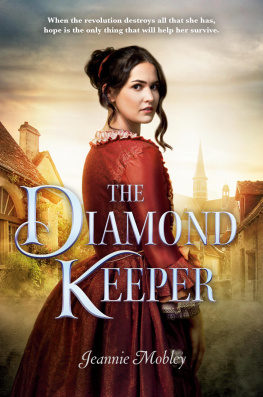

Copyright 2017 by Jeannette Mobley-Tanaka

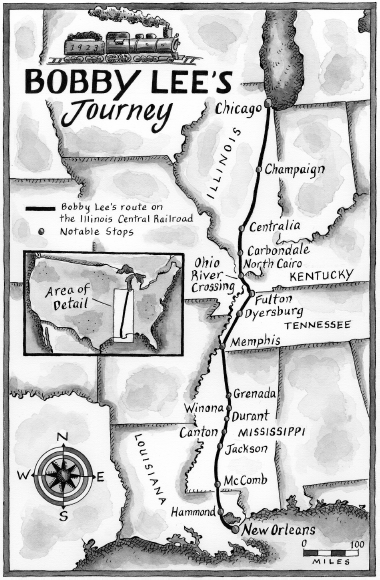

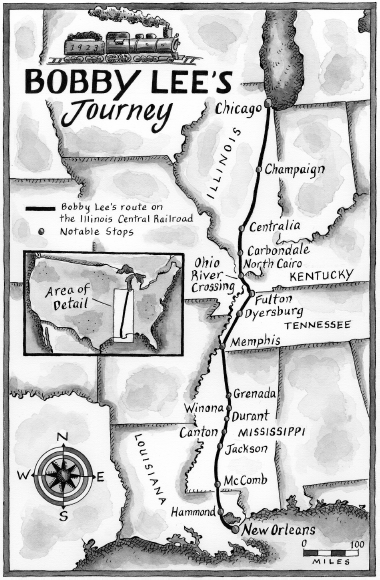

Map copyright 2017 by Jennifer Thermes

Interior art copyright 2017 by Oriol Vidal

All Rights Reserved

HOLIDAY HOUSE is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

www.holidayhouse.com

ISBN 978-0-8234-3894-5 (ebook)w

ISBN 978-0-8234-3895-2 (ebook)r

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mobley, Jeannie, author.

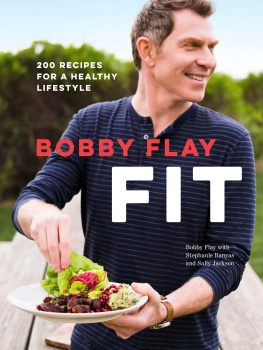

Title: Bobby Lee Claremont and the criminal element / Jeannie Mobley.

Description: First edition. | New York : Holiday House, [2017] | Summary:

In 1923, when New Orleans native and orphan Bobby Lee Claremont boards a train to Chicago, where he hopes to join the criminal element and make a new life for himself, far away from the heavy-handed salvation of the Sisters of Charitable Mercy, he acquaints himself with a group of intriguing and possibly dangerous passengers who cause Bobby Lee to reconsider his plans.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016051682 | ISBN 9780823437818 (hardcover)

Subjects: | CYAC: Railroad trainsFiction. | RunawaysFiction. |

OrphansFiction. | CriminalsFiction. | Mystery and detective stories.

Classification: LCC PZ7.M71275 Bo 2017 | DDC [Fic]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016051682

For Gregmy pride, my joy, my own little criminal element all grown up. I love you, man.

-1-

MAY 27, 1923

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA

7:45 A.M.

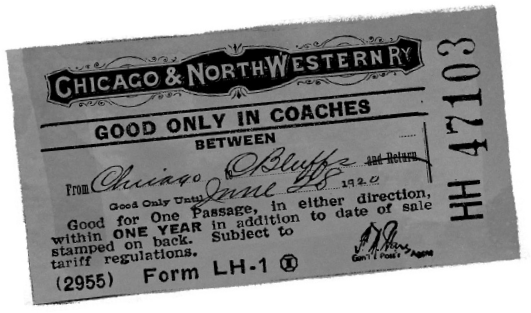

I shifted my weight from one foot to the other and glanced at the huge clock on the wall. According to the timetable below it, the train to Chicagoand freedomwould pull out of the station in fifteen minutes, whether I was on it or not. But that didnt make one measly bit of difference to the lady ahead of me at the ticket counter, who was rooting around in the bottom of her pocketbook for the remainder of her fare. The minute hand on the clock eased forward a tick as she picked out one penny after another, like she had all the time in the world. All the time and none of the sense, far as I could tell.

Imagine losing track of money! Id made plenty of mistakes in my life, but that sure wasnt one of them. I knew where every last cent of mine was: safe and sound inside my pocket. Excepting, of course, the two pennies I had placed on Mamans eyes when we laid her in the crypt. I could still see that bright copper against her alabaster face. It had been hard to give up two cents, but then again I figured I owed her that much, what with all I had cost her. Two pennies didnt make much difference to getting me out of New Orleans. And I had to get out of New Orleans.

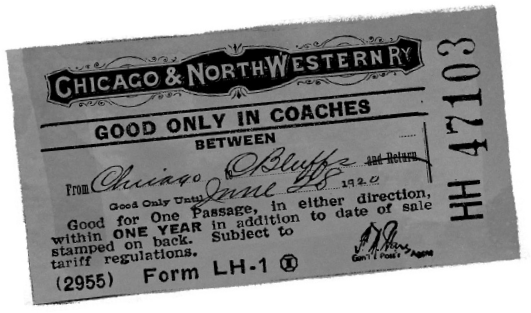

Thats why Id turned to the poor box of the Sisters of Charitable Mercy. I knew it was a sin to steallord knows, Sister Mary Magdalene had drummed that into my head often enoughbut the box had barely even been locked. And anyway, I reckoned it was a solid start on my new life of crime, which was about all I was good for. Thirteen years old, and I had already lied, cheated, and killed my mother, more or less. Stealing from a church was a nice addition to my rsum, seeing as how I was headed to Chicago to set myself up in a life of crime for good. Or at least I would be setting off, if the lady at the counter would get moving. If I could get my ticket and get on that train before either the Sisters or the police found the empty poor box and tracked me down.

At last, with a strange little Ooh! of satisfaction, the woman found her last penny, laid it on the counter, and scooted it under the barrier to the ticket master. He counted her money with painful deliberateness before sliding a ticket back to her. She snapped her pocketbook shut, straightened her hair and hat with one lace-gloved hand, picked up her ticket, picked up her carpetbag, double-checked the counter just in case she had forgotten any change, looked at the board to find her platform, and finally stepped out of the way.

I pressed forward to the counter and looked the ticket master square in the eyes, as if buying a train ticket to Chicago was old hat to me. Folks like me, aiming for a life of crime, know that confidence is the key to deception. Confidence, though, wasnt enough to hide the fact that I was only thirteenand a small thirteen at that, since the Sisters of Charitable Mercy hadnt been nearly as charitable as I would have liked when it came to their free lunches. The closest Id ever been to satisfied was that narrow space between not quite hungry and not quite full. Now, as the ticket master looked down at me, his blue eyes in their own narrow space between bushy eyebrows and half-moon spectacles, he wasnt all that satisfied neither. He watched me unfold the scrap of newspaper from my pocket and remove from it miscellaneous coins until I had the exact fare laid out on the counter.

You traveling to Chicago all by yourself? he said doubtfully.

Yes, sir. I got me a Yankee aunt up there, I lied. Another sin piled onto my mornings tally, but after a lifetime of sinning, topped off by robbing the poor box in a church, I figured God would hardly even notice. Plus, I needed the practice if I was going to be a criminal. I had to get to where my conscience hardly even noticed either, which wasnt going to be easy after all the hours Id spent in the company of Sister Mary Magdalene and all her long-winded charitable mercy. Id done plenty of lying, cheating, and stealing for as long as I could remember, but Id done plenty of penance too.

What about your momma and daddy? asked the ticket master. Aint they here to see you off?

Yes, sir, thats my daddy over yonder, I said, pointing to a stranger standing by himself near the door. This time, it might not have been a lie. Maman had never told me who my daddy was; maybe she hadnt known herself. In my case, it seemed even being born had been a sin.

He wants me to buy my own ticket, to prove Im old enough to travel alone. My aunt will meet me at the station in Chicago. I smiled and looked the ticket master in the eye again, willing him to hurry. Only six minutes until the train pulled out.

The ticket master scrutinized the stranger Id pointed out, and his eyebrows gradually slid back down to where they belonged. He counted out the money Id put on the counter with slow hands, moving like a winding-down clock. It was my time that was running outin more ways than one. When I had pointed out my daddy to the ticket master, I had noticed new arrivals entering the station. Four policemen in uniform, and I recognized one of them. He had helped return runaway orphans to the Sisters of Charitable Mercy so often that Sister Mary Magdalene called him by his Christian name. They had found the empty poor box. I had to get on that train before it left, and before they spotted me.