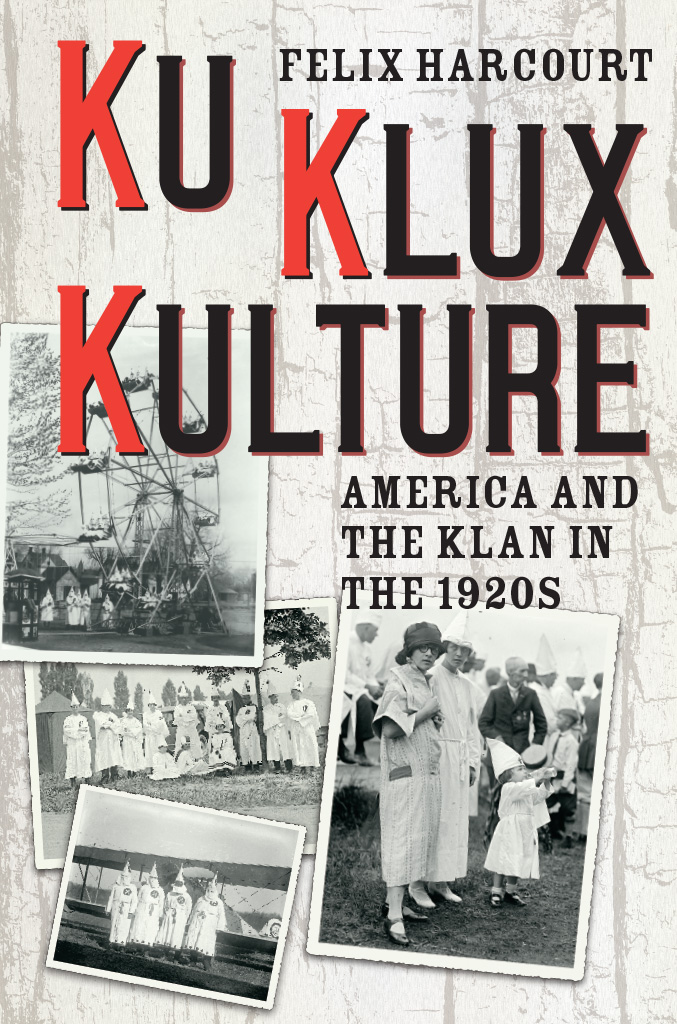

Ku Klux Kulture

America and the Klan in the 1920s

Felix Harcourt

The University of Chicago Press

CHICAGO & LONDON

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2017 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-37615-8 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-37629-5 (e-book)

DOI : 10.7208/chicago/[9780226376295].001.0001

A portion of the material printed in this book appeared previously in the article Invisible Umpires: The Ku Klux Klan and Baseball in the 1920s, in NINE: A Journal of Baseball History & Culture 23, no. 1, 2015, by Felix Harcourt and published by the University of Nebraska Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Harcourt, Felix, author.

Title: Ku Klux kulture : America and the Klan in the 1920s / Felix Harcourt.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017007718 | ISBN 9780226376158 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226376295 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH : Ku Klux Klan (1915)History. | United StatesEthnic relations. | Popular cultureUnited States20th century. | RacismUnited States.

Classification: LCC HS 2330.K63 H37 2017 | DDC 322.4/2097309042dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007718

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

Ordinary Human Interests

There is really no better reason for outsiders to regard Klansfolk as strange, other-worldly creaturesincapable of ordinary human interests, including clambakesthan there is for Klansfolk to think that way about outsiders.

CHARLES MERZ, The Independent, February 12, 1927

If it requires acceptance of the ideas of this committee to remain immune from the brand of un-Americanism, Maltz asked, then who is ultimately safe from this committee except members of the Ku Klux Klan? Like his fellow witnesses, the writer was cited for contempt by the committee. Maltz would be blacklisted as part of the Hollywood Ten and would not receive another screen credit until 1970. Nonetheless, he declared he would not be dictated to or intimidated by men to whom the Ku Klux Klan, as a matter of committee record, is an acceptable American institution.

Maltz had likely discussed this piece of political theater with the so-called Dean of the Hollywood Ten, John Howard Lawson, who had been cited by the committee the day before as the first of the unfriendly witnesses. J. Parnell Thomas had refused to allow the screenwriter to read a prepared statement that accused Thomas of being a petty politician serving forces trying to introduce fascism. Lawson had then answered questions about

Twenty-two years earlier, Lawson had offered a similar argument about the threat of repressive forces in a play that the Chicago Tribune described as wild and weird beyond the dreams of the most visionary of the radicals. It was also a play that offered a very different theatrical take on the Klan from that of Maltzs statement. Lawsons experimental 1925 jazz symphony of modern life, Processional, depicted the Ku Klux Klan deeply embedded in the firmament of contemporary societyas an American institution. Indeed, the plays third act climaxed with what one theatergoer called the Ballet of the Ku Klux Klan.

Nor was Lawson the only one to present audiences of the 1920s with the spectacle of dancing Klan members. The touring stage production The Awakening drew audiences with a garish amalgam of mawkish melodrama (lifting the plot from The Birth of a Nation) and cabaret showgirls. One musical number in the show, Daddy Swiped Our Last Clean Sheet and Joined the Ku Klux Klan, was a particular hit. Copies of the song could be purchased as sheet music, a piano roll, or a phonograph record. Cultural consumers in the 1920s could not only see the Klan on stage and hear about the organization in popular song, but also listen to the Klan on radio. They could read about the organizations exploits in newspapersor buy the organizations own periodicals. They could watch the group battle it out on the baseball field. They could thrill to the adventures of the Klan in novels and on movie screens. The Awakening was seen by more than ten times as many people as bought F. Scott Fitzgeralds The Great Gatsby in the 1920s. Yet these Klannish cultural artifacts have been all but forgotten, along with their significance.

As the standard narrative goes, the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan were reborn on November 25, 1915, with a cross burning at Stone Mountain, Georgia. The architect and Imperial Wizard of this revival was William Joseph Simmons, a former circuit-riding preacher and professional fraternal organizer. Combining elements of the original Reconstruction-era Klan with romanticized ideas lifted from the box-office smash of the year, The Birth of a Nation, Simmons hoped to create the ultimate Southern fraternal organization. The lynching of local Jewish businessman Leo Frank for the murder of employee Mary Phagan, and the ensuing calls for a revived Klan to enforce a new home rule, provided impetus for the Imperial Wizards efforts.

The self-proclaimed Invisible Empire began to expand rapidly, accompanied by a series of violent incidents involving masked Klansmen. The organizations growing popularity, though, seemed limited to the South. The September 1921 New York World expos of the Klan changed that completely. The series sparked a congressional investigation, earned the World a Pulitzer Prize, and is remembered as one of the most celebrated pieces of American twentieth-century journalism. It also rocketed the Ku Klux Klan to national prominence.

For three weeks, the Klan dominated the front page of a major New York daily and affiliates around the country. With the help of disillusioned ex-Kleagle Henry P. Fry, the newspaper concentrated on revealing as many of the organizations secrets as possible: listing violent crimes attributed to Klansmen; naming more than two hundred Kleagles nationwide; reprinting Klan advertisements, recruiting letters, and a questionnaire to determine the eligibility of prospective members; and divulging the contents of the Klans Kloran, or book of ceremonies, including the organizations oaths and rituals, the meaning of their titles and code words, and even a diagram of their secret handshake. These revelations were accompanied by sensationalistic denunciations of the grotesque organization.

By the end of the series on September 26, the World was convinced that it had given Kluxism a death blow. By hounding them for statements on the story, the paper had forced the majority of New Yorks officials into publicly declaring their opposition to the Klan. Little more than two weeks after the

Far from a death blow, though, the appearance of the Klan in the New York World and its affiliates meant that word of the organizations rebirth was transmitted nationally far more effectively than Klan members would ever have been able to achieve themselves. Even as the newspaper coverage sparked a wave of condemnation, it also saw the beginning of a surge of support for the Invisible Empire. Some readers allegedly even attempted to join the reborn Klan using blank application forms that the

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).