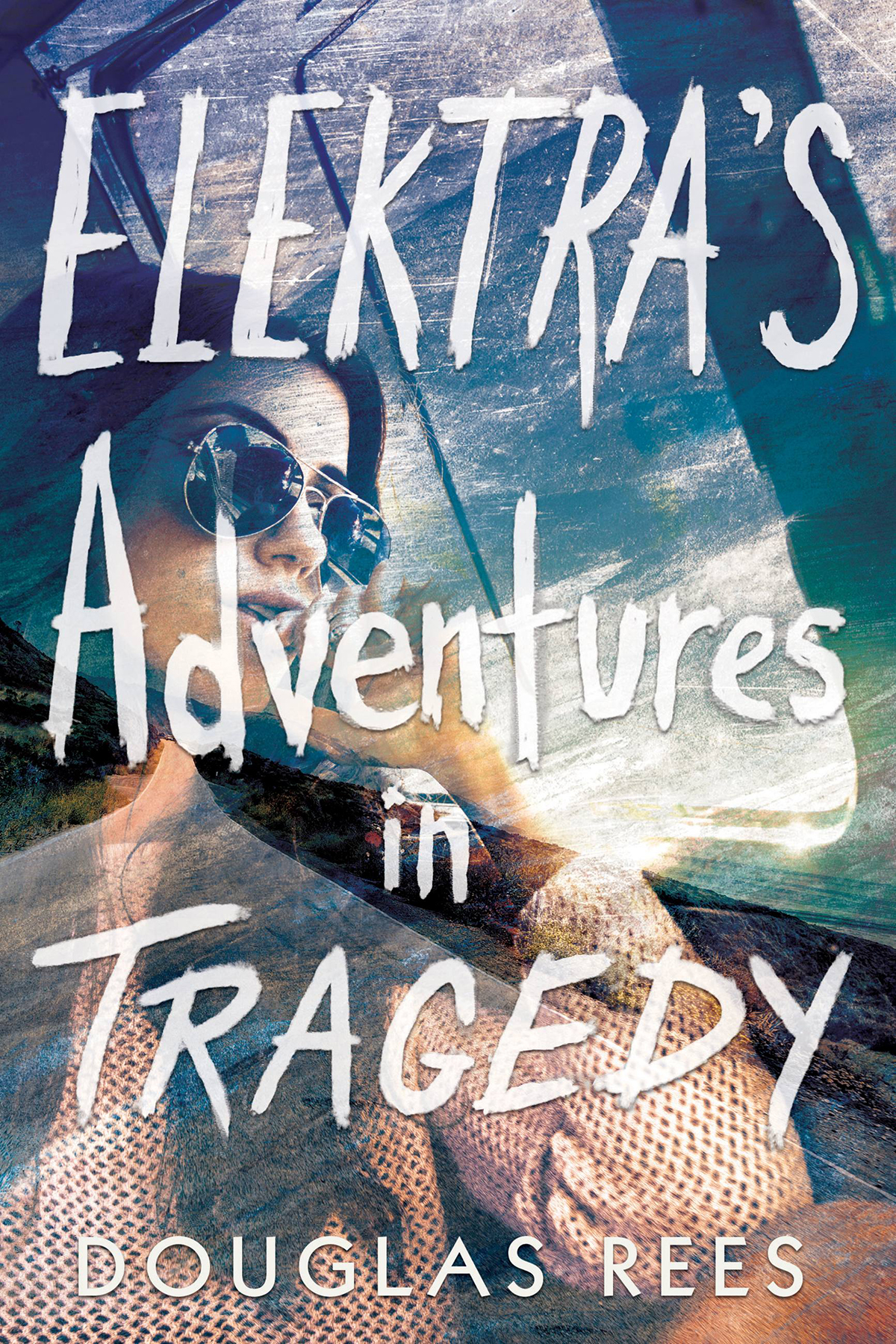

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com . Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Published by Running Press Teens, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Running Press Teens name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

We had been driving for four days when I decided to kill my mother. I had been considering it ever since we left Mississippi, and when I saw Guadalupe Slough for the first time, the only thing restraining me was that Thalia, my kid sister, was in the back seat. Id have had to kill her, too. And Thalia wasnt guilty of anything worse than trying to be cheerful.

But Guadalupe Slough overcame even her powers of denial.

Oh my God, Thalia said. Where are we, Mama?

It had been a long haul from Mississippi, with a lot of night driving, and a lot of fighting between Mama and me. Thalia had basically kept her mouth shut. Poor kidwedged into the back seat of Mamas ancient Volkswagen bug, Thalia hadnt made much more noise than the cardboard boxes and paper bags that filled the rest of the space. Less, actually. The boxes rattled.

But Mama and I had managed to fill the two thousand miles worth of silence with conversation. Pretty much the same conversation. It went something like this:

ME: Mama, this is crazy. Running away to California is not the answer. And besides, Im sixteen. Thats old enough to decide who I want to stay with, and I want to stay with Daddy. Turn around and take me home.

MAMA: Elektra, Im sorry you cant appreciate what Im doing for you. Im sorry you cant appreciate what an adventure this is, and Im desperately sorry that you cant appreciate the favor Im doing in rescuing you from Mississippi. But whether you can appreciate any of those things or not, theyre part of your life now, and youre going to have to accept them even if you dont want them. Trust me, in a year, youre going to thank me.

ME: I will never thank you for taking me away from everything Ive ever known.

MAMA: Thats part of the trouble: Mississippi is all youve ever known.

ME: Mississippi has everything that makes life worth living for me.

MAMA: You, young woman, were turning into a Southern belle. And I will not have a daughter of mine go down that road.

ME: I was not. And theres nothing wrong with being a belle. I want to go back home.

MAMA: No.

That was pretty much the essence of it, from the time we left home, all the way across Louisiana and into East Texas. By the time we got to West Texas, the conversation had been edited down a bit.

ME: Mama, this is kidnapping.

MAMA: You wish, Elektra.

ME: I want to go home. Take me back to Daddy now.

MAMA: Ive already explained to you about five hundred times why that isnt going to happen.

ME: You havent explained anything to me once. All you do is keep repeating that it is happening. And I want to know why.

MAMA: Ive explained it.

ME: No you havent.

By the time we were crossing Arizona, our discussion had been refined further.

ME: Mama, I want to go home now.

MAMA: Elektra, I dont give a damn what you want.

ME: That is so obvious.

And when we started the long, long drive north from Los Angeles, which was choked by traffic and smog, we had developed a sort of spoken shorthand.

ME: Mama

MAMA: Shut up.

All the while, Thalia in the back never said anything but an occasional Look at that.

She said it when we crossed Lake Pontchartrain, which was so big that when you were in the middle of the causeway, you couldnt see the shore youd come from or the shore you were going to. (Which, now that I think of it, summed up our situation perfectly.) She said it when we got lost in San Antonio and drove past the Alamo while trying to find our way back to Interstate 10. (It takes a kind of talent to lose an entire transcontinental highway. My mother has this talent.) She said it when we saw our first mesa in New Mexico, our first saguaro cactus in Arizona, and our first Joshua tree in the California desert.

Mama and I both knew why she was doing it; she was trying to make this trip seem like the adventure Mama wanted it to be. My poor baby sister was afflicted with the desire to make everything better, always. She had been trying to accomplish this transformation of life for her entire thirteen years. This would have been less of an impossibility for her if she had not been born into our family. My father is Nikos Kamenides, one of the greatest scholars of ancient Greek tragedy in the country. His wife, our mama, Helen, was an unpublished poet and novelist. I was a sixteen-year-old girl in a very bad mood. For all of us, life was tragedy. And right now we were living it out in a higher gear than usual.

I knew why Mama had left Daddy: because Daddy wouldnt leave Mississippi. He was the most outstanding scholar Cleburne College had, and they all knew it. He got privilege and respect like nobody else on campus. He could have gone to a bigger, more famous school, but there he would have been with a lot of other high-powered types like himself. At Cleburne, he was unique.

Mama wanted to be unique, too, but as the years went by and nothing happened with her writing, she started to blame it on Mississippi.

Ill never make it here, shed complain. I need to dwell in possibility. I need New York, or California. Hell, I need Minneapolis. Any place with people who are serious about writing. Hell, serious about anything worth being serious about. Painting, music, dance, for Gods sake. This place is going to kill me.

Emily Dickinson, whom you just abused by twisting her words, dwelled in possibility in the same house in the same town her whole life, Daddy would respond. So can you, if you want to. Were staying.

For JO

For JO