. At the top of the stairs, if I turn around, are mountains, the tops of apple trees holding up billowy clouds. The doors swing open and the smell of pee and bleach and cigarettes hits me. I take a step back. Every time, I hope that today my mother will walk out those doors and that we dont have to walk in.

Inside the lobby, the sunlight sifts in through windows covered in wire mesh. The lobby is crowded. Everyone smokes. The waxed marble floor is dirty, smudged with cigarette butts. Other patients shuffle along in slippers or in sneakers without laces, wearing layers of sweaters, even though its so hot I feel dizzy and light-headed. They look blank and scared like the people in the Godzilla movies my brothers like to watch. A few hound us for cigarettes. I hide behind my father. He has to yell at them to go away.

My father finds us an empty corner of vinyl chairs. The chairs are orange and sticky. Candy wrappers and rolled-up newspapers and torn cigarette cartons are wedged into the seats. My father tells us to sit there and not to move. He strides to the elevator and it swallows him up.