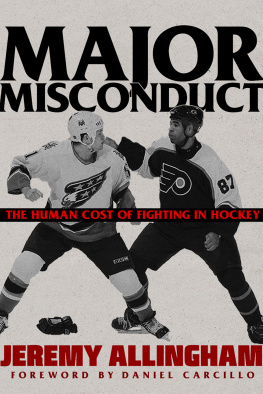

MAJOR MISCONDUCT

MAJOR MISCONDUCT

THE HUMAN COST OF FIGHTING IN HOCKEY

JEREMY ALLINGHAM

MAJOR MISCONDUCT

Copyright 2019 by Jeremy Allingham

Foreword copyright 2019 by Daniel Carcillo

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any part by any meansgraphic, electronic, or mechanicalwithout the prior written permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may use brief excerpts in a review, or in the case of photocopying in Canada, a licence from Access Copyright.

ARSENAL PULP PRESS

Suite 202 211 East Georgia St.

Vancouver, BC V6A 1Z6

Canada

arsenalpulp.com

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the British Columbia Arts Council for its publishing program, and the Government of Canada, and the Government of British Columbia (through the Book Publishing Tax Credit Program), for its publishing activities.

Arsenal Pulp Press acknowledges the xmkym (Musqueam), Swxw7mesh (Squamish), and slilwta (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations, speakers of Hulquminum/Halqemylem/hnqminm and custodians of the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territories where our office is located. We pay respect to their histories, traditions, and continuous living cultures and commit to accountability, respectful relations, and friendship.

The following interviews were developed for CBCs audio series Major Misconduct: Why We Let Kids Fight on Ice and are provided courtesy of the CBC: Ryan Diaz, Richard Doerksen, Eric Gottardi, Bruce Hamilton, Georges Laraque, John Ludvig, James McEwan 1, James McEwan 2, Riley McKay, Kaid Oliver, Stephen Peat 1, Stephen Peat 2, Walter Peat, Tim Preston, Jim Thomson, and Naznin Virji-Babul 1.

Cover and text design by Oliver McPartlin

Cover image: Mitchell Layton/National Hockey League via Getty Images

Edited by Shirarose Wilensky

Proofread by Alison Strobel

Printed and bound in Canada

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication:

Title: Major misconduct : the human cost of fighting in hockey / Jeremy Allingham.

Names: Allingham, Jeremy, 1982 author.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190125101 | Canadiana (ebook) 2019012511X | ISBN 9781551527710 (softcover) | ISBN 9781551527727 (HTML)

Subjects: LCSH: HockeyNorth America. | LCSH: Sports injuriesNorth AmericaPsychological aspects. | LCSH: Violence in sportsSocial aspectsNorth America. | LCSH: Hockey playersNorth AmericaBiography.

Classification: LCC GV847 .A45 2019 | DDC 796.962dc23

For James McEwan, Stephen Peat, and Dale Purinton. May the strength and courage it took to share these important stories make hockey a better, safer game.

CONTENTS

by Daniel Carcillo

FOREWORD

I LOVE the game of hockey! Like most kids growing up in small-town Canada (King City, Ontario), I began skating at the age of fouronce you can walk, you can skate. I was drawn to the game because of the speed, competition, physicality, and unity within the team structure. But from as early as I can remember, we were hitting each other on the ice. When I watched Hockey Night in Canada, famous commentators Don Cherry and Ron MacLean highlighted and honoured big hits and fights the most. Don Cherrys Rock Em Sock Em videos were a constant Christmas gift, showcasing the best goals, saves, and bloopers but placing the biggest emphasis on the hitting and the fighting. Looking back on my career and life, I can now see that I was trained from a young age to play the game of hockey with the goal of taking away my opponents will to play. You lean on your opponent through physical force, until they hesitate to go for the puck.

Because of Don Cherry and his videos, kids like me were sitting at home in front of the TV subconsciously absorbing a narrative that self-sacrifice for the good of the team is necessary for the group to succeed. That hate and rivalries are more important than scoring more goals than the other team. That fighting and physical contact are integral components of the sport of hockey.

My path to the National Hockey League (NHL) was not a conventional one. I didnt have any grandiose dreams of one day playing in the NHL. Rather, I was drawn to the game because it was an emotional release for me. Despite the sexual, physical, and verbal abuse I endured during my rookie season in the Ontario Hockey League, I was a thirty-goal scorer, and I had less than a handful of fights over three years. I was not an enforcer yet, but I played the game hard, and I was always the lead, or close, in hits per game. After I was drafted by the Pittsburgh Penguins in 2003, I knew that if I was going to be playing my brand of hockey against grown men, I would have to learn how to defend myself. You see, in hockey, you cannot deliver a clean hit on an opponent without someone else challenging you to a fight. So, in 200506, when I was old enough to turn pro and play in the American Hockey League, I gained twenty pounds of muscle in the off-season and began my mission to be the most complete hockey player I could be. And that included fighting.

My first professional fight was against Kevin Colley, a known enforcer and tough customer. I knocked him out. When I got back into the room during intermission, I remember my captain, Alain Nasreddine, looked at me and said, What the fuck was that?! I had been to three training camps with Alain, and he knew me as a hockey player, not an enforcer. But my thinking was this: If I can add enforcer to my resum, that will get me to the NHL quicker and help me stay around longer.

Little did I know I would eventually be pigeonholed into a role that would nearly kill me, and rob me of much of the joy of playing hockey at the professional level. I can now see how the subconscious messages I received as a child right through my teens about how to nobly play the game of hockey, combined with the abusive events of my rookie season, shaped me into the reckless, angry, and highly volatile hockey player who was willing to sacrifice himself for the good of the team. This mindset was both my best weapon and my biggest flaw.

Playing the enforcer role took its toll on me physically, mentally, and emotionally. I was nicknamed Car Bomb when I was in Philadelphia because of my unpredictable playing style. The fans loved it, but the anxiety I felt when looking at my opponents lineup during morning skate, knowing that a fight was coming, was difficult to deal with. I had to ignore those thoughts and feelings because they didnt serve me in the enforcer role, but that constant level of stress, and the way I was coping with it, were not sustainable.

By twenty-five, I was in a rehab facility for my dependence on opiates after undergoing two major surgeries in fourteen days. In rehab, I was introduced to spirituality, and it saved my life. It also changed the way I played the game, because I had healed past traumas and gotten to know myself on a deeper level. I knew what my faults were, what my triggers were, and what I needed to do to live a happier and more fulfilling life. I was less angry and emotional, and that equilibrium transferred onto the ice. I was a better teammate and began to fight less. I was lucky enough to go to the Stanley Cup Finals four times with three different teams in my last five seasons. I attribute that success to living the right way and being more aware and conscious of myself and others.

Next page