For my wife, daughters and mother. Thank you for your patience and the gift of curiosity.

Contents

Preface7

PART I9

Chapter 1: Movie Night11

Chapter 2: The Klan Comes to Canada29

Chapter 3: Klan Rising (1925)53

Chapter 4: Year of the Klan (1926)75

Chapter 5: The Canadian Knights (192627)94

Chapter 6: Moose Jaw Moment116

Chapter 7: Getting Out the Vote (1928)133

Chapter 8: Ontario Burning (192930)151

Chapter 9: Wild Rose Country: The Klan in Alberta, 1930s157

Chapter 10: Waiting for Hitler (193039)175

PART II185

Chapter 11: Klan Redux187

Chapter 12: Goat Worshippers203

Chapter 13: Island in the Sun219

Chapter 14: To Tripoli and Beyond, the 1980s

and Early 1990s235

Chapter 15: Le Klan in Quebec, 1990s251

Chapter 16: Klan Online in the 2000s265

Acknowledgements279

Endnotes280

Index309

Preface

PREFACE

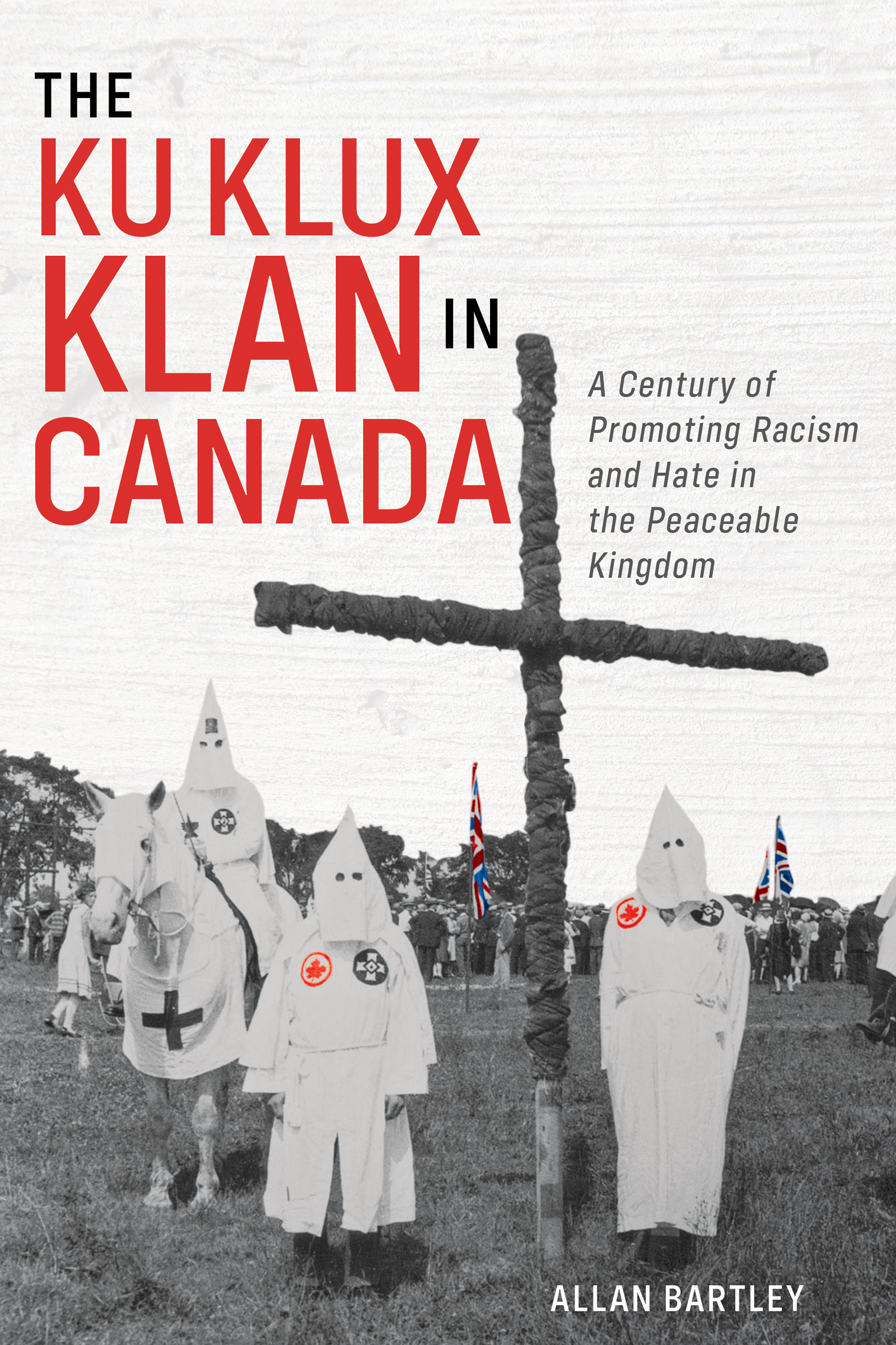

Hate has a name. Hate has a face. Hate has an address. It lives in Canada. The Ku Klux Klans more than one-hundred-year presence in Canada demonstrates how hate lived and flourished and still endures in the nation sometimes known as the Peaceable Kingdom. Our neighbours were partly to blame, but Canadians can also blame themselves.

Because we believe that it cant happen here, we are too hesitant to talk about the way in which some people and politicians are already admiring the reflection they see when they look south, novelist Alexi Zentner wrote in the Globe and Mail in the summer of 2019. We think of virulent hatred as a thing that comes from the history books. And yet, the history books are coming to life again.

The challenges of writing a book on the history of the Ku Klux Klan in Canada go beyond creating a narrative. There is the concern that to write about hate is to condone it. To write about the leaders and their followers runs the risk of glorifying them or ridiculing them or magnifying or minimizing their ideas and impact. The odious reality of the Ku Klux Klan and its imitators over the decades speaks for itself. We need to confront that reality.

The book examines motivations for both leaders and followers. For many leaders, the Ku Klux Klan was a money-making enterprise. For many members, the organization provided a platform to express hate and resentments they would not express as individuals. For some, it offered a chance to be the centre of attention a moment of recognition that they could parlay into something better for themselves. For others, it allowed them to commit acts of brutality that they would not have engaged in on their own. For victims of the fear, threats, slights, intimidation, beatings and more, the Ku Klux Klan was and is the face of hatred.

This narrative seeks to capture the flow of history; it does not detail all the realities stemming from hate over a century. The Ku Klux Klan will endure as an idea in Canada so long as any stunted human spirit can scrawl KKK on a wall and walk away with impunity. In the course of history, and in moments like ours, these degradations of humanity live again and thrive under many different guises. But Canadian society has a better chance than many of lifting human spirits beyond crude expressions and acts of hate if we expose and beat back the organizations and groups and individuals who promote such ideas when they appear.

Hate has a name, a face and an address. We need to know these things so that we can confront hate wherever it lives in the Peaceable Kingdom or elsewhere. From there we move forward.

. Alexi Zentner, Im a Canadian Living in the U.S. Whats Happening There Could Happen Here Too, Globe and Mail, July 4, 2019.

Part I

Chapter 1

MOVIE NIGHT

The Gayety Burlesque on Yonge Street offered the Sporting Widows Ladies Band to entertain Toronto audiences in September 1915. Up the street, Loews Theatre featured high-class vaudeville acts starring the McDonald Trio, Jack Taylor, Hallan & Hayes, Cook & Stevens and more. The Hippodrome at City Hall Square had three shows daily with unique and complete photo-plays and feature film attractions. But over at the prestige-laden Royal Alexandra Theatre on King Street, something completely different was on offer. The display ads blared:

Eighth Wonder of the World, Took 8 Months to Produce. 18,000 People. 3,000 Horses. Cost $560,000. The Basil Corporation Presents D.W. Griffiths The BIRTH of a NATION. The Most Stupendous Dramatic Spectacle the Brain of Man has yet Visioned and Revealed. Night Prices 50c to $1.50. All Matinees 50c to $1.00.

The ideas and images of the Ku Klux Klan came to Canada in September 1915 through the new medium of silent film. For the next decade, the spectacle of The Birth of A Nation nurtured an organization dedicated to white racial supremacy, the suppression of Black people, Jews, Catholics, Asians, Chinese, eastern Europeans and just about anybody who looked, sounded or seemed different from the white Protestant majority in Canada and the United States. The trend continued throughout the century that followed, with exploitation of new media of all kinds (film, radio, television, Internet) coming to define how hate was projected, narrated, organized and delivered by the Ku Klux Klan an organization foreign to Canada but one that found fertile soil to take root.

But in 1915, only a year into the national trauma of the First World War, with its slaughter and sorrows, apprehensive Canadians welcomed the diversion offered by the new moving picture coming out of the United States. The Birth of A Nation opened in theatres across the country that fall, drawing crowds everywhere. And everywhere the advertising meticulously prepared by Hollywood publicity teams lauded the Eighth Wonder of the World.

The reception at the Royal Alexandra in Toronto was repeated at Vancouvers Main Street Avenue Theatre and Montreals theatres during that looming fall of 1915. Crowds lined up around the block to buy tickets. There were continuous showings for weeks on end. The films artistic and technical innovations animated discussions in the street and filled columns of newsprint.

The features of the first part are the battle scenes, especially that showing the dash of the Confederate troops for the trenches of the Federals, which might suggest the trench warfare in Flanders during the present war, critic Edwin Parkhurst wrote in the Globe the day after the film opened in Toronto.

White Canadians in particular couldnt get enough of the story depicting the aftermath of the Confederate states defeat. The United States Civil War continued to be a living presence a half-century after the conflict that killed more than six hundred thousand Americans and devastated the life and economy of the southern states. Reunions of American Civil War veterans, including those from the Confederacy, were regularly reported in the Canadian media, particularly around the fiftieth anniversary of the wars end in 1915. The Confederacy had had many Canadian supporters in the 1860s, and their children and grandchildren flocked to see The Birth of A Nation.

In Toronto, local police magistrate Colonel George Denison, never shy about seeking publicity for his life and adventures, attended the 1916 reunion of the United Confederate Veterans association in Birmingham, Alabama. The Globe newspaper was happy to provide a platform for his southern travels.