First published in 1893, 1894, by Rudyard Kipling

First Racehorse for Young Readers Edition 2016

Foreword copyright 2016 by Michael Patrick Hearn

Racehorse for Young Readers books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Racehorse for Young Readers is a pending trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

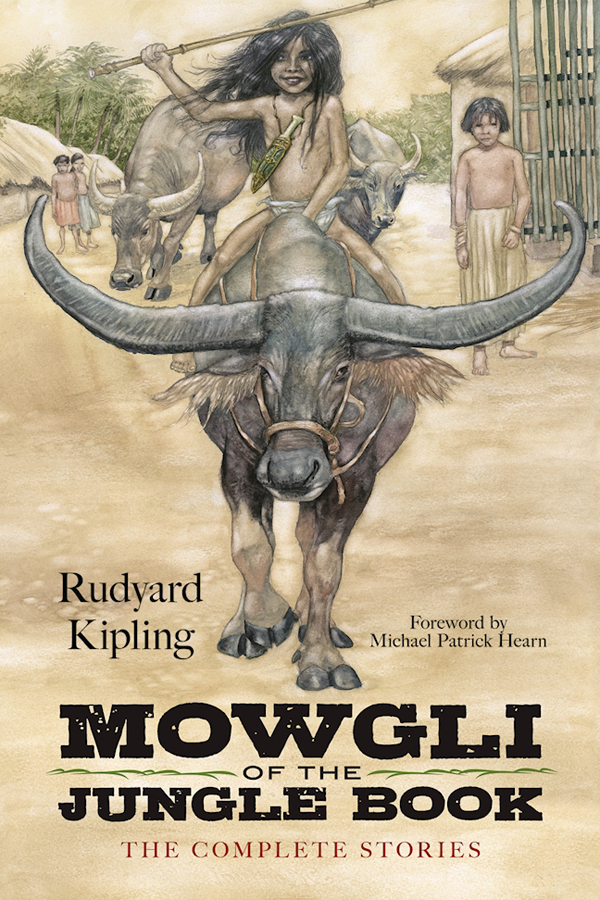

Cover artwork credit: ngel Domnguez

Print ISBN: 978-1-944686-32-1

eISBN: 978-1-944686-33-8

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

HOW TO SAY THE NAMES IN THIS BOOK

Akela A-kay-la .

Bagheera Bag-eera (same as an era in history).

Baloo Bar-loo .

Bandar-log Bunder-logue.

Buldeo Bul-doo .

Chil Cheel.

Dhole Dole.

Ferao Feer-ow.

Hathi Huttee.

Kaa Kar, with a sort of gasp in it.

Khanhiwara Karny-warra.

Messua Mes -war.

Mowgli Mow rhymes with cow .

Mysa Mi -sar.

Nathoo Nut-too .

Nilghai Neel-guy .

Phaona Fay-owna .

Raksha Rucksher .

Rama Rar-ma .

Sambhur Sarm-ber .

Seeonee See-oww-ee.

Shere Khan Sheer Kara,

Tabaqui Ta-b ar -kee.

Tha Thar.

Waingunga Wine-gunga .

Won-tolla Woon-toller.

FOREWORD

Thou art of the Jungle and not of the Jungle .

Bagheera the panther, Letting in the Jungle

The India that most Westerners know was largely the invention of one Englishman, Rudyard Kipling. The most famous of all Indian characters, Mowgli the Man-cub, was not created in India at all. He was not conceived even in England. Although born in Bombay in 1865, Joseph Rudyard Kipling was living comfortably with his new wife in Brattleboro, Vermont, when he seized the chance from editor Mary Mapes Dodge to contribute to St. Nicholas , then the most successful of all American juvenile magazines. He had already written a book about children, Wee Willie Winkie and Other Child Stories (1888). With his wife pregnant with their first child, it was now time to write one for them. Kipling himself had enjoyed reading St. Nicholas when he was a boy; and he was eager to write for this new young audience whom he considered (as he wrote Dodge): a People a good deal more important and discriminatinga peculiar People with the strongest views on what they like and dislike and I shall probably have to make three or four false starts before I can even get the key I hope to start on.

Kipling had been fond of animal stories when a lad himself, particularly the tales of Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox. I wonder if you could realize how Uncle Remus, his sayings, and the sayings of the noble beasties ran like wildfire through an English public school when I was about fifteen, he wrote Joel Chandler Harris on December 6, 1895. And six years ago in India, meeting an old schoolmate of those days, we found ourselves quoting whole pages of Uncle Remus that had got mixed in with the fabric of the old school life. At first, Kipling told Dodge that he was contemplating a series of Noahs Ark Tales. But quickly the stories switched to a place that he knew best: the India of his boyhood. In the stillness, and suspense, of the winter of 92, some memory of the Masonic Lions of my childhoods magazine, and a phrase in Haggards Nada the Lily , combined with the echo of this tale, he reported in his autobiography, Something of Myself (1937). He was vaguely recalling a tale about a lion-hunter in South Africa who fell among lions who were all Freemasons, and with them entered into a confederacy against some wicked baboons. This was James Greenwoods otherwise forgotten whimsical King Lion that was serialized in Boys Own Magazine (JanuaryDecember 1864).

Also, he had read recently H. Rider Haggards Nada the Lily (1892) in which a Zulu child was raised by wild dogs. It was a chance sentence of yours in Nada the Lily that started me off on a track that ended in my writing a lot of wolf stories, Kipling confessed to Rider Haggard in a letter of October 20, 1895. You remember in your tale where the wolves leaped up at the feet of a man sitting on a rock? Somewhere on that page I got the notion. Curious how things come back again, isnt it? As these ideas were percolating in his fertile brain, Kipling came up with another feral child for a short story for adults set in India, In the Ruhk, which he published in Many Inventions (1893).

Children raised in the wild were nothing new in literature or legend. Romulus and Remus, the twin brothers who supposedly founded the city of Rome, were said to have been suckled by a she-wolf. Mythic huntress Atalanta was weaned by a she-bear until hunters found and raised her in ancient Greece. Over the centuries there were numerous reports of actual children living with wolves, bears, cattle, sheep, and other creatures. The celebrated case of Dr. Jean Marc Gaspard Itard and Victor of Aveyron of the late eighteenth century formed the basis for Franois Truffauts famous 1970 French film, LEnfant Sauvage . Kipling could have been acquainted with William Henry Sleemans often-quoted pamphlet An Account of Wolves Nurturing Children in their Dens (1862). Doubtless many of these reports were frauds, but the legends lived on.

Kipling called his feral boy, a woodcutters abandoned son, Mowgli. A name I made up, he admitted. It is pronounced Mowglee (accent on the Mow ), adding later, Mow rhymes with cow . One of his characters says the name means frog, but even that was a fiction. It does not mean frog in any language I know of, Kipling later admitted. Only a secondary player in In the Ruhk, the young man Mowgli reveals his pedigree, explaining that the wolves following him are my playmates and my brothers, children of that mother that gave me suck. Children of the father that lay between me and the cold at the mouth of the cave when I was a little naked child. He happily acknowledges one wolf, now slavering at his knee, as his dear brother: Yes, when I was a little child he was a cub rolling with me on the clay.

Kipling admitted in a footnote to its republication in McClures (June 1896), that In the Ruhk was the first written of the Mowgli stories, though it deals with the closing chapters of his careernamely, his introduction to white men, his marriage, and civilization. Its point of view differs significantly from that of his childrens tales: here Mowgli is observed on the periphery rather than as the active protagonist at the center of the narrative. The grown Mowgli is not exactly the same character as described in The Jungle Books . He is introduced like a Punjabi Pan, some wandering wood-god playing upon a rude bamboo flute, to whose music four huge wolves danced solemnly on their hind legs. He inhabits two worlds but is not really native to either of them. I am without a village, he confesses. I am a man without caste, and for that matter, without a father. He becomes an outcast of both the jungle and the village. He does not know where he really belongs. He is the proverbial outsider.

Having discovered his theme, Kipling diligently went to work inventing the boys life prior to leaving the Jungle for good. After blocking out the main idea in my head, the pen took charge, and I watched it begin to write stories about Mowgli and animals, which later grew into the Jungle Books . Several are directly linked to In the Ruhk, enlarging on incidents just hinted at in the earlier story: Mowglis Brothers explains why the Man-cub hates tigers; Tiger-Tiger reveals why the villagers said that I was possessed of devils, and drove me from the village with sticks and stones; and The Spring Running describes the time when those of the jungle bade me go because I was a man. He recognized the incongruity of writing about India while living in Vermont. Where I live now, in America, he wrote to a young fan on November 28, 1895, we have a great many animals, but they are not Jungle-creatures. We have foxes, and now and then a bear kills a calf or a pig. It was not quite so easy to produce these stories as he disingenuously explained to the boy, Writing Jungle Books is rather difficult. I have to translate out of beast talk and jungle talk into easy English and as the beasts use portmanteau words like the ones Humpty-Dumpty said to Alice through the looking-glass, there is a great deal of translation to be done. He kept up the pretense of his having merely recorded the stories told to him back in India in his preface to the first Jungle Book . The adventures of Mowgli were collected at various times and in various places from a multitude of informants, most of whom desire to preserve the strictest anonymity, he insisted. Yet, at this distance, the editor feels at liberty to thank a Hindu gentleman of the old rock, an esteemed resident of the upper slopes of Jakko, for his convincing if somewhat caustic estimate of the national characteristics of his castethe Presbytes. Who this gentleman was, he never revealed. However, Presbytis is a genus of Old World monkey so he slyly implies that his source was an old white-bearded monkey. In truth the stories were almost entirely his own invention. Only The Kings Ankus unconsciously drew on the story of the robbers and the treasure from the ancient Jataka talesand likely the source for Chaucers Pardoners Tale. I dont remember when I didnt know the tale, Kipling replied to the accusation that he had stolen it from The Canterbury Tales . Got it I suppose from a fairy tale from my nurse in Bombay.