Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

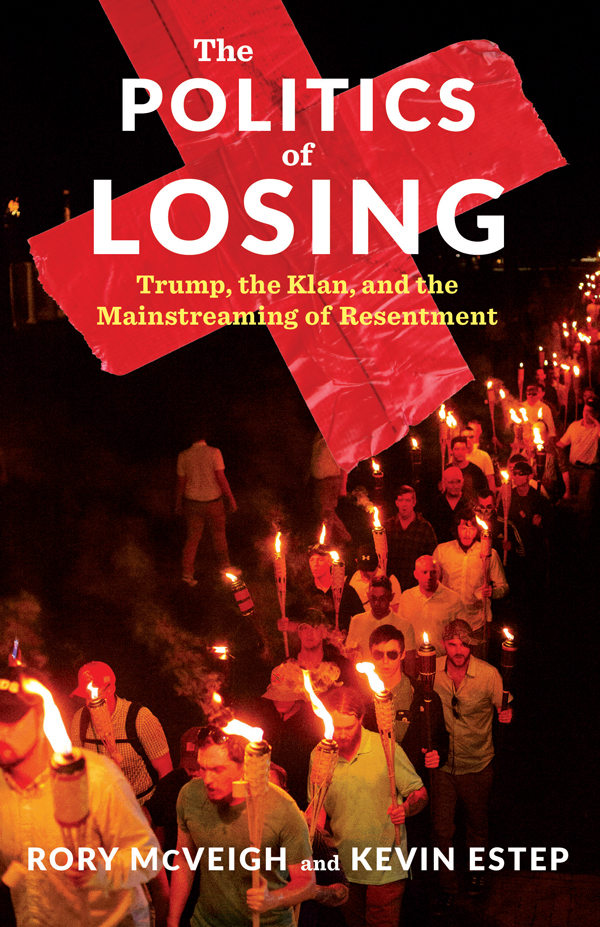

THE POLITICS OF LOSING

THE POLITICS OF LOSING

Trump, the Klan, and the Mainstreaming of Resentment

RORY MCVEIGH AND KEVIN ESTEP

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2019 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54870-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: McVeigh, Rory, author. | Estep, Kevin, author.

Title: The politics of losing : Trump, the Klan, and the mainstreaming of resentment / Rory McVeigh and Kevin Estep.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018048997 (print) | LCCN 2018056015 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231190060 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: White nationalismUnited StatesHistory. | White supremacy movementsUnited StatesHistory. | Ku Klux Klan (1915-)History. | WhitesRace identityUnited StatesHistory. | United StatesRace relationsPolitical aspects. | Trump, Donald, 1946 | United StatesPolitics and government2017

Classification: LCC E184.A1 (ebook) | LCC E184.A1 M356 2019 (print) | DDC 320.56/909dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018048997

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Noah Arlow

Ignorant, superstitious, and filthy Mexicans are scattering far and wide throughout the country, taking the place of American laborers. They are reported as far north as the sugar beet fields of Michigan, where they are ousting white families, and thousands are settling in the southwest. Our immigration laws are still far too lax. Something should be done, and speedily, to curb this evil.

Imperial Night-Hawk , the newspaper of the Ku Klux Klan, May 30, 1923

CONTENTS

O n a hot July day in central Indianathe kind of day when the heat shimmers off the tall green corn and even the bobwhites seek shade in the brusha great crowd of people clustered around an open meadow. They were waiting for something. Their faces were expectant, and their eyes searched the bright blue sky.

Suddenly, they began to cheer. They had seen it: a speck that came from the south and soon grew into an airplane. As it came closer, it glistened in the sunlight, and they could see that it was gilded all over. It circled the field slowly and seesawed in for a bumpy landing. Soon a man emerged, to a new surge of applause, and a small delegation of dignitaries filed out to the airplane to meet him. With the newcomer in the lead, the column recrossed the field, proceeded along a lane carved through the multitude, and reached a platform decked with flags and bunting. He mounted the steps, walked forward to the rostrum, and held up his hand to hush the excited crowd.

This is the account, almost word for word, of a journalist named Robert Coughlan on the Fourth of July, 1923. This was a Klan rallyarguably the largest in historya tristate Konklave that brought members from Ohio and Illinois to gather together in Kokomo, Indiana. Some reports place the attendance at one hundred thousand. For Coughlan, who had been born and raised Catholic in Kokomo, there was special reason to remember the Ku Klux Klan.

The man at the rostrum was David C. Stephenson, though he went by D. C. Once a lowly Indiana coal dealer, on that day he was installed to the exalted position of Grand Dragon, granting him control over the thriving northern realm of the Klan. With millions of faithful members, he had gained tremendous political power. But before that day would come, he would first build a political machine headquartered in Indiana.

Coughlan continues: The Grand Dragon paused, inviting the cheers that thundered around him. Then he launched into a speech. He urged his audience to fight for one-hundred-percent Americanism and to thwart foreign elements that he said were trying to control the country. He spoke about how our once great nation had veered from the course charted by her founders, and he railed against political corruption, a rigged electoral system, and the undemocratic power of the Supreme Court to nullify the will of the people. Every official who violates his oath to support the constitution by betrayal of the common welfare through any selfish service to himself or to others spits in the soup and in the face of democracy. He is as guilty of treason as though he were a martial enemy.

As he finished, and stepped back, a coin came spinning through the air. Someone threw another. Soon people were throwing rings, money, watch charms, anything bright and valuable. At last, when the tribute slackened, he motioned his retainers to sweep up the treasure. Then he strode off to a nearby pavilion to consult with his attendant Kleagles, Cyclopses, and Titans.

This rally was in the midst of the phenomenal rise of the Klan during the early 1920s. By 1925, Klan membership was anywhere from 2 to 5 million members, not counting the millions who supported the Klan without ever joining up.

Like the original Klan, which was created during Reconstruction in the late 1870s, and like the Klan that mobilized to thwart the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the Klan of the 1920s existed to advance and maintain white supremacy. But it also had a broader agenda, and it stunned contemporary observers as it attracted millions of followers and grew particularly strong outside of the former Confederacy, in states like Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Indiana.

The Klans national leader, Imperial Wizard Hiram Wesley Evans, was also there the day of Stephensons speech, introducing him with a ringing message of optimism and good cheer. A week later, Evans gave a speech at Buckeye Lake in Ohio, musing on the origins of this second coming of the Klan.

Among the students of the old Reconstruction, he said, there was an itinerant Methodist preacher who, living in the atmosphere and under the shade of the former greatness of the Klan, dreamed by day and night of a reincarnation of the organization which had saved white civilization to a large portion of our country. This preacher was Colonel William Joseph Simmons, who had refounded the Klan outside Atlanta, Georgia, in 1915. Slowly, under the dreamings of a wondering mind, the Klan took some hazy kind of form. As this man wandered in the streets of the Southern city in which he lived, preaching the doctrine of a new Klan in his emotional manner, there slowly came to the standard men of dependable character and sterling worth, who were able to lend some kind of concrete form to the God-given idea destined to again save a white mans civilization.

Evanss tribute to Simmons winked at the Klans slow growth and aimlessness in the years following its rebirth. By the early 1920s, however, a new leadership had hit upon a formula for rapid expansion. Simmons had hired two publicists, Edward Young Clarke and Elizabeth Tyler, who enlisted a team of recruiters they called Kleagles. The Kleagles traveled the country, forging close ties with fraternal lodges and Protestant congregations to attract members and money. As they ventured beyond the South, they discovered deep pockets of discontent among white Americans. Clarke and Tyler decided that this discontent could be harnessed into a fearsome political movement. They instructed Kleagles to promise new members that only a powerful one-hundred-percent American organization such as theirs could save them.