GENTLE AND FIERCE

Also by Vanessa Berry

Mirror Sydney

Ninety9

Strawberry Hills Forever

VANESSA BERRY

GENTLE AND FIERCE

Published 2021

from the Writing and Society Research Centre

at Western Sydney University

by the Giramondo Publishing Company

PO Box 752

Artarmon NSW 1570 Australia

www.giramondopublishing.com

Vanessa Berry 2021

Illustrations by Vanessa Berry

Designed by Jenny Grigg

Typeset by Andrew Davies

in Tiempos Regular 9/15pt

Printed and bound by Ligare Book Printers

Distributed in Australia by NewSouth Books

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia.

ISBN 978-1-925818-71-0

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Giramondo Publishing Company acknowledges the support of Western Sydney University in the implementation of its book publishing program.

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

Gentleness is a relationship to time that finds in the very pulsation of the present the feeling of a future and a past reconciled, that is, of a time that is not divided. This reconciled time makes life possible.

Anne Dufourmantelle, Power of Gentleness

Contents

Compound Eye

With this way of seeing I notice how animals have shaped my life. In my childhood my animals were the teddy bears that I believed might come to life when I wasnt looking, and the wise badgers or reckless toads of childrens books. I chased the silvery garden skinks that ran over rocks, imagining I could be quick enough to catch them. Then, as a teenager, I was drawn to the shadowy and the nocturnal. I wore dresses with black skirts like the wings of the bats that flew over at twilight, and felt an accord with the ravens that perched on the electricity wires, cawing long and low.

In my adult life my animals have been those that, like me, have the city as a home. There are the daily birds, the ibis and magpies and pigeons. There are the insects, the ants that course over the kitchen bench, the mosquitos that come to whine in my ear and keep me awake, and the spiders that startle me as they dart out across the walls of my room. There are the dogs that I have shared walks with, and the black cat that comes up to me whenever I sit in the garden, appearing in a blink, as if she has materialised from out of nowhere.

Through paying attention to animals and their constant presence comes a heightened awareness that we inhabit a shared world. Animals themselves, the objects that are made in their likenesses, and the ways humans describe animals and their lives, all form a part of it. With this comes an awareness of qualities, the descriptions for styles of behaviour which are used in definition of human and animal identities.

Gentleness and ferocity are two qualities which guide my experiences. Gentleness, with its quiet power, is a hidden strength. To be gentle is to resist the privileging of command above compassion. It is a quiet voice, a persistent whisper, calm and consoling. Ferocity is an armour, a forceful expression of resolve and protection. To be fierce is to know the intensity of the edges of feeling. It is the voice that calls out, intending to be heard. Gentleness and ferocity push and pull at each other, working together as life forces.

I recognise how gentleness and ferocity thread through the stories of my life, which are as much the stories of connections with others, human and non-human, as mine alone. Examining my experiences, turning them around and into new configurations, I envisage them radiating out into a web of life. Within this animals are always present, sometimes quiet, sometimes insistent, but always there.

Forces and connections can be observed within the smallest of objects, moments and encounters. By training ourselves to see this, by bringing attention to the details of our lives and giving voice to their extended stories, we can harness our energies, both gentle and fierce, towards care for the living world.

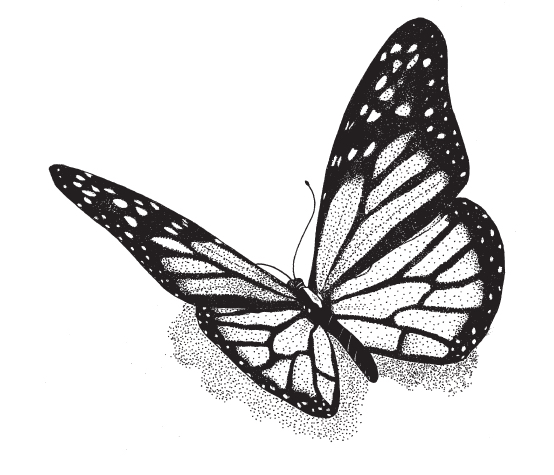

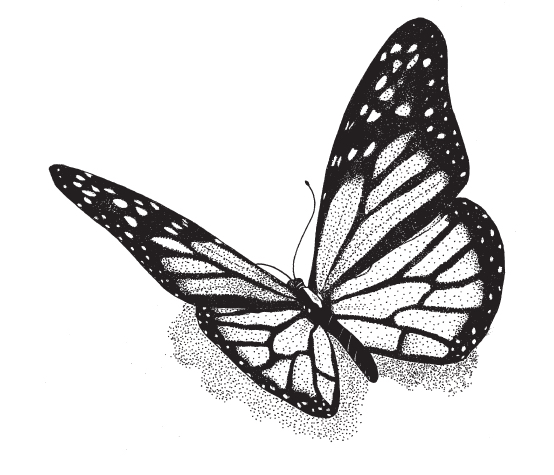

The Butterfly Effect

If names shape destinies, mine has in part been shaped by butterflies. At first I knew my name as a sound, three syllables finishing in a soft hiss before the stop of the a. I learned to write it, the double ss curling like caterpillars. When I consulted a book of names and their meanings, and found Vanessa to mean butterfly, this fact was a gift hidden inside my identity.

Before Vanessa came to mean butterfly it began as an endearment created by Jonathan Swift for his lover Esther Vanhomrigh. By switching the first syllables of her two names and running them together he composed a new name that was emblematic of their private world. They wrote passionate letters to each other, and although their romance was fraught with tension and uneven affections, Swift wrote a long poem, Cadenus and Vanessa, in their honour. The name Vanessa remained between them alone until after her death, when Cadenus and Vanessa was published. After this the name flew free. A century later it caught the attention of a Dutch entomologist who chose it for a genus of butterfly, the colourful species commonly known as admirals and painted ladies. It was in this way that the name Vanessa came to represent butterflies, and to flutter from name, to butterfly, and then to name again.

Sharing a name with an animal, as with any deliberate act of attention to something particular, attunes you to their presence. Vanessas flit past me with light movements of their bright wings and I see myself in them. I think of them in times when I am carried along by circumstances rather than my intentions, and let them guide me. Let go, I tell myself, surrender to the flow of things, like butterflies are carried by the wind, and scent and colour provide their direction.

As a child, to account for the shyness that saw me fit so poorly into social situations, I would console myself with the fact that I was part butterfly. They were my namesakes and with them I could drift. Any mention of butterflies was a story intended for me, and so Id go searching for them. On the bookshelf in the study were two tall stacks of National Geographic magazines. My parents had subscribed to it for decades and there was a complete set from the 1970s, their yellow spines listing the contents in intriguing combinations: Mount St Helens, Ancient Ashfall, Wildlife Refuges, Bulgaria, Giant Otters. It seemed there was no place or topic that wouldnt eventually come to the magazines encyclopaedic attention. I travelled across the maps of the stars or the ocean floor or into the photographs of cities and forests and people living their daily lives in Kunming or Veracruz. Later, as an adult, I realised the limitations of the magazines approach, and how many of the articles and photographs showed me ethnographic stereotypes, but as a child I found in them a way to imagine the wider world and its places, people and animals.

Next page