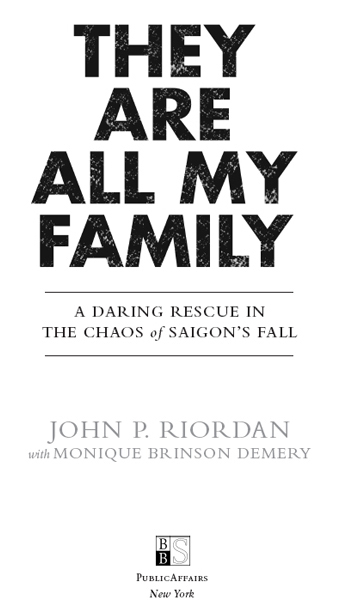

Praise for They Are All My Family

In the chaos of a frenzied war, in the mounting gyre of fear, brutality, and cowardice, one man steps forward to offer 106 terrified souls safe passage from the hellfire. What human impulsewhat valor, grit, and graceled John Riordan to countermand his orders, risk personal danger, and set himself on a perilous course to save lives in the last anarchic days of the Vietnam War? They Are All My Family is a thrilling account of a young banker who had every opportunity to do exactly what his country was doingcut his losses and runand yet he did the very opposite. Told with gripping detail, a white-knuckle sense of urgency, and, above all, a very large heart, this is a story that recalls Schindlers List or The Pianist or The Siege of Krishnapur. It is a triumphant tale.

Marie Arana, author of Bolvar: American Liberator and American Chica

Copyright 2015 by John P. Riordan

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs, a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

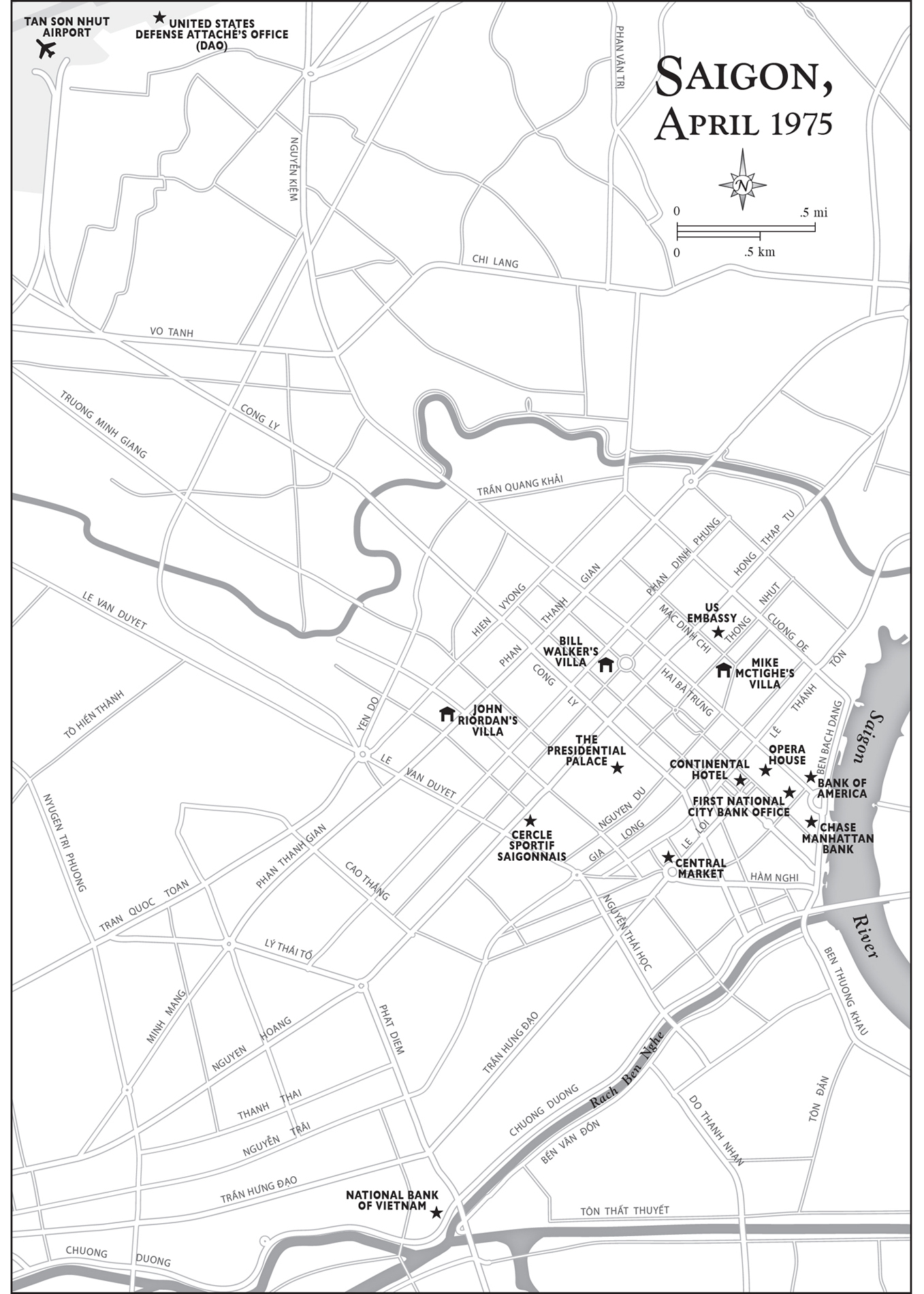

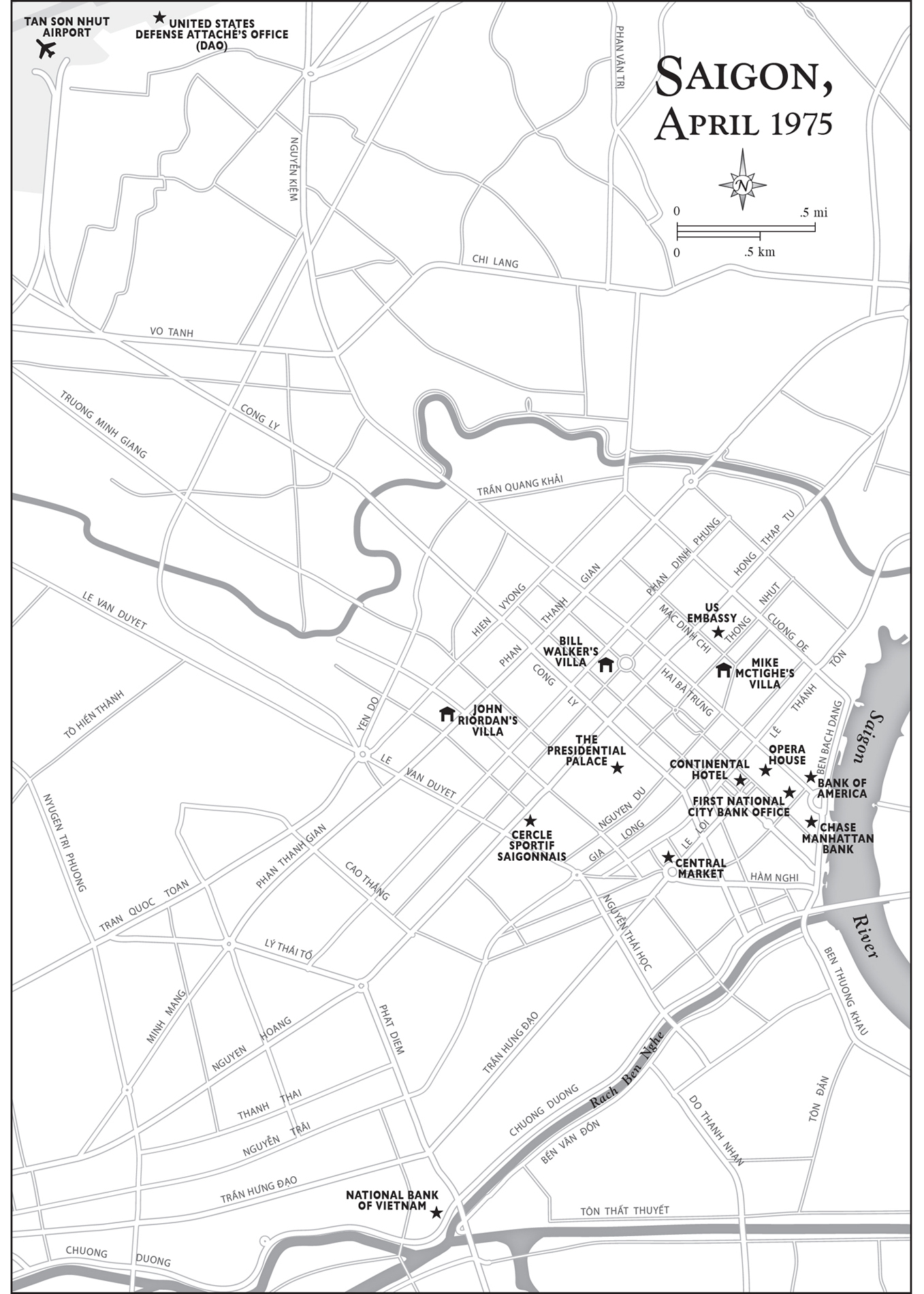

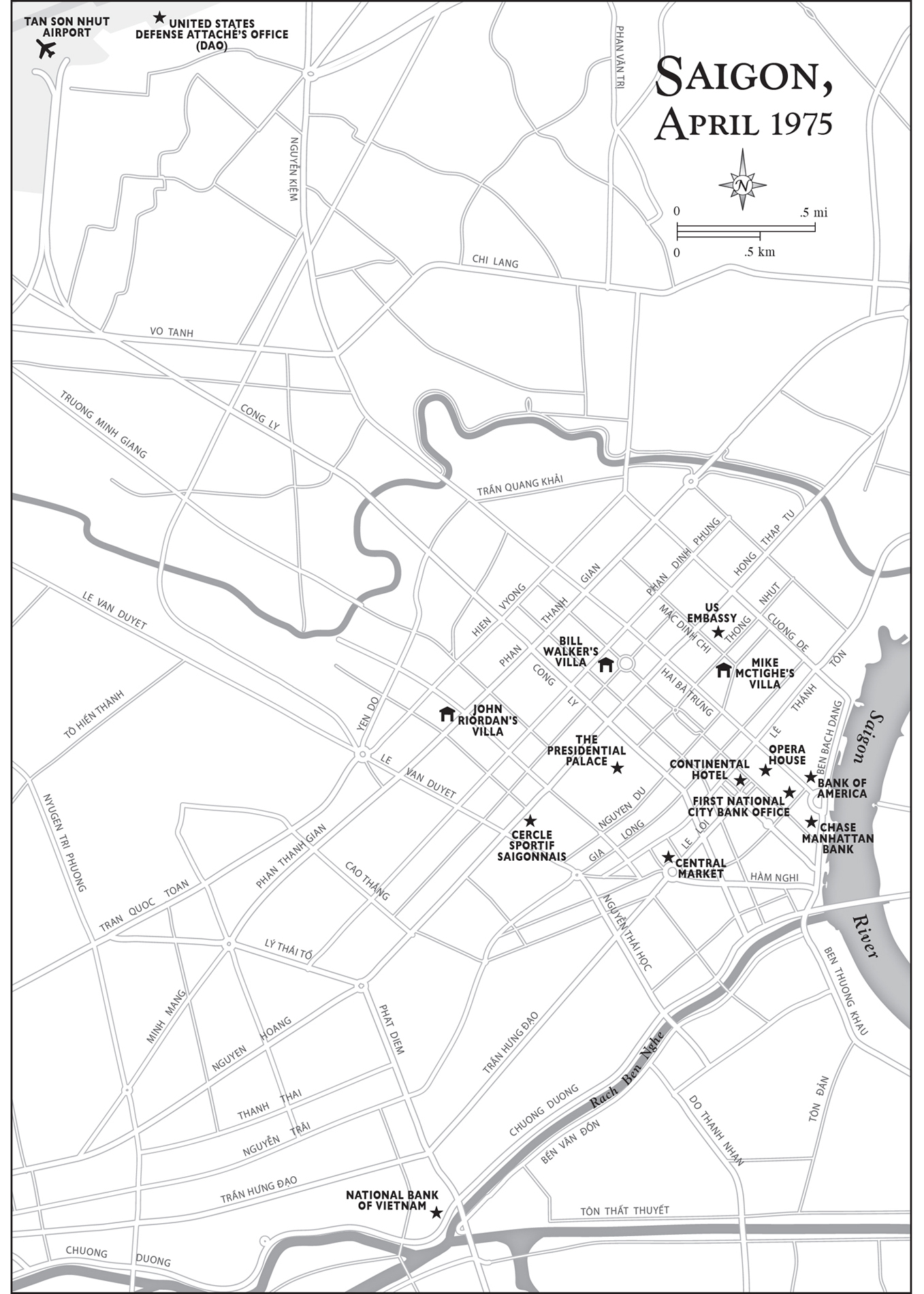

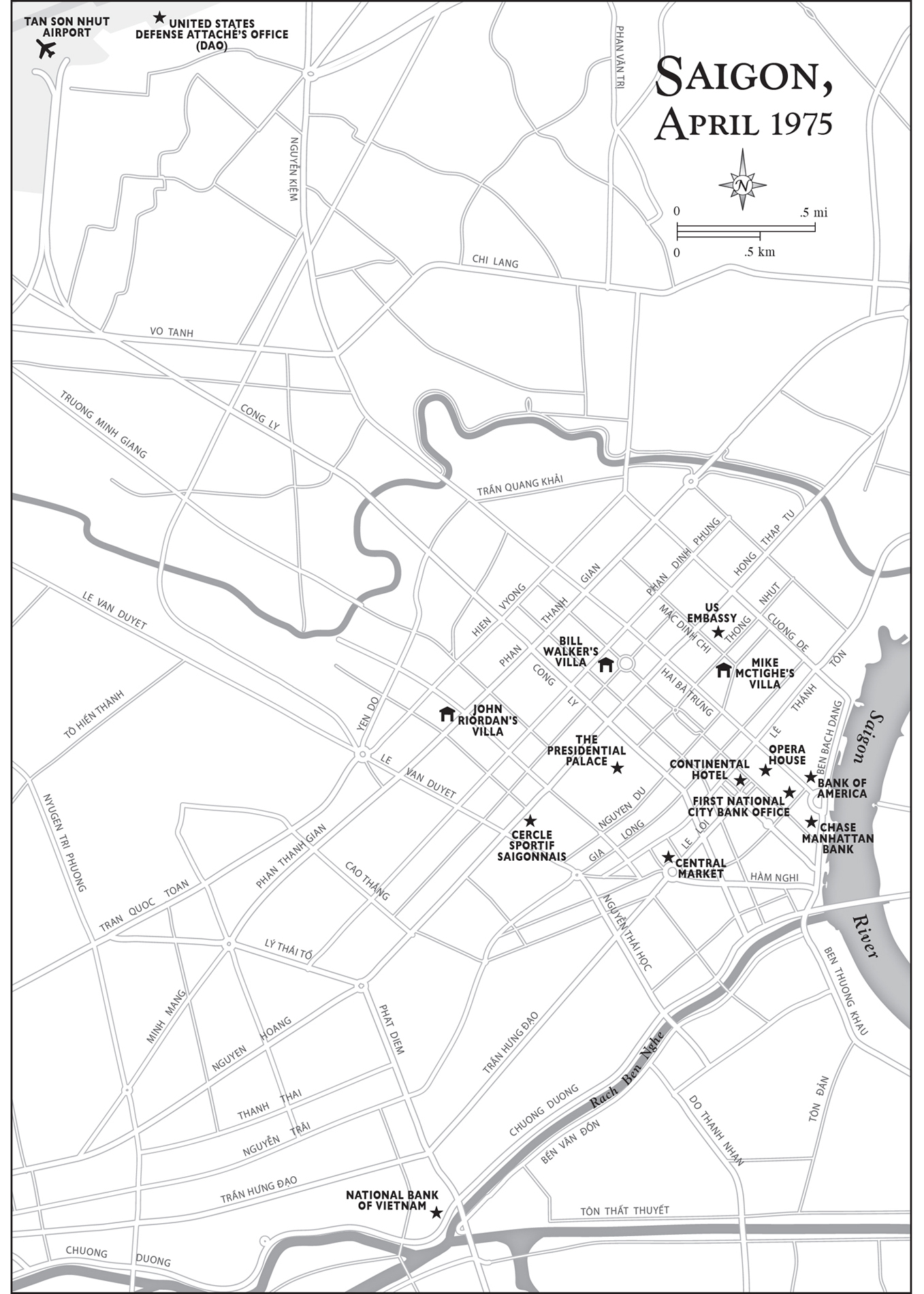

The map of Saigon, April 1975, on p. viii is based on maps dating back to 1969 and includes names and locations from the authors memories.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Riordan, John P., author.

They are all my family : a daring rescue in the chaos of Saigons fall / John P. Riordan with Monique Brinson Demery. -- First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61039-504-5 (e-book) 1. Vietnam War, 19611975 VietnamHo Chi Minh City. 2. Humanitarian assistance, AmericanVietnamHo Chi Minh CityHistory. 3. Vietnam War, 19611975Personal narratives, American. 4. RefugeesVietnamHo Chi Minh CityHistory. 5. Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnam)History. I. Demery, Monique Brinson, 1976 author. II. Title.

DS559.9.S24R56 2015

959.704'3095977dc23

2014049615

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to the memory of my loving and kind parents,

William Joseph Riordan and Rosemary Murphy Riordan,

for their gentle care, saintly patience, and guidance.

Not only did they give me the greatest gift of all, life itself,

but they taught me the importance of family.

CONTENTS

I HEARD A RUMOR, I mentioned casually to the Vietnamese ticket agent at the gate. I hear Air Vietnam is going to end service into Saigon?

The young woman flinched, almost imperceptibly, and recovered quickly. Thats just a lousy rumor. Theres no truth to it, the young woman said firmly. She shook her long straight bangs out of her way and shot me an icy look. I glanced over my shoulder, but no one was behind me. I wasnt holding up any passengers. Hardly anyone was getting on that mornings flight from Hong Kong to Saigon. It was Friday, April 18, 1975.

The ticket agent handed me back a receipt for my one-way ticket into South Vietnam and forced a tight smile. Dont believe any of those rumors. She smoothed the silky panels of her ao dai. The traditional Vietnamese dress is a knee-length tunic that the flight attendants of Air Vietnam wore in a shade of blue that matched the sky above the clouds. Despite the modesty of long sleeves, and the fact that the tunic was worn over flowing, wide-legged pants, the ao dai still managed to be suggestive. Long side slits showed a peek of skin above the waist, and the thin fabric hugged every curve. The ticket agent avoided my gaze and looked past me, blankly, waiting for any other passengers to board.

Except there were no more passengers. The flight was nearly empty. I chose a window seat a few rows from the front. Although I could have sworn there were at least a few others who got on the plane with me, Ill admit I was preoccupied. It was my second flight to Saigon that week. Someone told me that when they had checked the flight manifest, my name was the only one on it.

Everything else about that Friday morning flight into Saigons Tan Son Nhut airport did seem as usual. My meal tray was distributed when the plane reached our cruising altitude. I had the ham omelet, two strips of grilled bacon, a tomato slice, and a fruit cocktail. The only reason I can recall the breakfast so clearly all these years later is because I slipped the menu into my bag as a souvenir. The Vietnamese woman drawn on the menu in orange and black ink seemed to wink at me from the cover, as if she knew exactly what I was up to.

I wasnt used to breaking rules. But thats exactly what I found myself doing by flying out of Hong Kong on a one-way ticket. It was direct defiance of my bosses at the bank. They had ordered me to stay away from Saigon, and I was heading right for it. There was not a doubt in my mind that I would be fired. There was also no doubt that it was the right thing to do. As for that lousy rumor, the one that Air Vietnam was stopping service from Hong Kong to Saigon? As it turned out, the rumor was right. My flight was the last trip the carrier would make from Hong Kong into Saigons Tan Son Nhut airport.

The strangest feeling of calm came over me the moment the planes wheels touched down on the tarmac. I was in Saigon on my own, under my own authority. Instead of feeling alone or scared, I felt fine. That feeling took me completely by surprise.

John, you no longer work for the bank, I told myself, tentatively probing the thought, the way I might test a bruise. I wanted to see how bad it would feel. But it wasnt so bad at all. I seemed to have left any fears and doubts at high altitude above South Vietnam. Logically, that made no sense. Things were, by all reasonable measures, bleak. The North Vietnamese Army was approaching, and South Vietnamese cities were collapsing faster than people could leave.

I heard horror stories of fleeing refugees dropping dead of exhaustion by the side of the road. Mothers in the countryside were handing their babies off to anyone with a white face, anyone who might get their child on a boat or a plane. The capital city of Saigon and the surrounding areas were the last refuge. No South Vietnamese citizen was allowed to leave the country. Technically all they needed was an exit visa and immigration papers. But those had proved impossible for the average citizen to get. The bank had tried. My friends and colleagues at the bank would be stranded. They would be at the mercy of the Communists unless I thought of something. That was worth getting fired for.

Next page