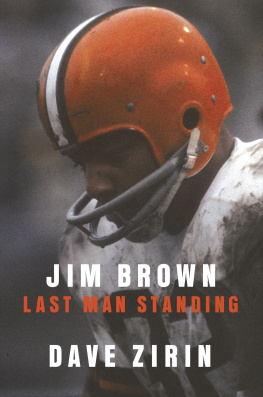

ALSO BY DAVE ZIRIN

Brazils Dance with the Devil: The World Cup, the Olympics, and the Fight for Democracy

Game Over: How Politics Has Turned the Sports World Upside Down

The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World

Bad Sports: How Owners Are Ruining the Games We Love

A Peoples History of Sports in the United States

Muhammad Ali Handbook

Welcome to the Terrordome: The Pain, Politics, and Promise of Sports

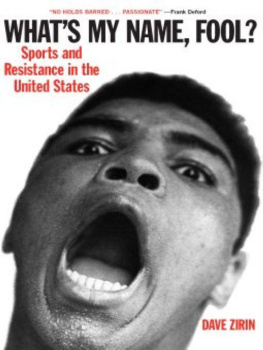

Whats My Name, Fool? Sports and Resistance in the United States

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright 2018 by Dave Zirin

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

The author gratefully acknowledges permission to reprint excerpts from the following works: Alex Haleys interview of Jim Brown in Playboy, 1968, courtesy John A. Palumbo. Off My Chest, by Jim Brown with Myron Cope, copyright 1964 by James N. Brown and Myron Cope. Used by permission of Doubleday, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Out of Bounds, by Jim Brown with Steve Delsohn, copyright 1989 by Jim Brown and Steve Delsohn. All rights reserved. Reprinted by arrangement with Kensington Publishing Corp. www.kensingtonbooks.com.

Photographs: Nick Cammett/Diamond Images/Getty Images

Blue Rider Press is a registered trademark and its colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC

Ebook ISBN: 9780698186071

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zirin, Dave, author.

Title: Jim Brown : last man standing / Dave Zirin.

Description: New York: Blue Rider Press, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017035828 | ISBN 9780399173448 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Brown, Jim, 1936 . | Football playersUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC GV939.B75 Z57 2018 | DDC 796.342092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017035828

p. cm.

Version_1

TO LIEUTENANT RICHARD COLLINS III AND SANDRA BLAND

#SayTheirNames

We always lament in the superficial media culture that there are no heroes, but that presupposes that a hero is perfect and what the Greeks have told us for millennia is that a hero isnt perfect. Heroism is the negotiation between a persons strengths and weaknesses... and sometimes its not a negotiation. Its a war.

KEN BURNS

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

IT JUST IS WHAT IT IS

Football is the closest thing we have in this country to a national religion, albeit a religion built on a foundation of crippled apostles and disposable martyrs. In this brutal church, Jim Brown is the closest thing to a warrior saint. Brown is, both statistically and according to awed eyewitnesses, perhaps the greatest football player to ever take the field. At six-foot-two and 230 pounds, running a sub-4.5 forty-yard dash, he was like a twenty-first-century Terminator sent back in time to destroy 1950s and 1960s linebackers. In the gospel of football, defensive demons like Dick Butkus, Lawrence Taylor, and J. J. Watt have carried some of that fearful mystique: transforming their opponents into quivering balls of gelatin. But on offense, the all-time great skill playersJohnny Unitas, Jerry Rice, Walter Paytonhave inspired astonishment yet never physical fear. On that side of the line of scrimmage, the list of true intimidators begins and ends with Jim Brown.

The statistics that define his time in football are still without equal. Brown played nine years and finished with eight rushing titles, a level of consistent greatness no one has come close to matching. He is the only player to average one hundred yards rushing per game over an entire career and the only running back to retire with an average of five yards every time he carried the ball. Then there is the most impressive number of all: zero. That is the number of games Brown missed over his nine years in the National Football League. It would be a stunning achievement for a placekicker. But it is especially remarkable given the ungodly workload Brown maintained and the constant punishment he took, touching the ball for roughly 60 percent of all the Cleveland Browns offensive plays.

In NFL circles, these numbers are spoken with veneration, the same way baseball writers talk about Babe Ruth or NBA fans recall Wilt Chamberlain or boxing writers speak about the young Muhammad Ali or tennis aficionados discuss Serena Williams. Babe Ruth swatted fifty-nine home runs in 1921, more homers than were hit by half the teams in baseball. In the 19611962 season, Wilt Chamberlain averaged fifty points every time he took the court, nineteen more per game than the next top scorer. Muhammad Ali fought Cleveland Williams and avoided all but ten punches in three rounds. Serena Williams has won twenty-three Grand Slams as of this writing, and her latest one, in Australia, was during her first trimester of pregnancy. These are not merely examples of great athletes. It is as if they were playing altogether different sports from their peers.

But Jim Brown was also so much more than Babe or Wilt or even Ali. He was in many respects the first modern superstar. In an era before strong sports unions, he organized his locker room to stand up to management on issues great and small, never giving an inch and earning a derisive nickname from team executives: the locker room lawyer. In an era years before Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists against racism and for human rights at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, it was Jim Brown who refused to be treated as a second-class citizen just because of the color of his skin. In a time before Muhammad Ali shook up the world by joining the Nation of Islam and refusing to fight in the Vietnam War, Brown did so much of his own shaking that Ali, in his darkest hours, turned to him for advice and support.

Brown was the first player to use an agent. He was the first superstar to successfully demand that a coach be fired and that released teammates be immediately unreleased. He was the first athlete to ever willingly quit his sport in his prime, because his manhood was more important to him than enduring the disrespect of management. In the words of NFL Players Association executive director DeMaurice Smith, he was the first football player to walk away on his own terms. To walk instead of limp. He was the first black athlete to be bigger than the league itself. When players from LeBron James to Peyton Manning to Michael Jordan have leveraged their own stardom to assert their will on the direction of their teams and their leagues, it all traces back to Jim Brown.

If that is where Jim Browns story ended, it would be enough for its own book. But the mans football life was just the opening salvo to a much more sprawling epic. Brown parlayed his athletic fame into Hollywood stardom, where it was thought that he could become the black John Wayne. When this path was stymied less by his own acting ability than by the racialized rules of Hollywood, he was the first black actor to try to rewrite the script by launching his own big-time production company to make black films for a mass audience (in partnership with Richard Pryor, before they had a falling-out for the ages). He was an outspoken Black Power icon in the 1960s and spearheaded a network of Black Economic Unions to build independent hamlets of financial strength in the black community. His decades of work as a truce negotiator with street gangs are why Brown, along with Muhammad Ali and Bill Russell, is considered part of the holy trinity of socially conscious athletes.