Copyright 2021 by The University of Arkansas Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book should be used or reproduced in any manner without prior permission in writing from the University of Arkansas Press or as expressly permitted by law.

ISBN: 978-1-68226-159-0

eISBN: 978-1-61075-737-9

Manufactured in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 5 4 3 2 1

Designed by Liz Lester

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Barnes, Kenneth C., 1956 author.

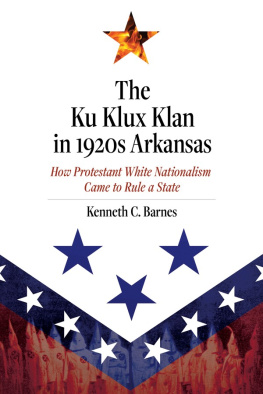

Title: The Ku Klux Klan in 1920s Arkansas: how Protestant white nationalism came to rule a state / Kenneth C. Barnes.

Description: Fayetteville: The University of Arkansas Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: This volume charts the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in 1920s Arkansas and the impact of the organizations success on the development of the stateProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020026472 (print) | LCCN 2020026473 (ebook) | ISBN 9781682261590 (cloth) | ISBN 9781610757379 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Ku Klux Klan (1915 ). Realm of ArkansasHistory.

Classification: LCC HS2330.K63 B36 2021 (print) | LCC HS2330.K63 (ebook) | DDC 322.4/20976709042dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020026472

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020026473

PREFACE

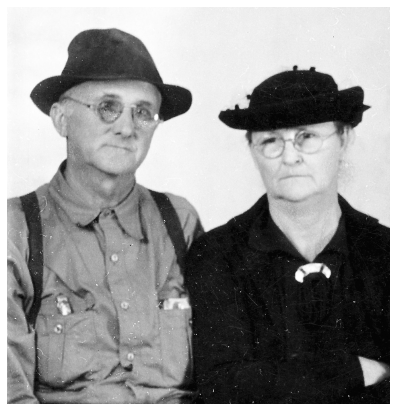

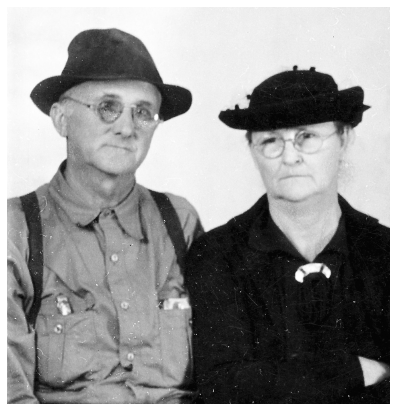

When my mother was a girl, she found her fathers Klan robe. My grandfather, William Manie Bird, explained to his curious daughter that the Klan only did good things for the community. As an example, he described an evening in which Klansmen went to the home of a habitual drunkard in the community who neglected his family. The hooded figures tied the man to a fencepost, whipped him, and threatened that if he did not lay off liquor and get a job to support his family, they would return and use stiffer measures. My grandfather would have been a part of the Morrilton Klan No. 46 in Conway County, Arkansas. Grandfather Bird owned a general store in the Birdtown community, about fifteen miles northeast of Morrilton. His conversation with my mother probably took place in the late 1920sshe was born in 1918by which time the Morrilton Klan was no more. But he still had his robe.

On March 15, 1922, just a couple of months after the organization of Klan No. 46, my mothers thirteen-year-old brother was on trial for murder at the courthouse in Morrilton. At the close of a Baptist church meeting in Birdtown on the evening of January 29, his pocket knife somehow plunged into the chest of another boy, who died of the injury two weeks later. My uncle and his family claimed that the boy stumbled on the steps of the church and fell onto my uncles knife. The family of the victim and other witnesses said it was premeditated murder, for the boys had exchanged words before the church meeting began.

In the midst of my uncles trial at the courthouse in Morrilton, just after two in the afternoon, three robed and masked Klansmen ceremoniously entered the courtroom and handed a letter to the presiding circuit judge Jackson T. Bullock. Their arrival created quite a stir. One African American spectator fell off a bench with fright, and several others commenced climbing out of the windows of the courtroom. The judge immediately sent the jury out of the room. He read aloud the Klans letter, which commended him and the grand jury for their service in maintaining law and order in the county. Then the men in white robes solemnly left the courtroom. After the crowd was quieted, the jurors returned, and the trial resumed. Around nine that evening, the jury brought Judge Bullock its verdict: voluntary manslaughter. My uncle was sentenced to two years in the state penitentiary.

My grandfather, however, had another plan. He appealed the judgment to the Arkansas Supreme Court, citing the disruption, intimidation, and fear brought on by the sudden appearance in court of the Ku Klux Klan. My uncles lawyer had raised no such objection at the trial. I wonder, of course, if the intervention of Grandpa Birds Klan brothers had been planned all along. Or perhaps my grandfather joined Klan No. 46 after the Klansmen appeared at his sons trial. In any case, my uncle never served any prison time. When the states high court considered his case the following June, it overturned the verdict and called for a new trial. On October 7, my uncle was back in circuit court in Morrilton, this time receiving a sentence of one year that was suspended, pending good behavior.

For as long as I can remember, I have known that my grandfather was a Klansman. He died before I was born, so I never knew him. My mother told me the story about finding her fathers robe sometime in the 1960s. The account of her brothers knifing another boy, however, was a family secret. She told me this story just a few years before her death in 2002, and she believed the killing was an accident. Later, while doing research for this book, I stumbled on information about my uncles trial and appearance there of the Ku Klux Klan. It was well covered in the newspapers. My mother probably did not even know this part of the story.

I hope readers will indulge this recounting of my family history. Authors, even historians, write about things that have personal meaning to them. My previous book that led me to the 1920s Klan was an attempt to understand the deeply seated prejudices my parents held toward Roman Catholics. As a child I was mildly traumatized by angry conversations about religion when my older brother, as a teenager, converted to Catholicism. In researching anti-Catholicism, I learned about how the Ku Klux Klan institutionalized and propagandized hate toward Catholics and others. I could understand how my mothers views in the 1960s came from her own childhood in the 1920s. My purpose is not to disgrace those who, like me, have connections with a shameful past, but instead to better understand ourselves and the road that brought us to the present.

The information for this study has come largely from newspapers of the 1920s. The modern reader would be surprised at how public the Klan made its activities. The KKK frequently sent letters to local newspapers, describing the organizations goals and activities. Many small-town newspapermen were members of the Invisible Empire, as the Klan called itself. Also, one should remember how many more newspapers were published then as opposed to today. The 1920s probably witnessed the greatest number and readership of newspapers in the history of the United States; radio was just beginning to pose the first great challenge. Television and the internet would continue the assault. Just as I was completing my draft of this book, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette stopped paper delivery to my town and most of the state. This daily newspaper is the successor to two Little Rock dailies, the Arkansas Democrat and the Arkansas Gazette, both major sources for this study.

My grandfather the Klansman, Manie Bird, and my grandmother, Mary Gilliam Bird.

I have benefited enormously from the digitization of the Arkansas Gazette, Arkansas Democrat

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.