ALSO BY WIL HAYGOOD

Tigerland: 19681969: A City Divided, a Nation Torn Apart, and a Magical Season of Healing

Showdown: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court Nomination That Changed America

The Butler: A Witness to History

Sweet Thunder: The Life and Times of Sugar Ray Robinson

In Black and White: The Life of Sammy Davis, Jr.

The Haygoods of Columbus: A Family Memoir

King of the Cats: The Life and Times of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.

Two on the River (photography by Stan Grossfeld)

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2021 by Wil Haygood

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Haygood, Wil, author.

Title: Colorization : one hundred years of Black films in a white world / Wil Haygood.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2021. | This is a Borzoi Book Published by Alfred A. Knopf. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020056224 | ISBN 9780525656876 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525656883 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: African Americans in motion pictures. | Race in motion pictures. | Racism in motion pictures. | Motion picturesUnited StatesHistory. | United StatesRace relations.

Classification: LCC PN1995.9.N4 H39 2021 | DDC 791.43/652996073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020056224

Ebook ISBN9780525656883

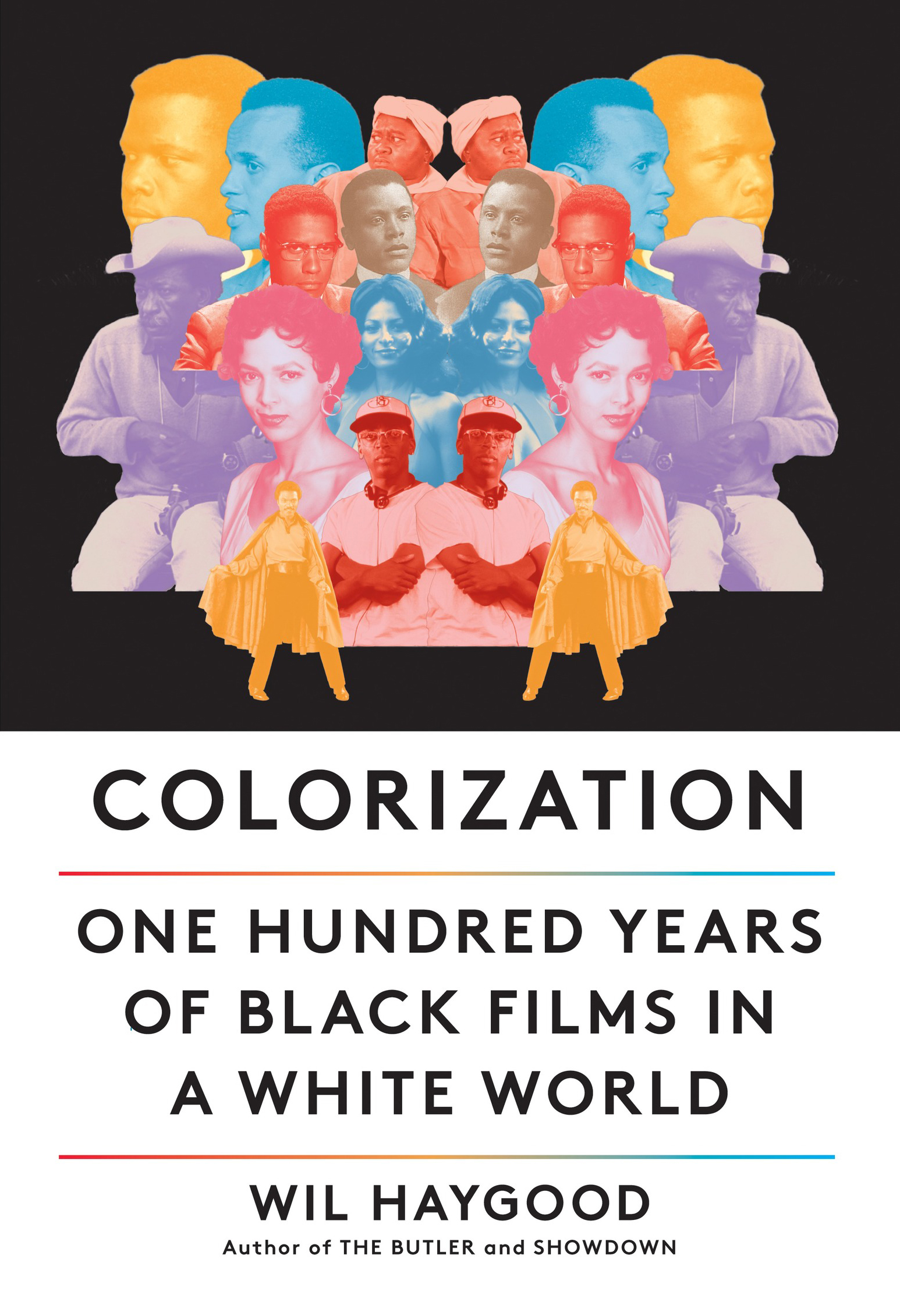

Cover images: Gordon Parks. AP/Shutterstock; Oscar Micheaux. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, NYPL; Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte. NARA; all the rest courtesy of Photofest

Cover design by John Gall

ep_prh_5.8.0_c0_r0

For Pamela Oas Williams, who loves movies

Contents

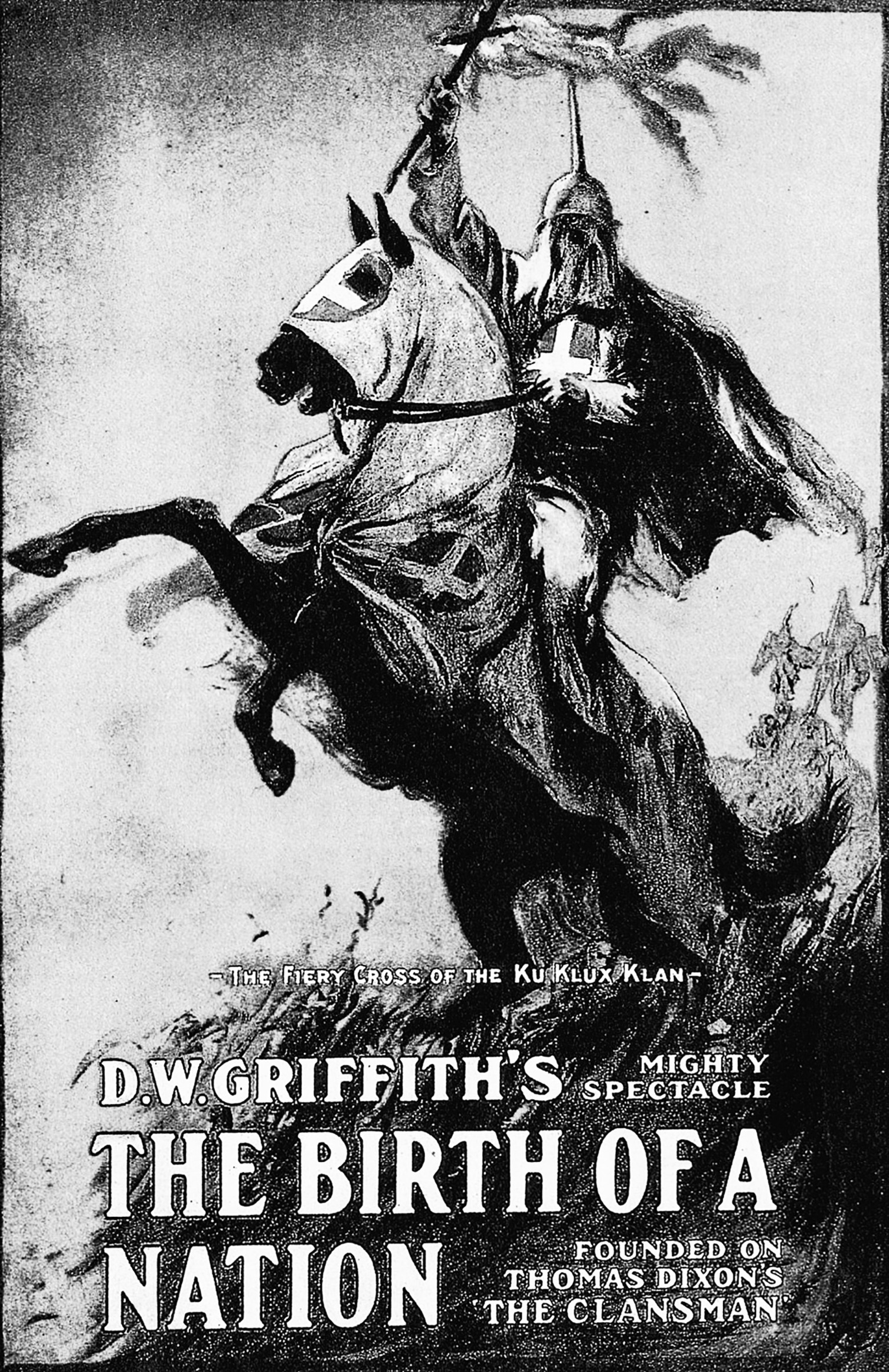

The Birth of a Nation (1915). The movie that started it all.

1

Movie Night at Woodrow Wilsons White House

I n the aftermath of the Civil War, fathers throughout the Southern statesits landscape in ruins, the populace grievinghad to start imagining a future for their sons, who had either fought in the war or grown up around it. The Lost Cause of the Confederacy left the entire region in a state of near-shock. For families that still had money from cotton and plantation revenues, a college education for their sons was seen as a key to reclaiming a bright family future. No matter how smart the women in families were, or how intellectually gifted, it remained a patriarchal-led society.

Before the war, many moneyed families became attracted to colleges and universities in the North. Princeton University was a school that particularly stood out among Southern gentry. Fifteen Southern governors could count themselves as Princeton grads. It was not lost on Southerners that Alexander Boteler, Princeton Class of 1835, had helped design the Confederate flag. Boteler was revered throughout the South. In 1857, Rev. George ArmstrongPrinceton Class of 1832published The Christian Doctrine of Slavery. He argued that Southerners took better care of slaves than Northerners could imagine, though allowing, as he put it, for some deprivation of personal liberty. Two years after Armstrongs screed, in 1859, a contingent of Princeton students from below the Mason-Dixon Line marched across their campus burning effigies of pro-Union Northern political figures. Alexander Stephens, who would serve as vice-president of the Confederacy from 1861 to 1865, proclaimed Princeton graduates to be superior to those of any other school or college in the country. During the long and bloody Civil War, seven Confederate brigadier generals were Princeton men. Some saw fit to sing the Princeton fight song as they galloped in the direction of Union cannon fire.

Joseph Wilson prided himself on his Southern ministry. In his reading of the Bible, slavery was simply a necessity. He and his wife, Jessie, had moved around the South, from Virginia to South Carolina and on to North Carolina. Jessie Wilson tended wounded Confederate soldiers. In the aftermath of wars end, the Wilson family held on to endless grudges. They were especially pained with the onset of the Reconstruction era, when the United States tried to bring a measure of equality and opportunity to formerly enslaved Blacks. Their son Woodrow Wilson was born in Virginia and grew up in and around the South amid Reconstruction. Young Woodrow thought of Reconstruction as a terrible experience for his family and other Southern whites. His earliest school tutoring came from Confederate veterans; they were men he came to admire greatly, men who told him of the great battles they had fought to keep the South firmly in the grip of whites and away from Abe Lincoln, whom they called a madman, and whose assassination they did not bemoan. In 1875, Woodrow Wilsons parentsafter he had spent a year at Davidson Collegesent him off to a school they had heard a lot about because of its Southern pedigree: the College of New Jersey, the school that would become Princeton University.

Woodrow Wilson easily took to college life. He joined clubs and organizations. He honed a gift as a public speaker; his articles for the student newspaper were widely and favorably commented upon. Professors praised his serious approach to academic life. Wilson made friends with classmates who hailed from Southern states, all bonding together over their history and hometowns. One of the people Wilson would have come across on campus was a gentleman by the name of Jimmy Johnson. Johnson began work at the school as a janitor in the 1840s and would remain there for sixty years, later also selling snacks at a makeshift stand on campus. Jimmy Johnson was a runaway slave from Maryland. He was ever mindful of trips that ranged too far from campus, nervous about bounty hunters and slave catchers. The runaway slave never met any Black students at Princeton, because they were not allowed.

While on campus, Woodrow Wilson convinced himself he might prefer a career in law. He applied to the University of Virginia Law School and was accepted. Several years later, after undergoing an abbreviated law-school stint and passing the bar exam, Wilson was settled in Atlanta and practicing law. But he felt his chosen profession boring and began imagining instead a career in public service or academia. To make that happen, he was advised to seek a doctoral degree. He applied and was accepted to Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore. He arrived on the campus in 1883.

A restless sort, Wilson sat through doctoral classes and concluded they were stuffy, and the professors too concerned with minutiae. The books assigned to him made him roll his eyes. So he began thinking of a book he himself would like to write. He began compiling notes about the inner workings of the United States government, and managed to get his book,