WHITE ROBES

SILVER SCREENS

WHITE ROBES

SILVER SCREENS

MOVIES AND THE

MAKING OF THE

KU KLUX KLAN

TOM RICE

This book is a publication of

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2015 by Tom Rice

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rice, Tom.

White robes, silver screens : movies and the making of the Ku Klux Klan / Tom Rice.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-253-01843-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-253-01836-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-253-01848-9 (ebook) 1. Ku Klux Klan (1915- ) In motion pictures. 2. Ku Klux Klan (1915 ) History. 3. Motion picture industry Political aspects United States History 20th century. 4. Motion pictures in propaganda United States History 20th century. 5. Birth of a nation (Motion picture) Influence. I. Title.

PN1995.9.K75R53 2015

791.43'655 dc23

2015017063

1 2 3 4 5 20 19 18 17 16 15

Contents

Acknowledgments

I AM WELL AWARE THAT MOST PEOPLE WHO READ ACKNOWLedgments do so in the hope of finding their own names. I must therefore begin with an apology to those missing from these pages. What follows is certainly not an exhaustive list of those deserving thanks, and I am extremely grateful to everyone who has offered me support, suggestions, and distractions during the writing of this book.

The project began many years ago while I was studying at the University of Southampton, and would not have progressed beyond an initial idea without the inspiring teaching of Mike Hammond and John Old-field. Since then I have been extremely fortunate to work more closely with Lee Grieveson, who has had an enormous influence on my work. Over the last decade, Lee has been a constant source of support, reading every page, challenging every idea, and answering every question. Occasionally he has done so without complaint. Writing any book and perhaps more so one that takes as its subject the Ku Klux Klan can be a lonely experience, but Lee has provided sage advice and friendship throughout, for which I am enormously grateful.

The manuscript has benefitted from the many other readers who have offered suggestions, in particular Mike Allen, Melvyn Stokes, and Brian Jacobson. I am especially grateful to Greg Waller, who read two versions of the manuscript and whose constructive feedback greatly shaped the final work. I was very fortunate to conduct my doctoral study at Kings College London and University College London, and I have completed this work in the company of supportive and generous colleagues at the University of St. Andrews. It seems churlish not to thank them all, but for more direct assistance, I am grateful to Robert Burgoyne, Dina Iordanova, Katherine Hawley, Leshu Torchin, David Martin-Jones, Mike Arrowsmith, Karen Drysdale, Bregt Lameris, and especially Josh Yumibe. Among the many others who have provided valuable information or material along the way are Jason Lantzer, Kevin Brownlow, and Thomas R. Pegram.

There are inevitable challenges in researching American history while based in the UK, and I am particularly indebted to the many archivists who have given so much of their time and expertise in responding to my many requests. Of the institutions that I visited, I would like to thank archivists and librarians at the University of North Carolina; the New York Public Library; the Billy Rose Theatre Collection; the Library of Congress; the Indiana State Library; the Indiana Historical Society; Ohio State University; the Ohio Historical Society; the British Library; and the British Film Institute. Many others have responded to my requests from the UK, and I am extremely pleased to acknowledge and thank, in no particular order, Boise State University (ID) (Alan Virta); the New Haven Public Library (CT) (Allison Botelho); the Hamilton East Public Library (IN) (Nancy Massey); the New Jersey State Library (Robert Heym); the New Jersey Historical Society; the Historical Society of Delaware; the Monmouth County Historical Association (NJ); the Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (Barbara Hall); the Shreve Memorial Library (LA); Kent State University (OH); the Oklahoma Historical Society; the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum (OK) (Ian Swart); the George Eastman House (Nancy Kauffman); the Warner Bros. Archives of the University of Southern California (Jennifer Prindeville); the Charlie Chaplin Archive, Cineteca di Bologna (Cecilia Cenciarelli); the Georgia State University Library (Sarah King Steiner); and the American Legion Library (Joseph J. Hovish). I have also benefitted from the emergence of online archival resources over the past decade, and would like to acknowledge, in particular, the Media History Digital Library and Newspaper Archive.

I would also like to thank everyone at Indiana University Press for their expertise and direction in developing the manuscript and bringing it to print. I am especially grateful to Raina Polivka, Jenna Whittaker, David Miller, and Eric Schramm, and to Kay Banning for her work on the index. I have also been very fortunate to receive financial support throughout my research, in particular from the Arts and Humanities Research Council. This work would not have been possible without their assistance.

Finally, I would like to thank my friends and family for providing distractions, support, and perspective, and for sitting next to me even when I insisted on reading Klan histories on public transport. I owe an enormous debt to my parents, to my brother and sister, and to Richard and Mary Bipps. I would also like to thank Caryl and John and my two inspirational grandmothers.

Above all, this book is for Suzie, Lottie, and Ernest.

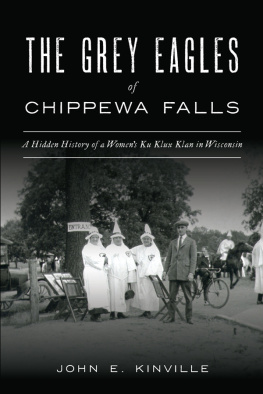

0.1. Advertisement for Knights of the Ku Klux Klan and The Birth of a Nation, Atlanta Journal, 9 December 1915.

Preface

ON MONDAY, 6 DECEMBER 1915, THE NIGHT OF THE ATLANTA premiere of The Birth of a Nation, the recently formed Ku Klux Klan, mounted and on foot, paraded down Peachtree Street and fired rifle salutes in front of the theatre. Ten months earlier, at the films national premiere at Clunes auditorium in Los Angeles, actors in full Ku Klux Klan regalia had sat on horseback outside the theater, re-creating the on-screen image. Much had changed between these two dates, however. In Los Angeles, which was fast becoming the center for film production, theatrical Klansmen were there to provide publicity for the film. In Atlanta, a city increasingly riven by Jim Crow segregation and by national reports of mob violence, active Klansmen now used the film to introduce and publicize a new group that was emerging at the exact moment of the films local release.

Next page