Copyright 2010 by Susan Campbell Bartoletti

All rights reserved. Originally published in hardcover by Houghton Mifflin, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Bartoletti, Susan Campbell.

They called themselves the K.K.K. : the birth of an American terrorist group / by Susan Campbell Bartoletti.

p. cm.

1. Ku Klux Klan (19th cent.)Juvenile literature. 2. Ku Klux Klan (1915)Juvenile literature. 3. RacismUnited StatesHistoryJuvenile literature. 4. Hate groupsUnited StatesHistoryJuvenile literature. 5. United StatesRace relations.

I. Title.

HS2330.K63B37 2010

322.420973dc22

2009045247

ISBN: 978-0-618-44033-7 hardcover

ISBN: 978-0-544-22582-4 paperback

eISBN 978-0-547-48803-5

v1.1115

Title page photo credit: Harpers Weekly, October 24, 1874; Library of Congress

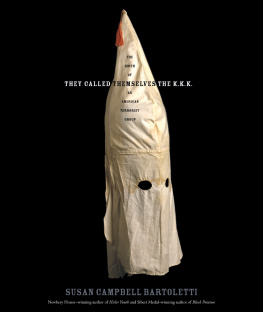

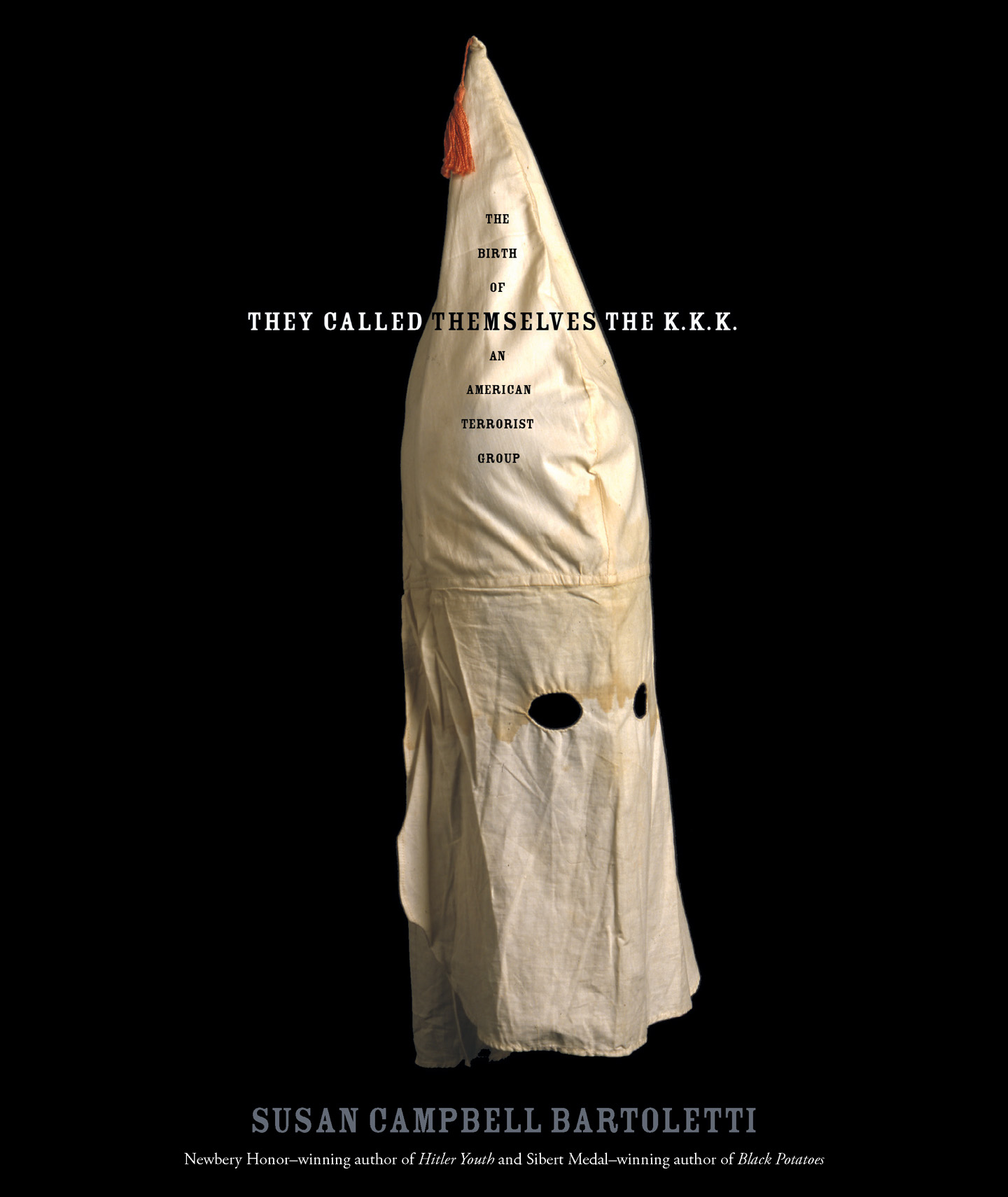

ABOUT THE COVER: Until its mysterious disappearance, the Klan hood pictured on the cover was housed in the Old Courthouse Museum in Vicksburg, Mississippi. Although it closely resembles costumes worn during the Reconstruction period, its more likely that the hood dates from the 1920s, judging by its small red tassel.

The method of force which hides itself in secrecy is a method as old as humanity. The kind of thing that men are afraid or ashamed to do openly, and by day, they accomplish secretly, masked, and at night. The method has certain advantages. It uses Fear to cast out Fear; it dares things at which open method hesitates; it may with a certain impunity attack the high and the low; it need hesitate at no outrage of maiming or murder; it shields itself in the mob mind and then throws over all a veil of darkness which becomes glamor. It attracts people who otherwise could not be reached. It harnesses the mob.

W. E. B. Du Bois, 1935

Albion Tourge, A Fools Errand, by One of the Fools: The Famous Romance of American History (New York: Fords, Howard, & Hulbert, 1879)

A Note to the Reader

In the pages of this book, you will meet people who lived during the years that followed the Civil War, a time known as Reconstruction. These people come from a variety of backgrounds. You will read the stories of the Ku Klux Klansmen and their victims from a variety of sources, including congressional testimony, interviews, and historical journals, diaries, and newspapers.

Wherever possible, I have let the people of the past speak in their own voices. Some of these people use crude language. No matter how difficult it is to see the offensive words in print, I have made no attempt to censor these historical statements.

You will see images from pictorial newspapers such as Harpers Weekly and Frank Leslies Illustrated Newspaper and other sources. These images depict people, events, and viewpoints of the time. Some of the depictions are caricatured and are racially offensive. I deeply regret any offense or hurt caused by the images, but again I have chosen not to censor.

You will also meet former slaves who were interviewed more than seventy years after the end of the Civil War. These interviews are commonly referred to as the Slave Narratives. Most of these men and women were children or young adults in their teens and early twenties when the Civil War ended, and were in their eighties and nineties when interviewed by government reporters in the late 1930s.

The government reportersmostly white men and womenwere instructed to transcribe or write the words in a way that reflected the inteviewees speech patterns. As a result, some of the dialect may be dificult to read. Even so, I have chosen not to alter the interviews or transpose the dialect into standardized English.

CHAPTER 1

Bottom Rail Top

In the spring of 1865, as rain softened the hard ground, plenty of work was found for every pair of hands on the Williams plantation in Camden, Arkansas, despite the Civil War, which was still raging at the end of its fourth year.

Field hands chopped away old withered cotton stalks to make room for this years seeds. Plow hands hitched mules to plows and furrowed the fields, turning over mile after mile of rich black dirt. Other slaves followed the plow, sowing the seeds and working manure into the furrows and building up the cotton beds.

Near the Big House, slave children worked in groups, too, stooping over vegetable garden rows, pulling weeds, plucking insects from the green shoots, harvesting the early vegetables, and readying the damp earth for the warm-season seeds.

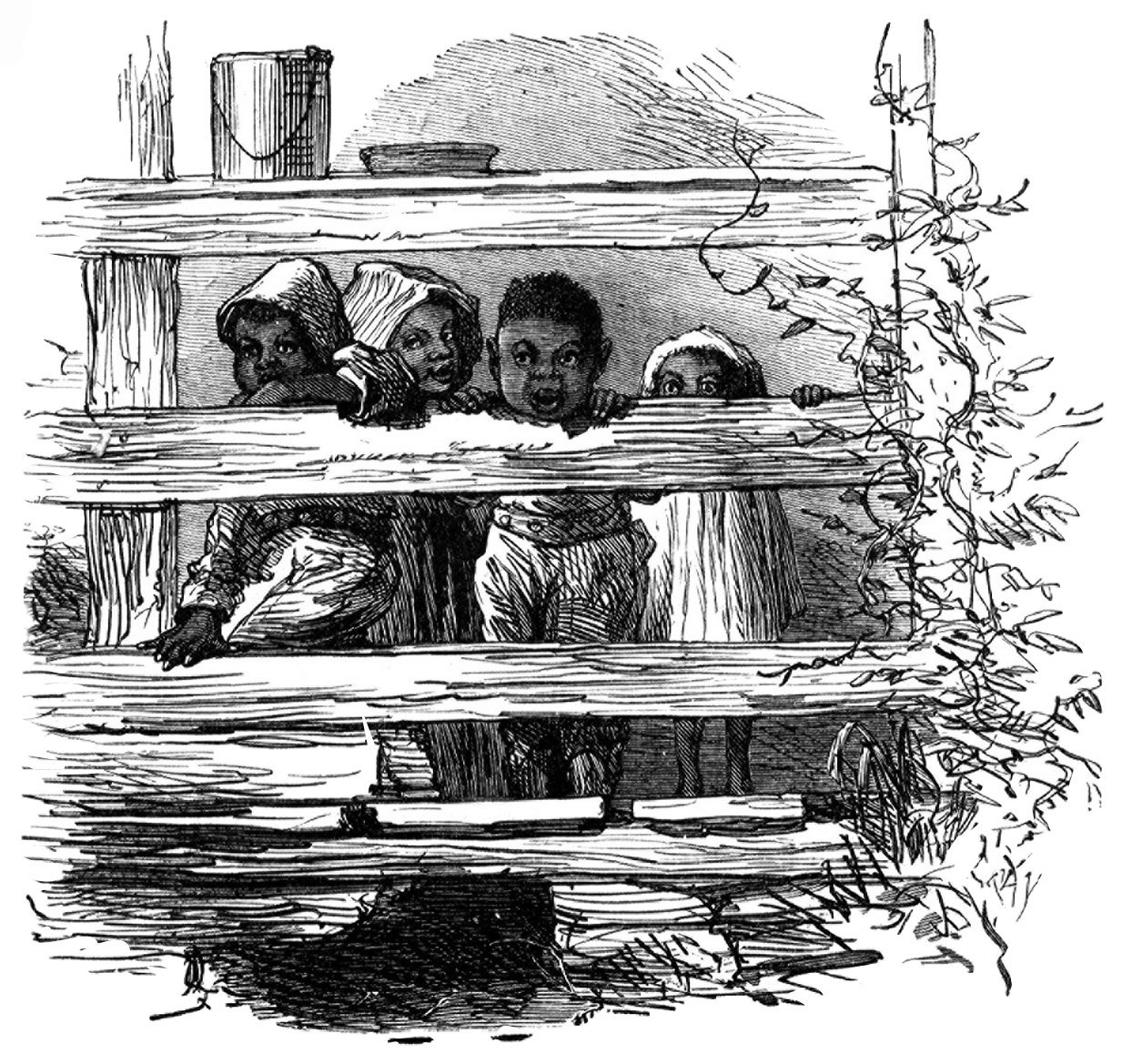

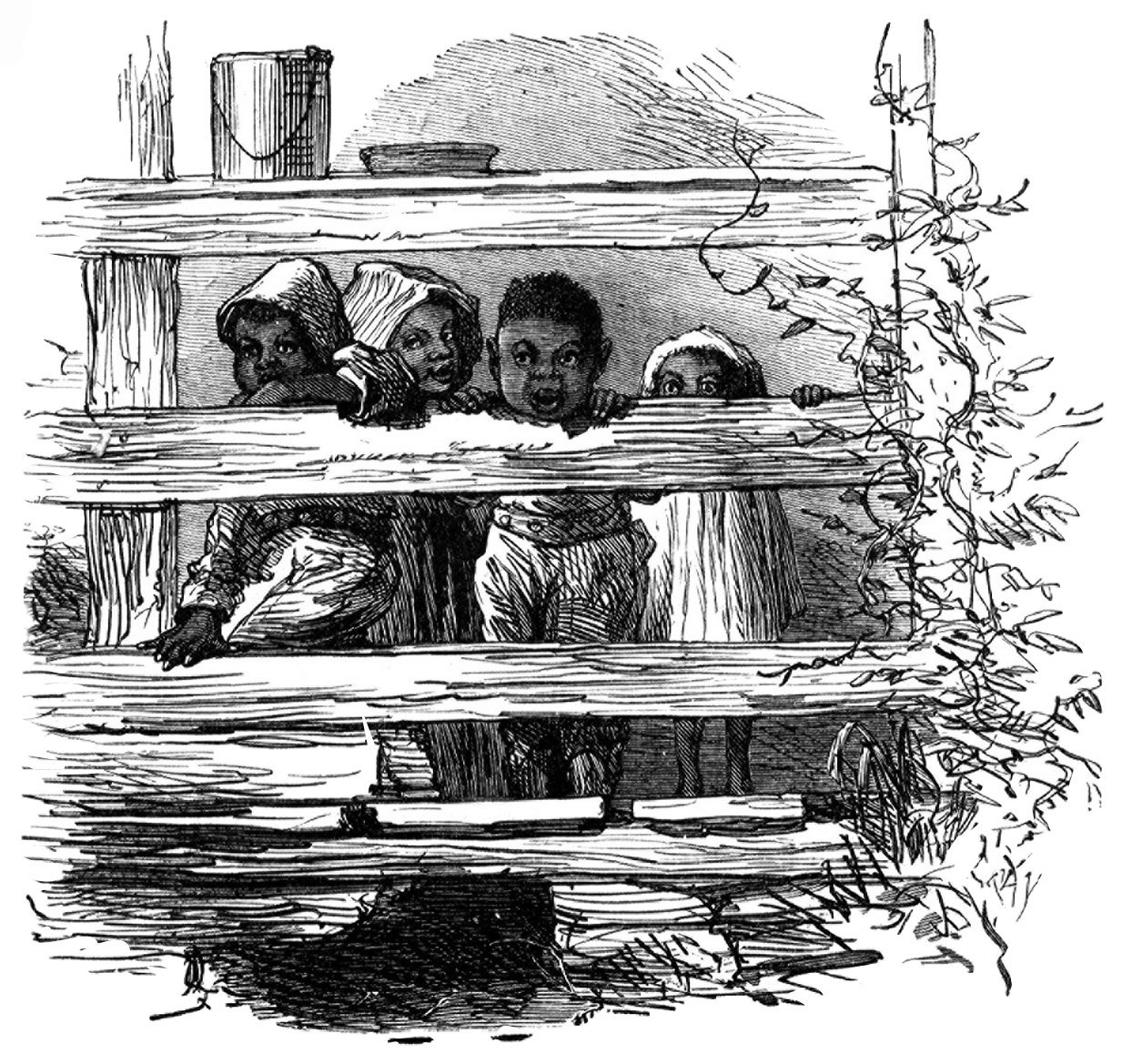

In this illustration, called The Rising Generation, children climb fence rails that represent the upper, middle, and bottom economic classes of Southern society.

Albion Winegar Tourge, The Invisible Empire

Inside the Big House, there was plenty of work, too. For fourteen-year-old Mittie Williams, who worked as a house slave, there was Miss Eliza to tend to. Ever since Old Master diedin the South, use of the word old indicated respect for the persons yearsMittie had become the elderly womans constant companion. She skeered to stay by herself, Mittie recalled seventy-two years later.

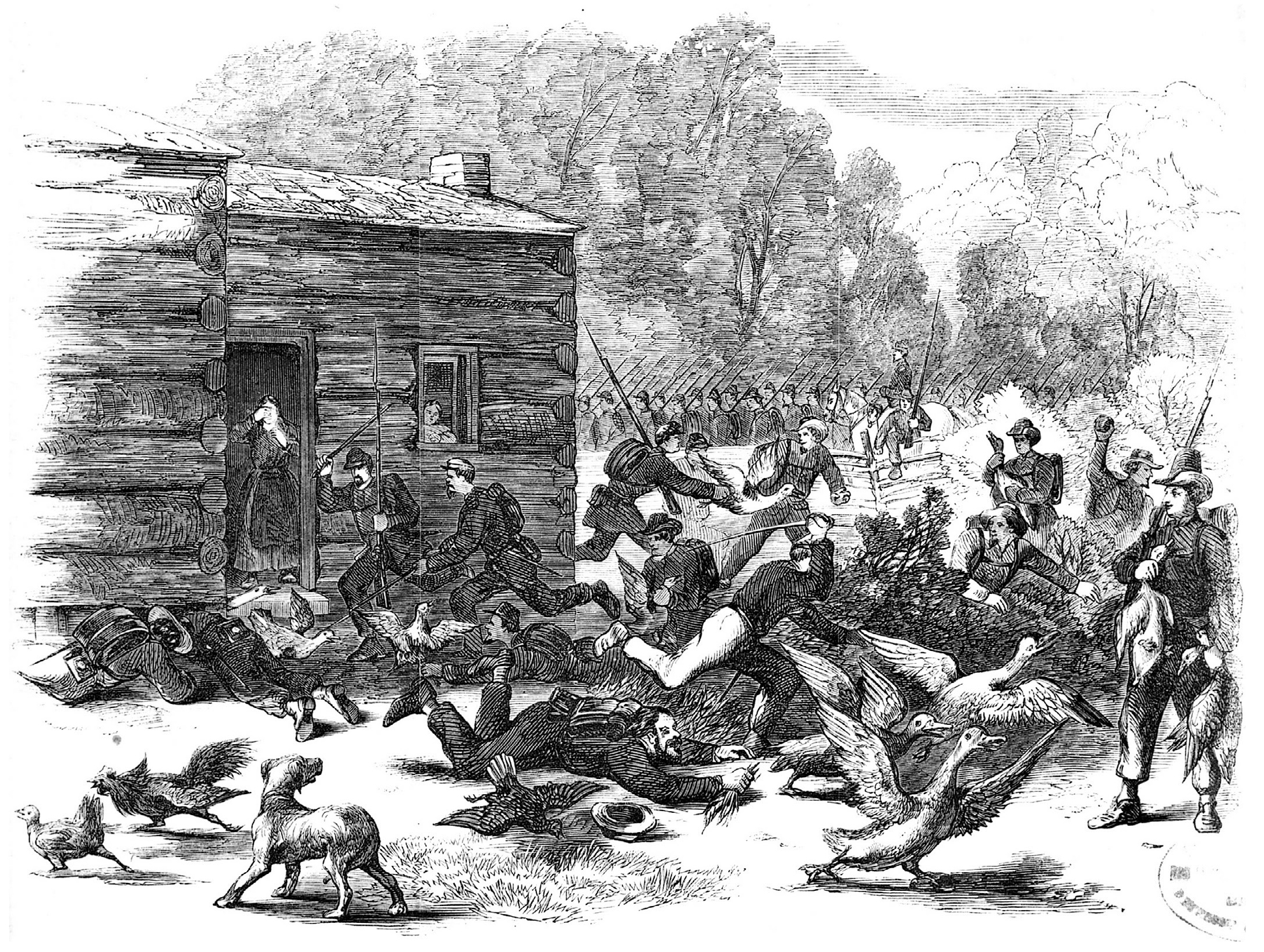

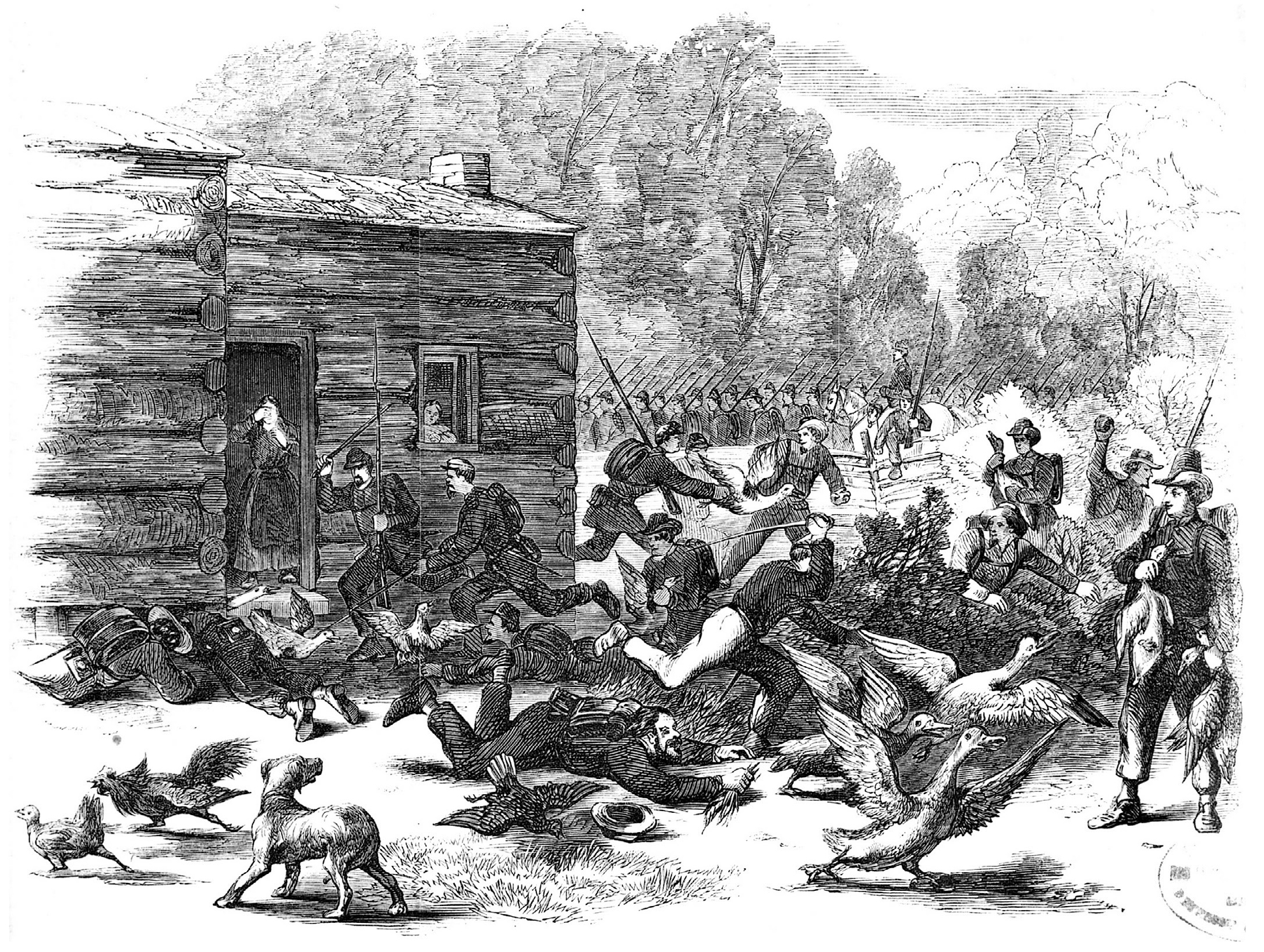

A war artist for Frank Leslies Illustrated Newspaper depicts invading Yankee soldiers plundering a Southern farm as they forage for food.

Library of Congress

Miss Eliza had reason to be afraid. Like most white Southerners, she would have known that the Confederacy was disintegrating and that Yankees were sweeping over the South. Frightening tales traveled from plantation to plantation, telling how Yankee soldiers were ransacking houses, turning the air thick with feathers as they ripped open mattresses and beds, searching for guns and silver and other valuables. How the Yankees swarmed over fields, stealing horses and hogs and chickens and molasses and flour, leaving little to eat. How the roads were littered with wasted carcasses of hogs and cattle. To Miss Eliza and other white Southerners, the Yankees were blue devils, determined to destroy the South, to starve out the Rebels and ruin their property, leaving them broken and destitute.

House slaves such as Mittie often overheard their masters and other white people holding political conversations and discussing the progress of the Civil War. Whatever news the slaves picked up about the Freedom War, as they called it, they were quick to pass on to others along the grapevine telegraph. The grapevine telegraph carried news, gossip, and rumors as it wound its way informally from person to person, plantation to plantation.

Some rumors were true. It was through the grapevine telegraph that many slaves had learned about the Emancipation Proclamation, which President Abraham Lincoln had signed two years earlier, on January 1, 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation decreed that all slaves in the eleven Rebel states and their territories were free. Two years later, in January 1865, as Northern victory became inevitable, Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment, a law that abolished slavery