Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2013 by John Muller

All rights reserved

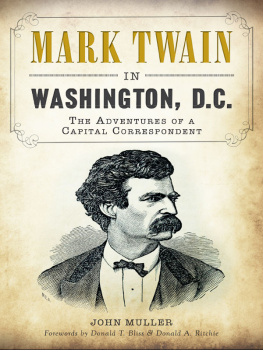

Front cover: Mark Twain in Cyclopedia of American Literature, vol. II (1875), 951. Authors collection.

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

ISBN 978.1.62584.031.8

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

print edition ISBN 978.1.60949.964.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Leeroy Beebopsmy brother, a captain in the United States Marine Corps and a man of several talents who, while grappling and running his way into local lore, never missed a deadline as a staff reporter for The Warrior and set down a combination of honesty and humor in Mullers Madness that lives on.

From left to right: B.A.M., Uncle G, Leeroy and Uncle Lil Wayne.

To my thinking, Shakespeare had no more idea that he was writing for posterity than Mark Twain has at the present time, and it sometimes amuses me to think how future Mark Twain scholars will puzzle over that gentlemans present hieroglyphics and occasionally eccentric expressions.

Charles Henry Webb, November 1865

Fame is a vapor; popularity an accident; the only earthly certainty is oblivion.

Mark Twain upon arriving in Washington, D.C., in the winter of 186768

Washington news-gatherers may claim precedence in the ranks of that great American guild known as The Press, for it is well established that metropolitan correspondents pursued their calling centuries before the discovery of the art of printing.

Ben Perley Poore, January 1874

Contents

Foreword

Mark Twain visited Washington, D.C., many times but never stayed long. As John Muller writes, he complained about the fickleness of Washingtons weather; it was tricky, changeable, unreliablelike its politics. As a teenage tourist, he wrote letters home for publication in his brothers local newspaper insightfully bemoaning how Congress failed to live up to the founders aspirations. As a thirty-three-year-old clerk to Nevada senator William Stewart, he was a quick study, mastering the intricacies of parliamentary maneuvers and how they were used for the legislators self-enrichment. Dismissed from his legislative post after a few weeks, he remained in town as a capital reporter and satirist, mocking legislative and bureaucratic self-importance, incompetence and corruption. In March 1868, he left Washington to launch his career as an author, taking with him a gold mine of anecdotes from the nations capital that would inspire his first novel (written with Hartford Courant editor Charles Dudley Warner). The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today is a thinly veiled documentary of the scandals of the Grant Administration, illustrating the corrupting influence of money in the legislative process. It reverberates with remarkable insight and relevance to the Washington of today.

As Twain became a celebrated author, public commentator and advocate for social justice and political reform, he returned to Washington often to hobnob with the powerful, lecture, testify before Congress, advise presidents and lobby. His fiction and public commentary were greatly influenced by his Washington experiences. His friendships with presidents and influential legislators seemed undiminished by his vitriolic assault on their policies, vacuous rhetoric and self-promotion. As good politicians, perhaps they feared the power of his pen and the enormous influence on public opinion of Americas first global celebrity.

Among the most quoted of public figures, Twains aphorisms are cited for almost any propositionoften inconsistent and contradictory positions. With a handy maxim for most any occasion, he is fondly quoted by conservatives and liberals, Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street activists, libertarians and union leaders. He is an equal-opportunity satirist whose wise commentary rings true today as he exposes human frailty in the abuse of power. A passionate believer in the potential of American democracy, he is deeply concerned about how Washington politics work in practice. As Twain said, It cannot be well or safe to let present political conditions continue indefinitely. They can be improved, and American citizenship should rise up from its disheartenment and see that this is done. Could anyone say it any better today?

Twains few months stay in Washington in 186768 was a turning point in his life. During a holiday trip to New York, he met his life partner, Livy Langdon, who would tame his frontier spirit and help discipline his inherent genius. He also received a letter from my great-grandfather, Elisha Bliss Jr., inviting him to write a book about his Quaker City tour of Europe and the Holy Lands, which launched Twains career as a popular author who became, as Atlantic Monthly editor William Dean Howells labeled him, the Lincoln of our Literature. Twain conceded that his bohemian life in Washington gave him his last days of unfettered freedom before he decided to pursue his craft with discipline and assimilate into progressive eastern society. Yet the lessons of his Washington experience greatly influenced his passion for justice and reform, expressed in his great novels, frequent lectures and political commentary.

Through his methodical research, John Muller has brought that critical time in Twains life alive, bringing the reader into the raucous environment in which the eccentric genius became an astute student of American democracy and its flaws and potential. We learn about life in the still raw and rugged capital city and the disparate characters who befriended the young writer. Unearthing neglected newspaper accounts and fresh insights from local archives, Muller fills an important gap in the abundant Twain scholarship by enhancing our understanding of influences that shaped this extraordinary American icon at the critical turning point in his career.

AMBASSADOR DONALD T. BLISS (RETIRED)

Washington, D.C.

Ambassador Donald Tiffany Bliss (Retired) spent thirteen years in the federal government and thirty years practicing law in Washington, D.C. The great-grandson and grandson of Mark Twains publishers, he wrote Mark Twains Tale of Today, an expertly guided tour for the reader who seeks a unified theory of Mark Twains politics, according to reviewer/scholar Kevin Mac Donnell. Bliss also wrote a play about Mark Twains last years, The Return of Halleys Comet, and co-authored Counsel for the Situation with the Honorable William T. Coleman Jr.

Foreword

Mark Twain blew in to Washington in November 1867 with a license to abuse and ridicule anyone and everybody he pleasedas well he did. He fit into the spirit of the eras Bohemian Brigade, the hard-drinking, irreverent and sardonic correspondents who had settled in the nations capital during the Civil War and stayed through the raucous years of Reconstruction. He wrote amusing pieces for a variety of papers, experimented with giving public lectures, triumphed as an after-dinner speaker, became private secretary to a senator and developed a well-deserved reputation for cantankerousness. He also caught the eye of the Washington ladies, who admired his snowy white vests, lavender gloves and amber-hued hair. He moved repeatedly from one boardinghouse to the next, protesting the shabby furniture and shabby food. That is Washington, he complained to his family. I mean to keep moving. After just a few months, he breezed out of town in March 1868 as abruptly as he had arrived. That he left in the middle of the presidents impeachment, the story of the year, proved that politics and journalism were only sideshows in his literary mind.

Next page

![Twain Mark - Autobiography of Mark Twain Vol. 1 / associate eds. Benjamin Griffin ... [et al.]](/uploads/posts/book/210276/thumbs/twain-mark-autobiography-of-mark-twain-vol-1.jpg)