I thank God for my original Mowglis, India and Tia. For Mothers of Mowgli, Maa and Monmon. For Zoltan, for wisdom, for richer for poorer.

A little sleep, a little slumber, a little folding of the hands to rest, and poverty will come on you like a thief and scarcity like an armed man.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

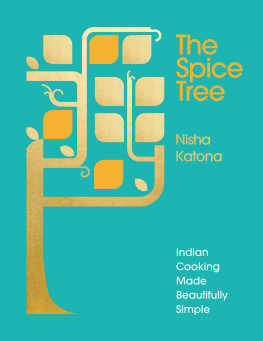

NISHA KATONA

M y life began in Ormskirk, Lancashire, where I was born, the daughter of Indian immigrant doctors. I remember growing up in a house in which every emotion was vociferously expressed, every guest embraced as a member of the family; a house filled with noise, with the aroma of wild exotic cooking and, above all, filled with so much love.

I was then raised in 1970s Skelmersdale a small town in West Lancashire where my parents took their first medical practice. This was an entirely white, working class area and it is not an unusual tale of the 1970s immigrant that some of my earliest memories were of being firebombed, of bricks being thrown through our windows and stones aimed at us on the way to school. We had little to offer. We were not cool. We were not rich. It was actually the thing that came most naturally to us that became our saviour it was our love for hospitality and our open kitchen that became the Kofi Annan of race relations. My mothers generous and gorgeous rolling buffet meant our little Skem home became the place for teens to hang out. Their parents followed and my dad strode through acres of Johnnie Walker Black Label on the swaying road to integration. He didnt complain, I promise you.

You see, above all, Indians love to feed people. There is something very humble and uncomplicated about Indian social culture we aim to please and we want you to like us. Warmth and generosity is beamed down on you like a blinding beacon of love, whether you want it or not. Taking you by the elbow to the kitchen table and setting before you enormous plates of food is the only way to make friends, right? Good hospitality is at the heart of the Indian home and guests are treated like royalty. If you arrived unannounced at my mothers home, within minutes the stove would be fired up and a delicious platter of something yellow and come-hither would be on its way to you. I remember scoffing snacks of tea-steeped chickpeas after school at brave Mr Jagotas shop one of the only Asian shops in Liverpool at the time while he shared stories of his own childhood. I recall the dinner table at home heaving with decidedly more dishes than there were people seated around it, everyone talking over each other and sharing out the food among ourselves.

So, although there may have been many, many already awkward teenage moments made all the more awkward by the mismatching hand-me-down knitwear, a kitchen full of excruciatingly different food, a distinct lack of Adidas and no shortage of brown corduroy, I am forever, truly and unapologetically grateful for my blushes, because without them, I may never have daydreamed Mowgli into existence.

FROM THE COURTROOM TO THE KITCHEN

My route to the kitchen is perhaps an unusual one. I didnt start off with a desire to work with food, although maybe on some deeper level I did. Like any good Indian daughter, I worked hard at school and passed all my exams. I then went on to become the first female Indian barrister in Liverpool. The law, especially at that time, was a very male-dominated industry and I recall on my first day of mini pupillage being sent a note by the head of chambers that said: Tell her not to return tomorrow as she is female and Asian and the bar is no place for such a person. I surprised myself by returning to chambers the next day. I was more afraid of my mother than of the man at the top of the stagnant ivory tower.

Determination and the knowledge that I would have to work ten times harder than those around me lead on to a thoroughly enjoyable legal career. I was then appointed trustee of the National Museums Liverpool by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport in 2008. And in 2009, the Cabinet Office anointed me Ambassador for Diversity in Public Appointments. I was an expert advisor for the Guardian; and I also spoke regularly on the radio both locally and nationally. I was proud to be giving a voice to women, hopefully at the same time demonstrating to other women that it is possible to succeed in a predominantly male work environment.

But a love of good food and an even greater love of the alchemy at play in the kitchen awoke in me the call to cooking; a call that I simply could not ignore. And as is so often the story with those of us who end up working in the food industry, those heady, bewitching scents of the kitchen kept pulling me back.

When not practising law, I lived the life of a fully fledged foodie. Holidays were booked solely around the local food offerings China, Vietnam, Morocco, Italy, South Korea and I became almost infatuated with sharing my new discoveries with anyone I could seat at my kitchen table for long enough. At night, I conjured up new dishes, marrying new discoveries with the long-held and well-learnt traditions from my familys own handwritten recipes. I became a curry evangelist, giving lessons in the ancient curry formulas of India.

It is obvious though, I think, that curry house offerings on most British high streets are unrecognisable to most Indians. Ask an Indian for a balti and they will bring you a bucket; tikka masala was born out of a Glaswegian mans love of gravy on his chicken; and passanda translates as I like, as in chicken, I like.

As I delved further, researched more, I kept asking myself, where was the authentic Indian home-cooking? The hugely varied, fresh, delicately spiced, healthy dishes enjoyed at lunch and dinner by Indian families around the world? British palates, at least until recently, seemed to be geared up to reject anything that did not involve chunks of meat floating in a neon sauce.

One reason for the lack of home-style cooking on the high street perhaps lies in the fact that traditional Indian cooking does not revolve around meat. In Britain, pulses used to be seen as mostly the preserve of hippies and those with gastrointestinal complaints. But Indian cooking is at its most magical in its cooking of vegetables, and what a varied, wonderful magic trick it is.

It felt time to share these ancient recipes; passed on by my ancestors, eaten at home, on the street, packed up and taken to work. To bring real Indian food to the masses. And so, although I had loved every single day of my 20 years at the Bar, and felt an enormous sense of pride in helping my clients the children and victims of neglect, abuse and domestic violence I couldnt escape those temptress tastes of far-flung lands any longer.