Confessions

of an Ugly

Stepsister

GREGORY MAGUIRE

ILLUSTRATIONS BY BILL SANDERSON

For Andy Newman

CONTENTS

Cinderella, or, The Little Glass Slipper from Perraults Histories

If I could say to you, and make it stick,

A girl in a red hat, a woman in blue

Reading a letter, a lady weighing gold...

If I could say this to you so you saw,

And knew, and agreed that this is how it was

In a lost city across the sea of years,

I think we should be for one moment happy

In the great reckoning of those little rooms...

Howard Nemerov, Vermeer,

from Trying Conclusions:

Old and New Poems

Stories Painted

on Porcelain

H obbling home under a mackerel sky, I came upon a group of children. They were tossing their toys in the air, by turns telling a story and acting it too. A play about a pretty girl who was scorned by her two stepsisters. In distress, the child disguised herself to go to a ball. There, the great turnabout: She met a prince who adored her and romanced her. Her happiness eclipsed the plight of her stepsisters, whose ugliness was the cause of high merriment.

I listened without being observed, for the aged are often invisible to the young.

I thought: How like some ancient story this all sounds. Have these children overheard their grandparents revisiting some dusty gossip about me and my kin, and are the little ones turning it into a household tale of magic? Full of fanciful touches: glass slippers, a fairy godmother? Or are the children dressing themselves in some older gospel, which my family saga resembles only by accident?

In the lives of children, pumpkins can turn into coaches, mice and rats into human beings. When we grow up, we learn that its far more common for human beings to turn into rats.

Nothing in my childhood was charming. What fortune attended our lives was courtesy of jealousy, greed, and murder. And nothing in my childhood was charmed. Or not that I could see at the time. If magic was present, it moved under the skin of the world, beneath the ability of human eyes to catch sight of it.

Besides, what kind of magic is that, if it cant be seen?

Maybe all gap-toothed crones recognize themselves in children at play. Still, in our time we girls rarely cavorted in the streets! Not hoydens, we!more like grave novices at an abbey. I can conjure up a very apt proof. I can peer at it as if at a painting, through the rheumy apparatus of the mind...

... In a chamber, three girls, sisters of a sort, are bending over a crate. The lid has been set aside, and we are digging in the packing. The top layer is a scatter of pine boughs. Though theyve traveled so far, the needles still give off a spice of China, where the shipment originated. We hiss and recoilughh! Dung-colored bugs, from somewhere along the Silk Route, have nested and multiplied while the ship trundled northward across the high road of the sea.

But the bugs dont stop us. Were hoping to find bulbs for planting, for even we girls have caught the fever. Were eager for those oniony hearts that promise the tulip blossoms. Is this is the wrong crate? Under the needles, only a stack of heavy porcelain plates. Each one is wrapped in a coarse cloth, with more branches laid between. The top platethe first onehasnt survived the trip intact. It has shattered in three.

We each take a part. How children love the broken thing! And a puzzle is for the piecing together, especially for the young, who still believe it can be done.

Adult hands begin to remove the rest of the valuable Ming dinnerware, as if in our impatience for the bulbs we girls have shattered the top plate. We wander aside, into the daylightpaint the daylight of childhood a creamy flaxen colorthree girls at a window. The edges of the disk scrape chalkily as we join them. We think the picture on this plate tells a story, but its figures are obscure. Here the blue line is blurred, here it is sharp as a pigs bristle. Is this a story of two people, or three, or four? We study the full effect.

Were I a painter, able to preserve a day of my life in oils and light, this is the picture I would paint: three thoughtful girls with a broken plate. Each piece telling part of a story. In truth, we were ordinary children, no calmer than most. A moment later, we were probably squabbling, sulking over the missing flower bulbs. Noisy as the little ones I observed today. But let me remember what I choose. Put two of the girls in shadow, where they belong, and let light spill over the third. Our tulip, our Clara.

Clara was the prettiest child, but was her life the prettiest tale?

Caspar listens to my recital, but my quavery voice has learned to speak bravely too late to change the story. Let him make of it what he will. Caspar knows how to coax the alphabet out of an inky quill. He can commit my tale to paper if he wants. Words havent been my particular strength. What did I see all my life but pictures?and who ever taught the likes of me to write?

Now in these shriveled days, when light is not as full as it used to be, the luxury of imported china is long gone. We sip out of clay bowls, and when they crack we throw them on the back heap, to be buried by oak leaves. All green things brown. I hear the youthful story of our family played by children in the streets, and I come home muttering. Caspar reminds me that Clara, our Clara, our Cindergirl, is dead.

He says it to me kindly, requiring this old head to recall the now. But old heads are more supple at recalling the past.

There are one or two windows into those far-off days. You have seen themthe windows of canvas that painters work on so we can look through. Though I cant paint it, I can see it in my heart: a square of linen that can remember an afternoon of relative happiness. Creamy flaxen light, the blue and ivory of porcelain. Girls believing in the promise of blossoms.

It isnt much, but it still makes me catch my breath. Bless the artists who saved these things for us. Dont fault their memory or their choice of subject. Immortality is a chancy thing; it cannot be promised or earned. Perhaps it cannot even be identified for what it is. Indeed, were Cinderling to return from the dead, would she even recognize herself, in any portrait on a wall, in a figure painted on a plate, in any nursery game or fireside story?

I

THE OBSCURE CHILD

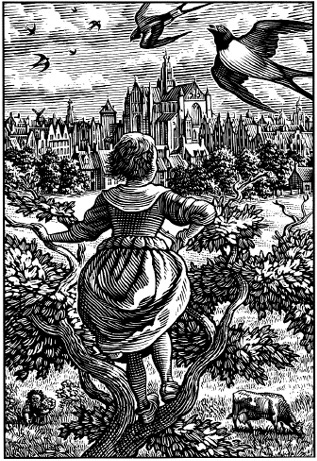

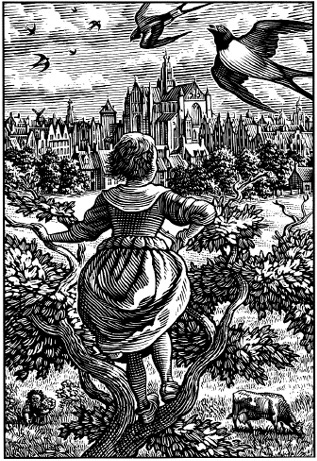

T he wind being fierce and the tides unobliging, the ship from Harwich has a slow time of it. Timbers creak, sails snap as the vessel lurches up the brown river to the quay. It arrives later than expected, the bright finish to a cloudy afternoon. The travelers clamber out, eager for water to freshen their mouths. Among them are a strict-stemmed woman and two daughters.

The woman is bad-tempered because shes terrified. The last of her coin has gone to pay the passage. For two days, only the charity of fellow travelers has kept her and her girls from hunger. If you can call it charitya hard crust of bread, a rind of old cheese to gnaw. And then brought back up as gorge, thanks to the heaving sea. The mother has had to turn her face from it. Shame has a dreadful smell.

So mother and daughters stumble, taking a moment to find their footing on the quay. The sun rolls westward, the light falls lengthwise, the foreigners step into their shadows. The street is splotched with puddles from an earlier cloudburst.